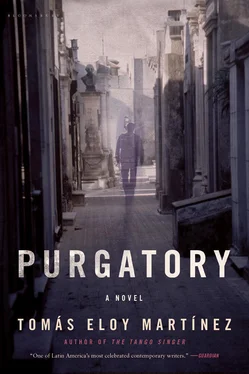

Tomás Eloy Martínez - Purgatory

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tomás Eloy Martínez - Purgatory» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Publishing PLC, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purgatory

- Автор:

- Издательство:Publishing PLC

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purgatory: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purgatory»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

"Purgatory" narrates the anxiety of the love lost and then found in a magnificent reconstruction of the sinister events that went down in the time of the regime in Argentina.

Purgatory — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purgatory», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She sat on her bed waiting for him, her hands shaking. Nothing could appease her father when he was angry. Emilia knew that the only sensible thing to do at such times was to say nothing, to retreat into herself like a tortoise and wait for the storm to pass. She and Chela had long since learned that their mother’s anger could be placated with a hug. Her father, on the other hand, did not understand such affection. His feelings, if he had feelings, were like ice and never appeared on his face. On those rare occasions when he touched her, Emilia bristled and felt an irresistible urge to pull away. It was an almost animal instinct which her mind ignored. Dupuy’s reactions were unpredictable and the way he was behaving now terrified her. She pulled her legs up onto the bed, hugged her knees to her chest. Simón, she whispered, Simón.

She heard footsteps. Heard him opening the drawers of the cupboards and the wardrobes, slamming them shut, moving the tables in the hall. If her mother had been there, she would have rushed to her side to protect her. But they had taken her back to the home on Sunday. She was alone. At any moment, Dupuy would burst into her room and demand an explanation. She would give him one. As soon as he was calm, she would talk to him. She stared at the glimmer of light creeping through the window. It would be dawn soon. If today was like every other day, her father would soon begin his inflexible routine: the bath, the frugal breakfast of coffee, the round of meetings. It was possible he wouldn’t have time to talk and she could go back to bed. She was half dead with exhaustion.

The double doors of the bedroom opened slowly, Dupuy standing between them, filling the space completely. ‘Make yourself decent this minute,’ he ordered. He gave her no time to take her robe from the hanger but grabbed her by the arm and dragged her to the dressing room which Ethel had used when she was still allowed to make decisions for herself. The walls and the ceiling were covered with mirrors leaving only the parquet floor. It had been one of Ethel’s expensive extravagances; she liked to linger there contemplating the fleeting reflection of her body in the world. As a little girl, Emilia had been afraid that the mirrors would swallow her mother up and the woman who emerged would not be the same, but someone who looked like her. One afternoon, finding the dressing room door ajar, she had steeled herself to sneak in to take a quick look. She saw nothing to justify her fears; dresses hanging from a chrome rail flanked by shelves which held hats, shawls, scarves, gloves, bras, silk stockings, lace panties. And everywhere there were shoes, hundreds of them. As she tiptoed out, she was startled to see her night light come on as though the mirrors were a siren song calling to it.

After her mother became ill, the room, like many in the house, fell into disuse. Dupuy ordered that the clothes be given to the Sisters of Charity and had the shelves and the rail removed, postponing until later the delicate task of removing the mirrors, replastering and repainting the room. He would have it done while he was away on business, when he wouldn’t be bothered by the comings and goings of builders, the hammering, the paint, the dust.

That morning, it occurred to him that the room could also be used to punish. Very few people have a phobia of mirrors, but in those who do the effect is magical and immediate: a strange and subtle form of torture. Emilia had struggled like an animal whenever Ethel had asked her to go in. To him, and perhaps to Ethel, it had merely been an amusing game. But their daughter’s terror was genuine. Mirrors gave her nightmares, made her lose control of her body. He was glad he had not had them removed. Now they would be the perfect means by which his daughter could pay for her crime. He knew her all too well. She was a resentful girl who had thought she could keep the queen’s cape as a trophy. This was why she had taken advantage of the crowds to exchange one for the other. She didn’t give a damn about the irreparable damage it would cause her father’s spotless reputation. If she were not a Dupuy, he would have turned her in and let the police do whatever they wanted, but while she still bore his name he could not do so. The mirrors would break her once and for all and, if he was lucky, turn her into a vegetable like her mother.

Collapsed in a heap next to the dressing room, Emilia no longer struggled. Dupuy pushed her inside, threw a blanket at her and said, as he closed the door: ‘You’re not coming out of there until the other cape is found. And if there is no other cape, you’re never coming out. You’re dead to me. And you can forget about your mother.’

Though sounds from outside the room were muffled, Emilia thought she heard him leave. She would not let herself be beaten by her fears. She had already been locked up for a whole night and she had survived. Simón was with her, Simón was her rock. So as not to lose her head, she would keep her mind a blank. No thoughts, no images, like Buddhists. Only the zero that was God. She would die of exhaustion, of fever, of madness, of anything rather than let her father hear her scream or beg or grovel. Her throat felt dry. She would hold out. (The night light was not as bright as her childhood memories of it.) If there was anything of her in the mirrors, she did not see it. She could make out a few blurred images of some other being. In primary school, she had been told to read Through the Looking-Glass where reality was reversed. Alice did not disappear, but she was unreachable; no one could catch her. Ever since, she had had recurring dreams about that strange world. On the last page of Through the Looking-Glass it says that people in a dream can also be dreaming of us and that if those dreamers should wake we would flicker out like a candle. Emilia did not care whether she flickered out if the dream meant having Simón back. It even occurred to her that Simón might be drawing maps of the infinite in which words and symbols were reversed. She was exhausted, her throat burned with thirst. She lay on the floor of the dressing room, leaned her head against one of the mirrors and gradually fell asleep in the secret hope that the glass and quicksilver would melt into a silver cloud just as it did in Through the Looking-Glass and she could leap across the threshold to a place where everything would begin again.

When she woke, she saw that someone had left a bottle of water in the room while she was asleep, a full teapot, some toast and some cheese. Bringing food all this way and bending down to set them on the floor was not something Dupuy would do. If someone else knew she was locked in here, it was a sign that she would not be left to die. But they were obviously not going to let her out either. The mirrors formed a smooth wall with no cracks, concealing the lines of the door. She felt as though she were in a tomb, sealed up forever. Her eyes were now able to make out the empty space weakly lit by the lamp paradoxically called a night light. Emilia ate and drank only what she needed and put the water that remained to one side. She felt more confident. Seeing herself endlessly reflected in the mirrors had a hypnotic effect. She brushed her face against the smooth, indifferent surface. I can see my whole body, standing, she thought. My face sees the whole body, disappears into the mirror and finds paths there, but what about the rest of my body? Why is there no sense of sight in the mind that thinks, the nose that smells, the vagina that pulses? Was she one being or was she many? If many, how would Simón ever manage to find her? Perhaps he could see her from the other side where reality was inverted and was trying to reach her, unable to recognise her among all the reflected Emilias. She remembered a movie with a scene at a funfair, in a Magic Mirror Maze. A man was trying to kill another man; a woman was trying to kill one of the men or maybe both of them, she wasn’t sure now, but in the mirrors there were lots of men, whole cities of people, lights that multiplied. Emilia thought that with a little patience she could loosen a block of the parquet, take it out and use it to smash the mirrors. She ran her fingers along the floor, feeling for a crack, but it seemed solid. Near the edge, her fingers chanced upon something unexpected. Taking it in the palm of her hand she saw it was one of her mother’s hairpins which had survived being swept up or sucked up by a vacuum cleaner. That something of her had refused to leave was some sort of secret message, a sign that if something persists, endures, it is because it was created to last. She moved closer to the mirror and saw her mother take Simón’s hand, saw her walking with him towards the white nothingness, saw them both reflected in the ceiling mirrors calling to her. She wanted to go with them but she did not know how to get to the other side, how to pass through. Desperately, she pounded on the mirrors begging them not to leave. ‘I’m coming,’ she screamed, ‘I’m coming, tell me how to get to there.’ They went on walking towards the void, not hearing her, until the whiteness of the other side opened its ravenous lips and devoured them. Suddenly, Emilia saw herself transformed into a thousand hateful people, her whole being waging war on itself, this being that had never struggled to enter reality. ‘Wait for me, I’m coming, I’m coming.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purgatory»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purgatory» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purgatory» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.