‘Maybe the time has come to let him go. ’

‘I’ve spent years doing everything I can to make him go. I came to Highland Park to escape from the past, and I almost succeeded. I didn’t go back to Buenos Aires, I stopped talking to my parents. Whole days would go by when I didn’t think of Simón once, didn’t even dream about him. The next morning I would feel guilty, but I would also feel a thrill of victory. Since then, he’s come back, little by little. If I just knew where his body was, I wouldn’t have to go through this agony.’

We had ordered pumpkin soup and tuna salad, but we barely touched the food. Much later I realised that we were so cut off from the real world that it hardly mattered whether we were in Toscana or somewhere else. Emilia seemed desperate to tell her story, though just then she had more questions than answers, more wishes than questions. But her wishes could not be fulfilled, or perhaps they had already been fulfilled without her realising. Nothing is more terrible than to wish for something you believe you can never have.

‘It’s all in the past. Don’t torment yourself.’

‘I don’t. That’s the worst thing: I don’t feel any pain any more. I’ve grown used to the absence of the only person I ever loved. What’s strange is that I know I’m not the same person since I lost him and yet I carry on as though nothing happened. I feel despicable.’

‘You’ve no reason to. Nancy told me you spent fifteen years searching for him.’

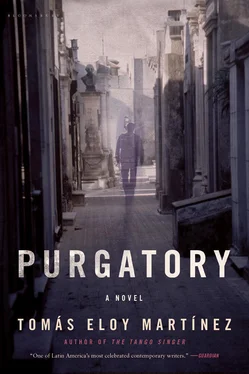

‘Fifteen? I was searching for him even before I met him. Now I’m waiting for him to come searching for me. At Mass last Sunday Father Flannagan’s sermon was about purgatory. The Catholic Church used to teach that purgatory was a necessary purification for imperfect souls before they could enter paradise, that accepting suffering as an act of love for God and all forms of penitence was purgatory. That’s how things used to be. Not any more. The Church is more tolerant these days, Father Flannagan said. Now, purgatory is seen as a wait whose end we cannot know.’

All things come to an end, I told her, even eternity. It was a cliché and as I said it aloud it sounded even more clichéd.

She shook her head.

‘Not Simón. Simón is still there at the door to my bedroom. I know it’s him. He wants me to see him, to let him in. I don’t know how to do it.’

‘It’s not Simón in the doorway. It’s your love for him that won’t leave you in peace.’

‘Simón disappeared one morning in Tucumán. That was thirty years ago,’ she said. ‘For a while I lived out what seemed like a normal life in my parents’ house.’

From time to time, Emilia got messages from people who claimed to have seen her husband dead in this place or that. She went on drawing maps as though nothing had happened. Nothing seemed strange to her. She herself could have sworn she saw Simón at the Country Show or among the visitors to the Buenos Aires Book Fair. He was her God and, like the God of the Church, he was omnipresent. Sooner or later he would return. She had only to be patient. But she could not stop herself worrying when she received these messages about the life he was living far from her. She would lie awake for days convinced that at any moment he would ring the doorbell and explain why he had disappeared without so much as a word. But he never did come, and over time the physical need she felt to hold him in her arms waned. She became resigned to solitude, to abandonment; she began to forget there had been a time when she felt neither alone nor abandoned.

I asked where she had looked for him — cities, beaches, bars, hospitals. As she told me, something inexplicable happened to me. It has no bearing on this story but if I don’t mention it I’ll feel as though nothing that happened that afternoon was real. And it was. We were a couple of blocks from the train station and every now and then we’d feel a blast of wind from a passing train. I looked out the window of the restaurant and, in place of the grey shapes of the buildings, the discount clothing store, the university bookshop, the branches of the major banks that had always been there, I saw the gently rolling pampas outside Buenos Aires, with cows lifting their heads to the sky and lowing as though they too were leaving with the train. Emilia went on talking — about the beaches of Brazil, the mountains of Venezuela, the flea markets of Mexico City — and still I saw the pampas there where it had no business being. In that moment I believed that Simón stood in the doorway of Emilia’s bedroom on North 4th Avenue. I was prepared to believe whatever she told me. If I did not believe her, why was I listening?

‘The first news of Simón that seemed genuine came from one of my father’s sisters,’ she went on.

She was no longer looking at me. I felt like one of her maps. On a map you can be whatever you want to be: the pampas, the Amazon rainforest, a ruined city, an imaginary island.

‘My aunt said she’d seen Simón at the Ipanema Theatre in Rio de Janeiro where she was working as assistant set designer. She’d gone over to say hello but Simón had run off. As soon as I heard this, I decided I had to go there. I spent six months in Rio going from one theatre to another and then from one map company to another. Nobody had heard of him, the whole story was a sick joke.’

I asked her whether she had tackled her aunt about it.

‘I sent her a letter. She never replied. My sister Chela thinks my father put her up to it, asked her to lie to me to get me out of Buenos Aires. The country was in chaos at the time and I think my father, who’d always been so sure of himself, was afraid that I might become a troublesome witness. The thousands of dead, the concentration camps, the unmarked graves left behind by the military junta were just beginning to come to light and my father had sanctioned every one of those crimes. It was more than that — he did not think of them as crimes. After what we now call the dictatorship took power, my father became a rich man, a very rich man. The junta advanced him loans he never repaid, gave him million-dollar commissions, subsidies for public works that had no useful purpose. For my father, it was constantly raining money. He bought land in some of the most fertile areas of the pampas, luxury flats in Paris, in New York, in Barcelona.’

‘Maybe you could move into one of his palaces,’ I said with a sarcasm I instantly regretted.

‘I left Buenos Aires with only the clothes I stood up in and what money I’d saved from my job. Later, I found there was money in my accounts that wasn’t mine and I spent it, but only so I could go on searching for Simón. My father owed him that. My father doesn’t know where I am now or what I’m doing. The only person who knows is Chela, but if she ever tells him, I’ll lose my only sister forever.’

‘Just now, when you said “what we now call the dictatorship ”, I thought you were a collaborator too. I’m sorry. Because what we went through was a dictatorship, the most vicious dictatorship Argentina ever suffered, and God knows we’ve suffered a few. But since you were a victim of it, why do you still refuse to accept they murdered Simón? More than one witness testified as much, it was established at a trial that no one disputes.’

‘Because they didn’t murder him. I didn’t believe it when I left for Rio and I don’t believe it now. Simón is alive. It’s been thirty years and he is still alive. I know. I can feel him inside me. The witnesses saw what they wanted to see. If they blew his head off, as they say, how could the witnesses have recognised him? The only person who could have was me. But I didn’t see him. Simón is alive. I know it. When he comes back, he’ll explain why he left and everything will make sense. Shall I go on?’

Читать дальше