Winfried Sebald - Vertigo

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Winfried Sebald - Vertigo» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2001, ISBN: 2001, Издательство: New Directions, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Vertigo

- Автор:

- Издательство:New Directions

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- ISBN:978-0811214858

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Vertigo: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Vertigo»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Vertigo

The Emigrants

The Rings of Saturn

The New York Times Book Review

The Emigrants

Vertigo — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Vertigo», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

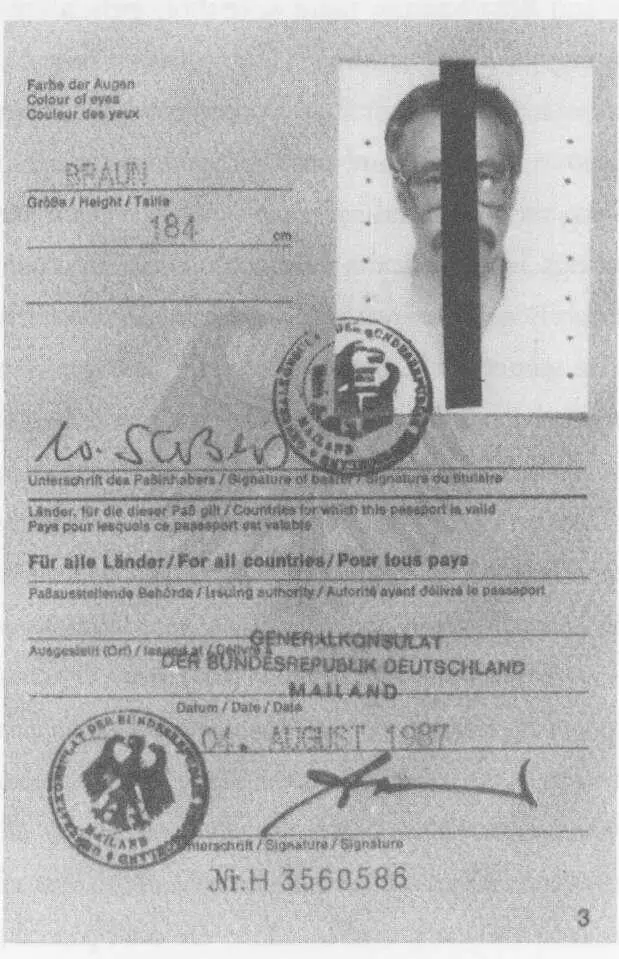

At nine next morning I was in the waiting room of the German consulate in the Via Solferino. At that early hour there were already a considerable number of travellers who had been robbed and people with other concerns, among them a family of artistes who seemed to me to belong to an era that ended at least half a century ago. The head of this small troupe — for that was undoubtedly what they were — was wearing a white summer suit and extremely elegant canvas shoes with a brown leather trim. In his hands he was twirling a broad-brimmed straw hat of exquisite form, now clockwise, now anticlockwise. From the precision of his movements one knew that preparing an omelette on the high-wire, that sensational trick performed by the legendary Blondel, would have been mere child's play for this grounded tightrope-walker whose true home, one felt, was the freedom of the air. Next to him sat a remarkably Nordic-looking young woman in a tailor-made suit, she too straight out of the 1930s. She sat quite still and bolt upright, her eyes shut the whole time. Not once did I see her glance up or notice the slightest twitch at the corners of her mouth. She held her head always in the same position and not a hair was out of place in her painstakingly crimped coiffure. With these two somnambulists, whose names proved to be Giorgio and Rosa Santini, there were three girls, all of about the same age, wearing summer frocks of the finest cambric, who resembled each other very closely. Now they would sit quietly, now wander about among the chairs and tables in the waiting room almost as if they were trying to make their meanderings into intricate, beautiful loops. One of them had a brightly coloured whirligig, one a collapsible telescope which she tended to hold to her eye the wrong way round, and the third a parasol. At times all three, with their sundry emblems, would sit at the window and gaze out at the Milanese morning, where the shimmering daylight was breaking through the heavy grey air. Sitting apart from the Santinis, though plainly with them, in her affections and by relation, was the nonna in a black silk dress. She was busy with crocheting and looked up only occasionally to cast what seemed to me a worried look at the silent couple or the three sisters. Although it took a long while until my identity had been established, by several phone calls to the relevant authorities in Germany and London, the time passed lightly in the company of these people. At length, a short, not to say dwarfish consular official settled himself on a sort of bar-stool behind an enormous typing machine in order to enter in dotted letters the details I had given concerning my person into a new passport. Emerging from the consulate building

with this newly issued proof of my freedom to come and go as I pleased in my pocket, I decided to take a stroll around the streets of Milan for an hour or so before travelling on, although of course I might have known that any idea of the kind, in a city so filled with the most appalling traffic, will end in aimless wandering and bouts of distress. On that day, the 4th of August, 1987,1 walked down the Via Moscova, past San Angelo, through the Giardini Pubblici, along the Via Palestro, the Via Marina, the Via Senato, the Via della Spiga, the Via Gesù, into the Via Monte Napoleone and the Via Alessandro Manzoni, by way of which I finally reached the Piazza della Scala, from where I crossed to the cathedral square. Inside the cathedral I sat down for a while, untied my shoe-laces, and, as I still remember with undiminished clarity, all of a sudden no longer had any knowledge of where I was. Despite a great effort to account for the last few days and how I had come to be in this place, I was unable even to determine whether I was in the land of the living or already in another place. Nor did this lapse of memory improve in the slightest after I climbed to the topmost gallery of the cathedral and from there, beset by recurring fits of vertigo, gazed out upon the dusky, hazy panorama of a city now altogether alien to me. Where the word "Milan" ought to have appeared in my mind there was nothing but a painful, inane reflex. A menacing reflection of the darkness spreading within me loomed up in the west where an immense bank of cloud covered half the sky and cast its shadow on the seemingly endless sea of houses. A stiff wind came up, and I had to brace myself so that I could look down to where the people were crossing the piazza, their bodies inclined forwards at an odd angle, as though they were hastening towards their doom — a spectacle which brought back to me an epitaph I had seen years before on a tombstone in the Piedmont. And as I remembered the words Se il vento s'alza, Correte, Correte! Se il vento s'alza, non v'arrestate! so I knew, in that instant, that the figures hurrying over the cobbles below were none other than the men and women of Milan.

That evening I was on my way to Verona once again. The train raced through the dark countryside at an alarming speed. This time I alighted at my destination without a second thought and, once I had had a double Fernet in the station bar and browsed through the Verona newspapers, I took a taxi to the Golden Dove, where, contrary to all expectation, at the height of the season, a room perfectly suited to my needs was made available and where I was treated with exquisite courtesy, both by the porter, who reminded me of Ferdinand Bruckner, and by the hotel manageress, who seemed to be waiting in the foyer for the express purpose of welcoming me as a long expected guest of honour who had finally arrived. Rather than asking for my passport, she simply handed me the register, and I entered my name as Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer, historian, of Landeck, Tyrol. The porter picked up my bag and preceded me to the room, where I gave him a tip that far exceeded my means, at which he left with a deep bow. That night under the roof of the Golden Dove, I felt safe as if under the wing of a bird whose plumage I saw in the finest shades of brown and brick-red, a well-nigh miraculous reprieve, as was the breakfast next morning, which I recall as a very dignified occasion. Confidently, as if from now on I could not put a foot wrong, I set off shortly before ten through the city streets, and soon found myself outside the Biblioteca Civica, where I proposed to spend the day working. A notice on the main entrance advised the public that the library was closed during the holiday period, but the door stood ajar. Inside, it was so gloomy that at first I had to feel my way forwards. In vain I tried a number of door handles, all of which seemed curiously high to me, before at last I found one of the librarians in a reading room flooded with the mild light of the early morning. He was an old gentleman with carefully trimmed hair and beard, who had just settled down to the days task behind his desk. He wore black satin armlets and gold-rimmed half-moon spectacles, and was ruling lines on one sheet of paper after another. Once he had prepared a batch, he looked up from the business in hand and enquired what it was I had come for. Having listened to my protracted explanation, he went to fetch what I wanted and before long I was sitting near one of the windows leafing through the folio volumes in which the Verona newspapers dating from August and September 1913 were bound. The edges were by now so brittle that the pages needed to be turned with much care. All manner of silent movie scenes began to be enacted before my eyes. In Via Alberto Mario I beheld divers gentlemen walking up and down and, at the very moment they supposed themselves unobserved, deftly side-stepping, with lightning alacrity, into the doorway of the building that housed the establishment of Dr Ringger, graduate of the medical schools of Paris and Vienna. Each of the many chambers within was

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Vertigo»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Vertigo» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Vertigo» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.