“What about, ‘Always be true to the product’?”

“Wise up — you are the product.” Tipple paused to let this apparently obvious concept settle in. “You know you’re the motherfucking man, man. Nothing wrong with hearing it out loud, is there?” The edge in his voice eased. “Bert Nabors is in your digs now, but he’ll understand if we tell him to move. He’s having problems at home, affecting his work, whatever. You should also know that we’ve thrown out the whole voucher system. Top dogs get unlimited car service weekdays. To work, from work, it’s all cool.”

He was more tempted than he cared to admit. Camaraderie. Perks. The very reason for the enormity of his hangover. Those Help Tourists had welcomed him as one of their own, and he missed that brand of companionship. He got a quick glimpse of the view out his old office window. Surveying all below. Everything beneath him. In a rush, he let out the breath he’d been holding in.

“We’re a handicap access building now, too,” Tipple added. “You’ll be very comfortable.”

“I don’t have a wheelchair.”

“I know. I kid. I kid because I love. And also because I am passive-aggressive. We’re not handicap access.” And that was that.

It was almost time for the barbecue. He was tugged toward home and office through Tipple’s phone call, then drawn out to Lucky’s barbecue. Lot of undertow around here for so much dry land. Goode and Field against Winthrop, Regina and Lucky versus Albie. Double crosses. Now Lucky and Tipple allied against him. Too bad Triangleville lacked the necessary oomph.

. . . . . . . .

They were in the woods, the whole team. A few months ago, Tipple had called him into his office to see if he had any thoughts pro or con re: a company-wide retreat to foster brotherhood, teamwork, any number of productivity-boosting notions. He must have been distracted because instead of making a slur, he merely shrugged, which was interpreted as support, and now they were in the woods, a few acres from a pig farm. Occasionally the wind brought the stench over.

From what he could glean, extrapolate, or otherwise mischievously fantasize from the brochure, Red Barn Retreat had been a successful dairy operation some years ago. Then it passed into the hands of heirs who had few kind words to say about farming, and the whole joint was overhauled. The milking equipment sold to the highest bidder, the livestock hustled into vehicles and obscure futures. The exteriors of the buildings were preserved for the feelings of country purity they engendered in the hearts of visitors, while the interiors were chopped up into spaces more appropriate for corporate workshops. The new cattle the place attracted grazed on inadequacy. It was hoped that after a stay at Red Barn — two to seven days, depending on the severity of the situation — the visitors might have learned a different diet, one rich in the nutrients that promoted thinking out of the box and team-playering. It was hoped that all would leave better cows.

Attendance at Red Barn that weekend was mandatory, but everyone knew better than to expect him to participate in the weekend’s activities. He would not repeat the words of the Actualizing Consultant they brought in for the weekend. He would not close his eyes, fold his arms across his chest, fall back, and trust that one of his colleagues would catch him. He was performing spectacularly, and no one was going to make him do anything that might jinx that. Tipple or one of the other managers might have entertained the thought that he’d step in here or there to help out the guys, lend the gift of his experience, but he made it clear from the outset that he would not stray from the sidelines. His names were all the example he was willing to offer.

He spent a lot of time avoiding assorted props. In this room, there were boxes of Kleenex for the inevitable weeping, and then down the hall he’d find straw floor mats, to facilitate the cross-legged confessions about damage inflicted during childhood. Foam weapons lined the walls of the gymnasium, for safe discharge of gladiatorial aggression. It was not clear to him why those assorted clubs and maces were kept behind glass, under lock and key.

That first night he went straight to his room and hid there all night. He thanked God that he got his own room. He had imagined, as they filed onto the bus that ferried them from the city, some sort of summer-camp arrangement of rowed bunk beds. It was enough that he had to work with these people. He was not interested in what they said in their sleep.

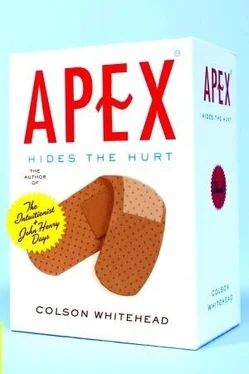

He heard his colleagues rise, rinse, gobble breakfasts. To kill time before they left on their first confidence-building exercise of the day, he changed the Apex on his toe, which at this point was a grisly sight. The daily, sometimes hourly stubbings had taken their cruel toll, and this morning the nail came off with the adhesive bandage, glued fast by dried blood. As he watched, fresh blood seeped up out of the skin. Had Apex been a little more poorly manufactured, it would have slipped off in the shower or in a sock and he would have been aware of the horrible transformation going on under there. Had Apex been shoddier, he would have changed it sooner, but the adhesive bandage looked as fresh as the day he had put it on. The wound had been leaking blood, pus, whatever, but it had all been sopped up by the bandage. His colleagues were out in the hall, or else he would have cleaned out the wound right then. He made a mental note to swab it with antiseptic later. He put a new Apex on the injury. It looked good as new.

When the door to the meadow slammed shut for the last time, he figured the coast was clear and decided to venture out for a walk. Then through the kitchen window he saw the junior staff jog by, shirts off, commanded by this type-A character with a megaphone. They were chanting something, but he couldn’t make it out. More time to kill. He prowled the plant and eventually found himself in the library, the contents of which consisted of what had been left behind. Mostly business self-help, with titles like Be the Network and The Buck Continues: Shifting Accountability in Corporate Hierarchies .

Drawing from Red Barn’s extensive collection, he programmed a film festival of five PR videos. Four of them featured the same narrator, a gentleman of bass enunciation. If his voice had been any lower it would have been magma. The narrator of the fifth video had much less to work with, timbre-wise, but the company had hired some real whiz kids for the graphics end, so that made up for it. Apart from that, the videos were more or less identical, juxtaposing heavy breathing over accordion management, value chains, and rightsizing with exuberant footage of assembly lines, shimmering HQs, beaming customers. A thin broth indeed.

The hours passed. His foot — not just the toe, but most of his foot — pulsed with a dull heat. It was hard to tell who the videos were for, whether the true audience was prospective clients or the producers of the videos themselves. Beneath the bravado, he detected a strong undercurrent of sadness. The narrators protested too much, promised too emphatically; the more stunning and intricate the montages, the more exuberant the editing, the more stirring the orchestration, the less he was convinced. Did they believe in their work, or were they just howling at the heavens? Or howling into mirrors? And his co-workers outside, huffing in circles, chanting slogans and credos, what did they believe? From time to time, his names popped up in the videos, and when they did, he jumped. As if he had been suddenly accused of something.

He needed air. He heard cheerleadering from the front of the house, so he exited out the back, catching his toe on the threshold and cursing. It did not take him long to find himself in the woods.

Читать дальше