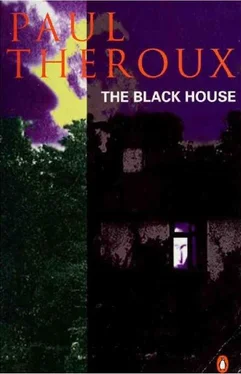

Paul Theroux - The Black House

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Paul Theroux - The Black House» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1996, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Black House

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1996

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Black House: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Black House»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Black House — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Black House», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Ayah's down at the bazaar, is she?” Munday helped himself to the shepherd’s pie.

“I hope they’re not cruel to him.”

“Who?”

“Silvano,” said Emma. “At the pub, in the village —these local people. You said you were going to show him around.”

“Did I?” Munday began to eat. “Oh, yes. That’s right.”

Later that afternoon, Munday sketched out points to be made on notions of time. It was something no anthropologist had dealt with, theories he planned to develop regarding the uselessness of calendar time in folk-cultures—or any culture: how arbitrary it was to count years, one by one, when in reality years were plastic and indeterminate, often reversible, and to travel in space in a given direction might mean losing a century. He would examine the traveler’s platitude about going back two thousand years. (“These people are living in the stone age,” said tourists in Bwamba; they came for the hot springs and the degenerate road-bound pygmies.) It could jar the balance of the mind, this toppling back and forth in time, if you were resident and serious; and the Africans, whose time was circular, moved from century to century in licking a stamp for a bride-price letter, or fixing an axe-head with plastic twine from an Indian shop, or keeping sorcery bones and the clippings of funeral hair in a blue shoulder bag marked BOAC. Munday had experienced the slip of those contrasts. He had shunted from the timeless simplicity of the village, to Fort Portal where the atmosphere was of the 1920s, to Kampala—always ten years behind London—to London itself, which had never ceased to be strange for him. Time was a neglected dimension in the study of man; but it mattered, and one had to consider this in judging people who lived in pockets of inverted time. Munday himself had lurched to the past and back by degrees, blunting his memory in the movement, so his own age was a puzzling figure and all dates seemed wrong. He had seen Africans shattered by the same confusions.

Emma stood at the door. Munday saw her but went on writing. Time is elastic, binding and releasing the—

“I’ve decided to bake a pie,” said Emma.

“Good for you,” said Munday. He saw her lingering, he tapped with his pen. “I didn’t realize apple pies were your strong point.”

“They’re not. But I know where we can get some apples.”

“Splendid.” Munday continued to write—to pretend to. He scratched at the paper.

Emma remained in the doorway.

Munday said, “Off you go.”

“No,” said Emma. “I can’t. You have to get them.”

“Then let’s have the pie tomorrow, shall we?” He

showed her the half-filled notebook page. “I’m rather busy.”

“I must have the apples tonight,” she said, and she added, “Please help me.”

“Can’t you see you’re interrupting me?”

“Alfred,” she pleaded, her voice breaking.

Munday snapped the notebook shut. “This is ridiculous. Apples! Emma, I don’t care if we have apples tonight or tomorrow or never. I’m not interested.”

“You never help me!” Emma sobbed. “I try and try, and you always—”

“For goodness’ sake—”

“You’ve got to go,” Emma said, the lucid appeal coming between her sobs.

“Hold on,” said Munday. Now, he smiled. “Didn’t you tell me today was early-closing? All the shops will be shut. It’s gone four.”

“It’s not a shop,” said Emma. “It’s that place we went before Christmas—that farm on the back road.”

“Hosmer’s?”

“Yes. There was a sign on one of those cottages. Someone sells them.”

Munday tried to remember. “I didn’t see any apples when we were there.”

“I tell you I saw the sign,” said Emma.

Munday said, “You’re making this up.”

Emma came forward and howled, “I’m not! I’m not! Help me, Alfred—you must go now.”

“Send Branch,” he said.

“No—you!” She set her face at him.

Munday got up and held her; she was shaking. He said, “Do calm yourself, my darling. If you want me to go, of course—’’

“You can walk,” she said. The hysteria had wrung her and left her breathless. “It’s not far—down the road, past The Yew Tree, that valley road, where it dips. But if you don’t hurry”—her voice went small, like a child’s disappointed protest—“I won’t have my apples.”

He thought she might be mad, and he recalled what

she had said at lunchtime, everything’s out of reach. He had to reply to her unexpected demand by humoring her. He took the money she offered, a pound note folded into a neat square, and he kissed her and said, “I won’t be long.”

It was dusk, a sea-mist was building in the fields, veiling the hedgerows, and he walked into the falling dark on Emma’s errand. The Yew Tree was shut; one upper window was lighted, the rest held oblong frames of clouds and the last of the sun, breaking through in dim cones at the sea. Munday turned down the lane and walked briskly, putting a bird to flight—it beat its way out of a hedge noisily without showing itself to him—and then to the row of thatched cottages. He hadn’t seen the bam before, but it was there, a rough building of flint and white coarsely-shaped stone beyond the mucky rutted barnyard. And a large sign was nailed to the gatepost on the cottage next to Hosmer’s, apples. Several chickens pecked close to the house; their feathers were muddied on their undersides, but their presence and their color emphasized that some daylight still lingered.

Munday rapped on the door and heard his sounds echo in the house. He peeked through the window. He saw the kitchen table in the center of the room, cruets, a newspaper, a jam jar. He rapped again, then gave up and crossed to the bam, stopping midway to catch a glimpse of the platform where he had seen those dead dogs under the canvas. He remembered them only when he was descending the stone stairs. But they were behind Hosmer’s cottage, those flayed things.

His shoes sucked in the mud as he wrenched the barn door open. At once he smelled the sour decay of apples and saw in warped racks huge cider barrels, rags wound on their wooden bungs, and a cider press, like an early printing, machine, the thick iron screw and the woodframe black with dampness. The paraphernalia leaned at him: a wheelless wagon resting on greasy axles, and hose-pipes and glass jugs and a pruning hook, and on posts supporting the hayloft, harnesses, snaffles, and coils of rope. The apple smell was strong and stung his nose, but there was in its richness something of the earth, a live hum that engaged all his senses. In the wagon were bushel baskets of apples. Munday carefully stepped over the jugs and reached for a basket.

His shadow sank in a wider shadow as the interior of the barn grew dark. It was as if the door had been shut on him without a sound.

“Is this what you’ve come for?”

Munday turned and saw Caroline at the door, blocking what daylight remained; behind her legs a white chicken moved, pecking at mud, bustling in jerks.

“You,” he said. She had given him a fright. He left the wagon and clattered past the jugs, upsetting one. He saw she held a full paper bag against her chest.

“I had to see you,” she said. “I’Ve missed you.” Munday said, “Oh, my love, my love,” and embraced her, kissed her and split the bag of apples. Caroline dropped her arms and released it. The apples tumbled to their shins, fell between them, plopping at their feet, making bumps as they hit and their skin punctured and bruised on the bam floor. Munday stepped on one, skidding on its flesh, ancj hugged Caroline for balance. The apples rolled in all directions, gulping as they bounced.

15

It was a custom among the Bwamba to let their hair grow after a member of the family had died. During this time of mourning their hair sprouted stiffly in a round bushy shape, like a thick wool helmet pulled over their ears. This hair, with their sparse beards, made their faces look especially gaunt, like the pinched ones of defeated men driven into hiding in deep jungle. After a suitable period, and when the affairs of the deceased were settled—all the debts apportioned—the hair was cut with a certain amount of ceremony.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Black House»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Black House» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Black House» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.