Winfried Sebald - The Emigrants

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Winfried Sebald - The Emigrants» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, ISBN: 1997, Издательство: New Directions, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Emigrants

- Автор:

- Издательство:New Directions

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:978-0811213660

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Emigrants: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Emigrants»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

.

Published to enormous critical acclaim in the US,

has been acclaimed as "one of the best novels to appear since World War II" (

) and three times chosen as the 1996 International Book of the Year. The poignant and acclaimed novel about the beauty of lost things, while the protagonist traces the lives of four elderly German/Jewish exiles.

is composed of four long narratives which at first appear to be the straightforward accounts of the lives of several Jewish exiles in England, Austria, and America. The narrator literally follows their footsteps, studding each story with photographs and creating the impression that the reader is poring over a family album. But gradually, Sebald's prose, which combines documentary description with almost hallucinatory fiction, exerts a new magic, and the four stories merge into one. Illustrated throughout with enigmatic photographs.

The Emigrants — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Emigrants», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

On the afternoon that we arrived, the temperature plummeted. A snow blizzard set in that continued for the rest of the day and eased off to an even, calm snowfall only towards the night. When I went to the school in S for the first time the following morning, the snow lay so thick that I felt a kind of exhilaration at the sight of it. The class I joined was the third grade, which was taught by Paul Bereyter. There I stood, in my dark green pullover with the leaping stag on it, in front of fifty-one fellow pupils, all staring at me with the greatest possible curiosity, and, as if from a great distance, I heard Paul say that I had arrived at precisely the right moment, since he had been telling the story of the stag's leap only the day before, and now the image of the leaping stag, worked into the fabric of my pullover, could be copied onto the blackboard. He asked me to take off the pullover and take a seat in the back row beside Fritz Binswanger for the time being, while he, using my picture of a leaping stag, would show us how an image could be broken down into numerous tiny pieces — small crosses, squares or dots — or else assembled from these. In no time I was bent over my exercise book, beside Fritz, copying the leaping stag from the blackboard onto my grid-marked paper. Fritz too, who (as I soon learnt) was repeating his third grade year, was taking visible pains over his effort, yet his progress was infinitely slow. Even when those who had started late were long finished, he still had little more than a dozen crosses on his page. We exchanged silent glances, and I rapidly completed his fragmentary piece of work. From that day on, in the almost two years that we sat next to each other, I did most of his arithmetic, his writing and his drawing exercises. It was very easy to do, and to do seamlessly, as it were, chiefly because Fritz and I had the selfsame, incorrigibly sloppy handwriting (as Paul repeatedly observed, shaking his head), with the one difference that Fritz could not write quickly and I could not write slowly. Paul had no objection to our working together; indeed, to encourage us further he hung the case of cockchafers on the wall beside our desk. It had a deep frame and was half-filled with soil. In it, as well as a pair of cockchafers labelled Melolontha vulgaris in the old German hand, there were a clutch of eggs, a pupa and a larva, and, in the upper portion, cockchafers were hatching, flying, and eating the leaves of apple trees. That case, demonstrating the mysterious metamorphosis of the cockchafer, inspired Fritz and me in the late spring to an intensive study of the whole nature of cockchafers, including anatomical examination and culminating in the cooking and eating of a cockchafer stew. Fritz, in fact, who came from a large family of farm labourers at Schwarzenbach and, as far as was known, had never had a real father, took the liveliest interest in anything connected with food, its preparation, and the eating of it. Every day he would expatiate in great detail on the quality of the sandwiches I brought with me and shared with him, and on our way home from school we would always stop to look in the window of Turra's delicatessen, or to look at the display at Einsiedler's exotic fruit emporium, where the main attraction was a dark green trout aquarium with air bubbling up through the water. On one occasion when we had been standing for a long time outside Einsiedler's, from the shadowy interior of which a pleasant coolness wafted out that September noon, old Einsiedler himself appeared in the doorway and made each of us a present of a white butterpear. This constituted a veritable miracle, not only because the fruits were such splendid rarities but chiefly because Einsiedler was widely known to be of a choleric disposition, a man who despised nothing so much as serving the few customers he still had. It was while he was eating the white butterpear that Fritz confided to me that he planned to be a chef; and he did indeed become a chef, one who could be said without exaggeration to enjoy international renown. He perfected his culinary skills at the Grand Hotel Dolder in Zurich and the Victoria Jungfrau in Interlaken, and was subsequently as much in demand in New York as in Madrid or London. It was when he was in London that we met again, one April morning in 1984, in the reading room of the British Museum, where I was researching the history of Bering's Alaska expedition and Fritz was studying eighteenth-century French cookbooks. By chance we were sitting just one aisle apart, and when we both happened to look up from our work at the same moment we immediately recognized each other despite the quarter century that had passed. In the cafeteria we told each other the stories of our lives, and talked for a long time about Paul, of whom Fritz mainly recalled that he had never once seen him eat.

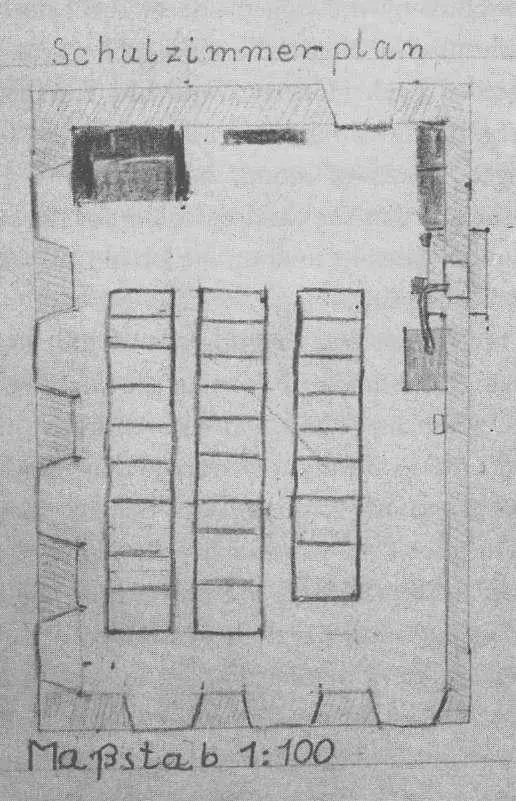

In our classroom, the plan of which we had to draw to scale in our exercise books, there were twenty-six desks screwed fast to the oiled floorboards.

From the raised teacher's desk, behind which the crucifix hung on the wall, one could look down on the pupils' heads, but I cannot remember Paul ever occupying that elevated position. If he was not at the blackboard or at the cracked oilcloth map of the world, he would walk down the rows of desks, or lean, arms folded, against the cupboard beside the green tiled stove. His favourite place, though, was by one of the south-facing windows let into deep bays in the wall. Outside those windows, from amidst the branches of the old apple orchard at Frey's distillery, starlings' nesting boxes on long wooden poles reached into the sky, which was bounded in the distance by the jagged line of the Lech valley Alps, white with snow for almost the entire school year. The teacher who preceded Paul, Hormayr, who had been feared for his pitiless regime and would have offenders kneel for hours on sharp-edged blocks of wood, had had the windows half whitewashed so that the children could not see out. The first thing Paul did when he took up the job in 1946 was to remove the whitewash, painstakingly scratching it away with a razor blade, a task which was, in truth, not urgent, since Paul was in any case in the habit of opening the windows wide, even when the weather was bad, indeed even in the harshest cold of winter, being firmly convinced that lack of oxygen impaired the capacity to think. What he liked most, then, was to stand in one of the window bays towards the head of the room, half facing the class and half turned to look out, his face at a slightly upturned angle with the sunlight glinting on his glasses; and from that position on the periphery he would talk across to us. In well-structured sentences, he spoke without any touch of dialect but with a slight impediment of speech or timbre, as if the sound were coming not from the larynx but from somewhere near the heart. This sometimes gave one the feeling that it was all being powered by clockwork inside him and Paul in his entirety was a mechanical human made of tin and other metal parts, and might be put out of operation for ever by the smallest functional hitch. He would run his left hand through his hair as he spoke, so that it stood on end, dramatically emphasizing what he said. Not infrequently he would also take out his handkerchief, and, in anger at what he considered (perhaps not unjustly) our wilful stupidity, bite on it. After bizarre turns of this kind he would always take off his glasses and stand unseeing and defenceless in the midst of the class, breathing on the lenses and polishing them with such assiduity that it seemed he was glad not to have to see us for a while.

Paul's teaching did include the curriculum then laid down for primary schools: the multiplication tables, basic arithmetic, German and Latin handwriting, nature study, the history and customs of our valley, singing, and what was known as physical education. Religious studies, however, were not taught by Paul himself; instead, once a week, we first had Catechist Meier (spelt e-i), who lisped, and then Beneficiary Meyer (spelt e-y), who spoke in a booming voice, to teach us the meaning of sin and confession, the creed, the church calendar, the seven deadly sins, and more of a similar kind. Paul, who was rumoured to be a free-thinker, something I long found incomprehensible, always contrived to avoid Meier-with-an-i or Meyer-with-a-y both at the beginning and at the end of their religion lessons, for there was plainly nothing he found quite so repellent as Catholic sanctimoniousness. And when he returned to the classroom after these lessons to find an Advent altar chalked on the blackboard in purple, or a red and yellow monstrance, or other such things, he would instantly rub out the offending works of art with a conspicuous vigour and thoroughness. Always before our religion lessons, Paul would always top up to the brim the holy water stoup, embellished with a flaming Sacred Heart, that was fixed by the door, using (I often saw him do it) the watering can with which he normally watered the geraniums. Because of this, the Beneficiary never managed to put the holy water bottle he always carried in his shiny black pigskin briefcase to use. He did not dare simply to tip out the water from the brimful stoup, and so, in his endeavour to account for the seemingly inexhaustible Sacred Heart, he was torn between his suspicion that systematic malice was involved and the intermittent hope that this was a sign from a Higher Place, perhaps indeed a miracle. Most assuredly, though, both the Beneficiary and the Catechist considered Paul a lost soul, for we were called upon more than once to pray for our teacher to convert to the true faith. Paul's aversion to the Church of Rome was far more than a mere question of principle, though; he genuinely had a horror of God's vicars and the mothball smell they gave off. He not only did not attend church on Sundays, but purposely left town, going as far as he could into the mountains, where he no longer heard the bells. If the weather was not good he would spend his Sunday mornings together with Colo the cobbler, who was a philosopher and a downright atheist who took the Lord's day, if he was not playing chess with Paul, as the occasion to work on pamphlets and tracts against the one True Church. Once (I now remember) I witnessed a moment when Paul's aversion to hypocrisy of any description won an incontestable victory over the forbearance with which he generally endured the intellectual infirmities of the world he lived in. In the class above me there was a pupil by the name of Ewald Reise who had fallen completely under the Catechist's influence and displayed a degree of oyerdone piety — it would not be unfair to say, ostentatiously — quite incredible in a ten-year-old. Even at this tender age, Ewald Reise already looked like a fully-fledged chaplain. He was the only boy in the whole school who wore a coat, complete with a purple scarf folded over at his chest and held in place with a large safety pin. Reise, whose head was never uncovered (even in the heat of summer he wore a straw hat or a light linen cap), struck Paul so powerfully as an example of the stupidity, both inbred and wilfully acquired, that he so detested, that one day when the boy forgot to doff his hat to him in the street Paul removed the hat for him, clipped his ear, and then replaced the hat on Reise's head with the rebuke that even a prospective chaplain should greet his teacher with politeness when they met.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Emigrants»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Emigrants» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Emigrants» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.