Tomás Eloy Martínez

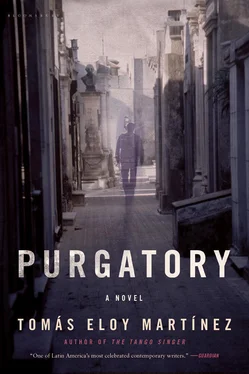

Purgatory

In memoriam Susana Rotker, ten years after.

. what is fleeting remains, it endures.

Francisco de Quevedo ‘To Rome Buried in Her Ruins’

1. Treating shadows like solid things

‘Purgatorio’, XXI, 136

Simón Cardoso had been dead thirty years when his wife, Emilia Dupuy, spotted him at lunchtime in the lounge bar in Trudy Tuesday. He was in one of the booths at the back chatting to two people she didn’t recognise. Emilia thought she had stepped into the wrong place and her first impulse was to turn round, get out of there, go back to the reality she had come from. Fighting for breath, throat dry, she had to grip the bar rail for support. She had spent her whole life looking for him, had imagined this scene a thousand times, and yet now that it was happening she realised she wasn’t ready. Her eyes filled with tears; she wanted to call his name, run over to his table and take him in her arms. But it took all her strength simply to hold herself up, to stop herself from crumpling in a heap in the middle of the restaurant, from making a fool of herself. She could barely summon the energy to walk over to the booth in front of Simón’s and sit in silence waiting for him to recognise her. As she waited, she would have to feign indifference though her blood pounded in her temples and her heart lurched into her mouth. She gestured for a waiter and ordered a double brandy. She needed something to calm her, to still the fear that, like her mother, she was losing her faculties. There were times when her senses betrayed her; she would lose her sense of smell, become disoriented in streets she knew like the back of her hand, drift off to sleep listening to silly songs that, she didn’t know how, seemed to be coming from her stereo.

She glanced over at Simón’s booth again. She needed to be sure it was really him. She could just see him between the two strangers, he was sitting facing her, talking animatedly to his companions. There could be no doubt: she recognised his gestures, the curve of his neck, the mole under his right eye. It was astonishing to discover that her husband was still alive but what was inexplicable was that he had not aged a day. He seemed stuck at thirty-three, even his clothes were from a different era. He was wearing bell-bottoms — something no one would be seen dead in these days — a wide-collared, open-necked shirt like the one John Travolta wears in Saturday Night Fever , even his long hair and his sideburns were relics of a different age. For Emilia, on the other hand, time had passed as expected and now she was ashamed of her body. The dark circles under her eyes, the sagging muscles of her face were clearly those of a woman of sixty, whereas on Simón’s face she couldn’t see a single line or wrinkle. In the countless times she imagined finding him again, it had never occurred to her that age would be an issue. But the disparity between their ages now forced her to reconsider everything. What if Simón had remarried? It pained her even to think that he might be living with another woman. In all the years of waiting, she never doubted for an instant that her husband still loved her. He had probably had affairs — she could understand that — but after the hell they had endured together, never for a moment had she imagined that he might have replaced her. But things were different now. Now, he looked as though he could be her son.

She studied him more carefully. It frightened her how inconsistent this appearance was with reality. He looked half as old as the age — sixty-three — that surely appeared on his passport. She remembered a photograph of Julio Cortázar taken in Paris late in 1964, in which the writer — born at the beginning of the First World War — looked as though he might be his own son. Perhaps, like Cortázar, Simón had fine wrinkles visible only close up, but his comments, which she could hear, were defiantly youthful, even his voice sounded like that of a young man, as though time for him were an endless loop, a treadmill on which he could run and run without ageing a single day.

Emilia resigned herself to waiting. She opened the Somerset Maugham novel she had brought with her. As she tried to read, something curious happened. Coming to the end of a line, she would run into an invisible barrier which stopped her going on. Not because she found Maugham boring; on the contrary, she loved his writing. It was similar to an experience she had had watching Death in Venice on DVD. In an early scene, as Dirk Bogarde sits, troubled, on the Lido watching Tadzio emerge from the sea, the scene had cut back to the conversation in Russian — or was it German? — between the bathers and the strawberry sellers. At first, assuming the director was giving an object lesson in critical realism, deliberately repeating the holidaymakers’ vulgarities, Emilia waited for the next scene only for the sequence of Tadzio emerging from the sea, shaking himself dry, to stubbornly reappear once more to the delicate strains of Mahler’s Fifth. Two nights later, when she should already have returned the film, Emilia played the DVD again and this time was able to watch it through to its poignant conclusion. She was aware that age had made her more dull-witted, but it was something she felt sure she could rectify with a little more attention.

The voices of the strangers in the booth behind her were irritating. She wanted to concentrate on Simón’s voice, anything that distracted from it seemed unbearable. In a restaurant where it was rare to hear anything other than a nasal New Jersey drawl, the strangers’ approximate English was peppered with interjections and technical words in some Scandinavian language. They were talking about Microstation map-making software, a program also used at Hammond, where she worked. Unwittingly, one of the two began to recite the clichés every cartography student learned in their first lecture. ‘Maps,’ he said, ‘are imperfect reproductions of reality, two-dimensional representations of what are in fact volumes, moving water, mountains shaped by erosion and rock falls. Maps are poorly written fictions,’ he went on. ‘Too much detail and no history whatever. Now, ancient maps were real maps: they created worlds out of nothing. What they didn’t know, they imagined. Remember Bonsignori’s map of Africa? The kingdoms of Canze, of Melina, of Zaflan — pure inventions. On Bonsignori’s map, the Nile rose in Lake Zaflan, and so on. Rather than orienting explorers, it disoriented them.’

The conversation shifted from one subject to another, a ceaseless torrent of words. Emilia remembered Bonsignori’s map. Was she imagining it, or had she seen it in Florence or in the Vatican? The voices of the two men grated on her nerves. She could not quite make out their words, they seemed to reach her ears tattered and ravelled. A sentence that seemed about to make sense was suddenly interrupted by the roar of a fire truck or the animal wail of a passing ambulance.

One of the strangers, a man with a hoarse, weary voice, suggested they stop beating about the bush and talk about the Kaffeklubben 1expedition. Kaffeklubben? thought Emilia. Are they crazy? That tiny godforsaken island to the north-east of Greenland, that Ultima Thule where all the winds of the world veer towards perdition? ‘Let’s try and organise the expedition as soon as possible,’ the gravelly voice insisted. ‘In Copenhagen people think there’s another island even further north. And if it doesn’t exist, there’s nothing to stop us imagining it—’

‘ Let’s think more about that, let’s think more, ’ Simón interrupted them. Emilia started. Though she recognised his voice, there was little trace of the Simón she had known in these words. Here was a man who spoke English fluently, who articulated final consonants — think, let’s — with an English diction beyond the scope of her husband, who could never even manage to read an instruction booklet in a foreign language.

Читать дальше