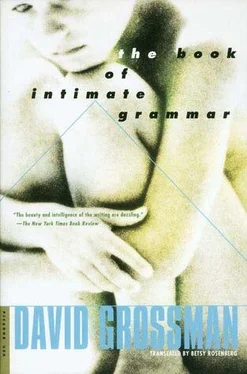

Even though the big event was still a year and a half away, Mama and Papa were up to their ears in arrangements. They were planning agrandiose affair, said Mama, they would rent the Empyrean Hall and hire an expensive photographer from Photo Gwirtz this time instead of using old Uncle Shimmik, whose hands trembled so badly at the last family affair that Mama came out looking hideous. Yochi’s bat mitzvah party had been celebrated modestly at home, and now she flew into a jealous rage. On me you scrimp, she exploded, and Mama replied, with a hint of malice, that a bar mitzvah is different, like it or not. Don’t worry, we’ll make it up to you with your wedding, only first let’s see the suitors, ha ha ha.

At night when Aron got up for a drink, he would find his parents huddled together over the big bar mitzvah ledger on the kitchen table. Cast aside were the Sick Fund stampbooks — who had time for them nowadays — the reddish-yellow stamps were glued on any which way, while the ledger was carefully bound in green shelf paper with a label on the cover: ARON’S BAR MITZVAH. Here his parents entered the menu of every bar mitzvah they attended, reckoned the costs, counted courses, criticized and compared the cuisine. In a year and a half the mortgage would be paid up, and they would take out a little loan, which, together with what they’d managed to put by already, would be enough to throw him such a bar mitzvah party, Mama clasped him to her bosom, “Their eyes will pop!”

Now she appeared on the balcony, searching high and low, her nostrils flaring. Papa yanked Aron back into the tree as stealthily as a guerrilla fighter, till both of them were safely hidden from her scrutiny. All Aron could see now through the leaves were her fingers turning white on the balcony railing.

“Moshe!” she shrieked, “how long do you intend to stay up there wiping snot?” A hush fell over the building. The tinkling of the piano died away.

Papa tucked his neck between his shoulders, then pushed it out again, thick and red, with a throbbing blue vein. Aron cringed. He had never seen Papa like this before, but Papa controlled himself, clenched his powerful jaws, and gravely, deliberately, began to smear the ointment on the sores. Mama waited, and then suddenly pounded on the railing: “A-ron!”—the sound waves encircled him like iron rings around a pole—“come home this instant to try on your boots!”

“What? But it’s summer!” he whispered to Papa.

Papa nodded. His eyes still intimated danger, but his chin dredgedup an old excuse: “That’s Mama for you, she likes to have things ready in advance,” he whispered. “Suppose we have to buy you a new pair of boots this year?”

But of course they would have to, the old pair was two years old, all worn out, with cracks in the soles. He definitely needed a new pair of boots: he and Gideon and Zacky were planning to open a tadpole farm, they were going to sell frogs to Bonaparte’s, the first French restaurant in Jerusalem.

“What is it,” whispered Papa. “Why the long face?”

Aron turned away so Papa wouldn’t see him. “Why does she have to talk to me like that,” he grumbled.

“Don’t take it to heart, Aronchik, your mama loves you. She worries, that’s why she talks like that.”

“I’m as tall as Gideon, I’m as tall as most of the kids in my class.”

“She wants you to be the best in everything, that’s all. A mother is a mother.”

“She hurt my feelings.”

Papa stroked his head. Aron melted at the touch. Again the piano tinkled upstairs, tentative, wary, like the first green sprouts after a forest fire. Papa sat still. Only his hand moved, stroking Aron. There was still enough light to see the veins on the leaves. The music fluttered through them, plucking delicate strings. Aron peeked up at the sky, the deep blue sky of twilight. And then Papa stared into his eyes until he made him smile.

“Anyway,” said Papa, “what’s-his-name, Napoleon, he was a shorty, and so was Zioma Schwatznicker, now that’s a fact!”

Aron found Mama in the kitchen, wobbling on the Franzousky with her head in the storage loft. Hearing him enter, she popped out again wearing a pink rubber bathing cap to protect her from the dust. Don’t think I didn’t see you in the tree, that we’ll settle later, now go get a pair of woolen socks from the sock drawer in the big closet. Woolen socks? grumbled Aron. Now? In the middle of summer? How do you expect to try on boots, then? Barefoot? But in this heat, Mama, wool? I know what I’m doing, now go get the socks.

Aron found Mama in the kitchen, wobbling on the Franzousky with her head in the storage loft. Hearing him enter, she popped out again wearing a pink rubber bathing cap to protect her from the dust. Don’t think I didn’t see you in the tree, that we’ll settle later, now go get a pair of woolen socks from the sock drawer in the big closet. Woolen socks? grumbled Aron. Now? In the middle of summer? How do you expect to try on boots, then? Barefoot? But in this heat, Mama, wool? I know what I’m doing, now go get the socks.

Angrily he opened the closet in his parents’ bedroom. Behind the sock drawer he found a little brown envelope, like the kind that came in the mail with Papa’s reserve orders, only this one had no name or address on it. Printed across the envelope were the words Alfonso’s Pussy Circus . He peeked inside and saw something strange, a black-and-white photograph on the back of a playing card. He knew at a glance this was something he shouldn’t be looking at. But when he peeked again, his hands began to tremble. Close the door and get out, he commanded himself. Close the door and get out, he whispered to save his soul, then slipped the card into the envelope and put it back, trembling so much he almost dropped the socks. He stood frozen in the middle of the bedroom. What was I looking for? And again he commanded, with a quivering voice, Get out of here now! I said now! Then he stumbled to his room and flopped down on the bed, to calm himself before Mama found the boots in the storage loft. He curled up in a ball and suddenlyrealized that things had not been going at all well lately. There were certain signs, like the broken guitar strings or the fights with Zacky, though what did they prove, what did they mean, he only knew that up until now, it might have been possible to turn back the wheel of signs and proofs. He didn’t think, he only tried to listen to the sober voice inside him whisper: “Not good,” and “Tsk tsk tsk,” like a doctor’s prognosis, and Aron was startled, not by the voice, but by the gravity of the “Tsk tsk tsk” and the shake of the head that accompanied it, like Mama’s that time they passed a fatal road accident on the bus to Tel Aviv, and suddenly he recoiled at the thought. Nothing’s changed, he told himself, it’s just a mood, get up, but he didn’t.

The day was over; a lazy summer evening stretched ahead. From every doorway came smells of salad finely chopped, dewy cucumbers in yogurt, herring wreathed with onion, eggs dancing sunny side up, fresh rye bread thickly sliced and ready on the table. The sultry sky began to darken at the seams. Blithe new strains floated through the fourth-floor window — hesitant at first, measured and slow, then breaking loose in a rampage of pounding. Papa sighed and collected his tools from the fig tree. He looked down at his fingers, stained yellow with the ointment, as he listened to the music, wrinkling his brow in an effort to remember where he’d heard it before. He shrugged his shoulders. Hinda’s voice boomed out, she’d found the boots and was calling Aron to try them on. Just as he jumped down from the fig tree, Zacky rode over. “You mean to say you’ve been up there alone the whole time?” He scowled in innocent dismay. “Go on home now, it’s getting dark,” said Papa, and Zacky stared down at his bicycle fender and said he didn’t feel like going home yet. But it’s dangerous to ride around without a light, Zachary; Don’t have one — dynamo’s out. Remind me tomorrow and I’ll fix it for you: never fear — Moishe’s here. And Papa scratched his prickly hair, but his mind was elsewhere, his hand perfunctory, and Zacky drew back with indignation and quickly rode away, pouting as he leaned over the handlebars. Oh, please let a car speed by with blinding headlights, like a fist out of the blue. Around the corner he slowed to a stop, looked both ways, and kicked the taillight of the Fiat with all his might.

Читать дальше

Aron found Mama in the kitchen, wobbling on the Franzousky with her head in the storage loft. Hearing him enter, she popped out again wearing a pink rubber bathing cap to protect her from the dust. Don’t think I didn’t see you in the tree, that we’ll settle later, now go get a pair of woolen socks from the sock drawer in the big closet. Woolen socks? grumbled Aron. Now? In the middle of summer? How do you expect to try on boots, then? Barefoot? But in this heat, Mama, wool? I know what I’m doing, now go get the socks.

Aron found Mama in the kitchen, wobbling on the Franzousky with her head in the storage loft. Hearing him enter, she popped out again wearing a pink rubber bathing cap to protect her from the dust. Don’t think I didn’t see you in the tree, that we’ll settle later, now go get a pair of woolen socks from the sock drawer in the big closet. Woolen socks? grumbled Aron. Now? In the middle of summer? How do you expect to try on boots, then? Barefoot? But in this heat, Mama, wool? I know what I’m doing, now go get the socks.