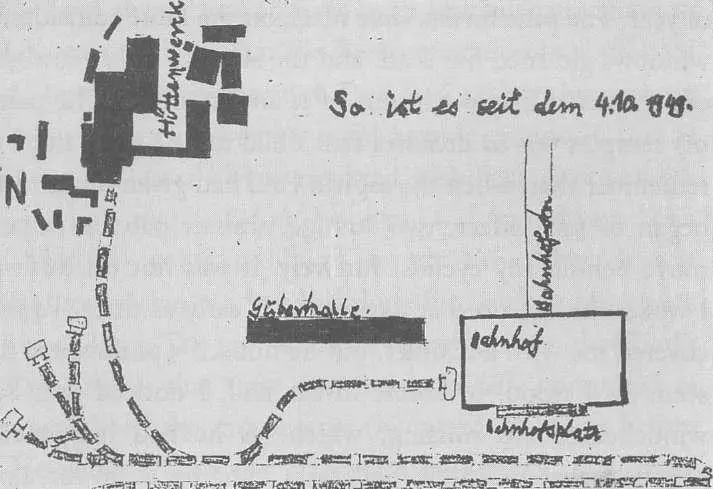

omeone dies of. Yes, it is very hard, said Mme Landau, one really doesn't know. All those years that he was here in Yverdon I had no notion that Paul had found his fate already systematically laid out for him in the railways, as it were. Only once, obliquely, did he talk about his passion for railways, more as one talks of a quaint interest that belongs to the past. On that occasion, said Mme Landau, Paul told me that as a child he had once spent his summer holidays in Lindau, and had watched from the shore every day as the trains trundled across from the mainland to the island and from the island to the mainland. The white clouds of steam in the blue air, the passengers waving from the windows, the reflection in the water — this spectacle, repeated at intervals, so absorbed him that he never once appeared on time at the dinner table all that holiday, a lapse that his aunt responded to with a shake of the head that grew more resigned every time, and his uncle with the comment that he would end up on the railways. When Paul told me this perfectly harmless holiday story, said Mme Landau, I could not possibly ascribe the importance to it that it now seems to have, though even then there was something about that last turn of phrase that made me uneasy. I suppose I did not immediately see the innocent meaning of Paul's uncle's expression, end up on the railways, and it struck me as darkly foreboding. The disquiet I experienced because of that momentary failure to see what was meant — I now sometimes feel that at that moment I beheld an image of death — lasted only a very short time, and passed over me like the shadow of a bird in flight.

My field of corn is but a crop of tears

I have barely any recollection of my own of Great-Uncle Adelwarth. As far as I can say with any certainty, I saw him only once, in the summer of 1951. That was when the Americans, Uncle Kasimir with Lina and Flossie, Aunt Fini with Theo and the little twins, and Aunt Theres, who was unmarried, came to stay with us in W for several weeks, either all together or one after the other. On one occasion during that time, the in-laws from Kempten and Lechbruck — emigrants, as is well known, tend to seek out their own kind — came to W for a few days, and it was at the resulting reunion of almost sixty members of the family that I saw my Great-Uncle Adelwarth, for the first (and, I believe, the last) time. Naturally, in the great upheaval caused by the visitors, in our own household and indeed throughout the whole village, since rooms had to be found elsewhere, he made no more impression on me at first than any of the others; but when he was called upon, as the eldest of the emigrants and their forefather, as it were, to address the gathered clan, that Sunday afternoon when we sat for coffee at the long trestle tables in the village hall, my attention was inevitably drawn to him as he rose and tapped his glass with a small spoon. Uncle Adelwarth was not particularly tall, but he was nonetheless a most distinguished presence who confirmed and enhanced the self-esteem of all who were there, as the general murmur of approval made clear — even though, as I, at the age of seven, immediately realized (in contrast to the adults, who were caught up in their own preconceptions), they seemed out-classed compared with this man. Although I do not remember what Uncle Adelwarth said in his rather formal address, I do recall being deeply impressed by the fact that his apparently effortless German was entirely free of any trace of our home dialect and that he used words and turns of phrase the meanings of which I could only guess at. After this, for me, truly memorable appearance, Uncle Adelwarth vanished from my sight for good when he left for Immenstadt on the mail bus the following day, and from there journeyed onward by rail to Switzerland. Not even in my thoughts did he remain present, and of his death two years later, let alone its circumstances, I knew nothing throughout my childhood, probably because the sudden end of Uncle Theo, who was felled by a stroke one morning while reading the paper, placed Aunt Fini and the twins in an extremely difficult situation, a turn of events which must have eclipsed the demise of an elderly relative who lived on his own. Moreover, Aunt Fini, whose closeness to him put her in the best position to tell us how things had been with Uncle Adelwarth, now found herself obliged (she wrote) to work night and day to see herself and the twins through, for which reason, understandably, she was the first to stop coming over from America for the summer months. Kasimir visited less and less often also, and only Aunt Theres came with any kind of regularity, for one thing because, being single, she was in by far the best position to do so, and for another because she was incurably homesick her whole life long. Three weeks after she arrived, on every visit, she would still be weeping with the joy of reunion, and three weeks before she left she would again be weeping with the pain of separation. If her stay with us was longer than six weeks, there would be a becalmed period in the middle that she would mostly fill with needlework; but if her stay was shorter there were times when one really did not know whether she was in tears because she was at home at long last or because she was already dreading having to leave again. Her last visit was a complete disaster. She wept in silence, at breakfast and at dinner, out walking in the fields or shopping for the Hummel figurines she doted on, doing crosswords or gazing out of the window. When we accompanied her to Munich, she sat streaming tears between us children in the back of Schreck the taxi driver's new Opel Kapitàn as the roadside trees sped past us in the light of dawn, from Kempten to Kaufbeuren and from Kaufbeuren to Buchloe; and later I watched from the spectators' terrace as she walked towards the silvery aeroplane, with her hatboxes, across the tarmac at Riem airport, sobbing repeatedly and drying her eyes with a handkerchief. Without looking back once, she went up the steps and vanished through the dark opening into the belly of the aircraft — for ever, as one might say. For a while her weeldy letters still reached us (invariably beginning: My dear ones at home, how are you? I am fine!) but then the correspondence, which had been kept up without fail for almost thirty years, broke off, as I noticed when the dollar bills that were regularly enclosed for me stopped coming. It was in the midst of carnival season that my mother put a death notice in the local paper, to the effect that our dear sister, sister-in-law and aunt had departed this life in New York following a short but bravely borne illness. All this prompted the talk again about Uncle Theo's far too early death, but not, as I well remember, of Uncle Adelwarth, who, like Theo, had died a few years or so before.

Our relatives' summer visits were probably the initial reason why I imagined, as I grew up, that I too would one day go to live in America. More important, though, to my dream of America was the different kind of everyday life displayed by the occupying forces stationed in our town. The local people found their moral conduct in general — to judge by comments sometimes whispered, sometimes spoken out loud — unbecoming in a victorious nation. They let the houses they had requisitioned go to ruin, put no window boxes on the balconies, and had wire-mesh fly screens in the windows instead of curtains. The womenfolk went about in trousers and dropped their lipstick-stained cigarette butts in the street, the men put their feet up on the table, the children left their bikes out in the garden overnight, and as for those negroes, no one knew what to make of them. It was precisely this kind of disparaging remark that strengthened my desire to see the one foreign country of which I had any idea at all. In the evenings, but particularly during the endless lessons at school, I pictured every detail of my future in America. This period of my imaginary Americanization, during which I crisscrossed the entire United States, now on horseback, now in a dark brown Oldsmobile, peaked between my sixteenth and seventeenth years in my attempt to perfect the mental and physical attitudes of a Hemingway hero, a venture in mimicry that was doomed to failure for various reasons that can easily be imagined. Subsequently my American dreams gradually faded away, and once they had reached vanishing point they were presently supplanted by an aversion to all things American. This aversion became so deeply rooted in me during my years as a student that soon nothing could have seemed more absurd to me than the idea that I might ever travel to America except under compulsion. Even so, I did eventually fly to Newark on the 2nd of January 1981. This change of heart was prompted by a photograph album of my mother's which had come into my hands a few months earlier and which contained pictures quite new to me of our relatives who had emigrated during the Weimar years. The longer I studied the photographs, the more urgently I sensed a growing need to learn more about the lives of the people in them. The photograph that follows here, for example, was taken in the Bronx

Читать дальше