His flipping-around stalled when he came across a reference to the Light and the Dark, his favorite dynamic duo founding fathers. He shook his head once more at their crummy nicknames. The top of the paragraph revealed Miss Gertrude Sanders to be rooting through the private diary of one Abigail Goode, daughter of Goode the Elder, aka the Light. He loaned the young correspondent Regina’s face, picturing her in an olde-timey photograph, tinted in long-suffering sepia. Later, he read, she became the principal of the “colored school” in town. Another dutiful daughter in the clan. Abigail, Regina. Deep in that Goode DNA, a certain hardwired rectitude bided its time. He realized that he hadn’t met any descendants of Field. Had he traveled on any streets named for him or his descendants? He’d ask Regina later.

Young Abigail was the main source for Gertrude’s descriptions of the migration from the South. The Goodes, the Fields, and twelve other families lighting out for the territories, 1867. In Abigail’s account, her father came off as the optimist-prophet type, quick on the draw with a pick-me-up from the Bible and a reminder of their rights as American citizens. Uncle Field turned out to be the downer-realist figure, handy with a “this stretch of the river is too treacherous to cross” and an “it is best that we not tarry here past sundown.” His perspective may have been overcast, but from the diary, it seemed that Field had a knack for being right. The Lost White Boy Incident was a good example.

The actual story of the Lost White Boy Incident was very short, but it intersected with what must have been constant concerns for the settlers — where to bunk down, how much to interact with white communities — as well as one particular issue of singular vexation that was timeless, whether it was the 1860s or the 1960s: how to keep white folks from killing you.

The pilgrims were near the end of their journey, a mere few days’ travel from Freedom. They set up camp for the night, having passed enough people on the road to know they were near a large settlement. Had it been earlier in the day, they would have sent one of their more “fair”-skinned companions, White Jimmy, to pick up supplies. (One of the group’s rules seemed to be: When in doubt, send the light-skinned guy.) Night, however, was quick on their heels. They decided against it. Then the Lost White Boy strolled into camp.

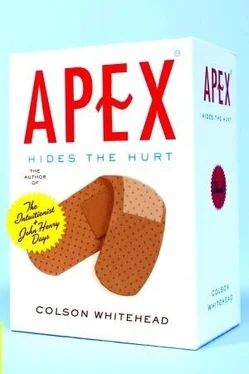

He imagined a cherub out of an Apex commercial: scuffed up, out of sorts, offering up a tiny wound and a low, plaintive “I hurt.” The ensuing back-and-forth must have been very contentious. Where did he come from? they asked. What did he want? they asked. Do we have to adopt him? they wondered. How are we going to keep from being killed once white people find him here? Quite the head-scratcher. The little boy, Abigail wrote, was “mute as a spruce.” He blinked every once in a while, but it didn’t sound like the kid was giving up anything else. If he’d been there, his suggestion would have been to wait a while, and hope the Lost White Boy would wander off again. The sight of the occasional errant roach in his apartment engendered the same caliber of response.

Abraham Goode and William Field were summoned from their no doubt caliph-worthy tents. Solomon time. Goode was of the mind that they had a moral duty as Christians and Americans to help him. A modern translation would be something along the lines of, “We shall return this child to the proper authorities.” In response, Field offered (again in the contemporary idiom), “I think we should point this kid toward the woods and tell his skinny little ass to keep walking,” being of the firm opinion that no amount of explaining was going to keep the Man from bringing his foot down on their collective necks. And just to be safe, the best thing to do would be to pack up and put as much distance between them and him, ASAP.

Now, the Light and the Dark probably commanded their own zones of influence in the camp. He recognized them as a common business pair: a marketing, vision guy teamed up with a bottom-line, numbers guy. You knew what to expect when you knocked on their doors. Upbeat spin on next year’s earnings outlook? Stop by Goode’s office on your way back from break. Wondering if you dare remodel the kitchen next spring? Field will be happy to warn you off, advise you to stick to Cancún for your next big splurge. The homesteaders, he reckoned, sided with Goode or Field depending on what kind of day they were having. Odds were, when the final numbers were tallied, Goode won more arguments than he lost, because he sided with optimism. You didn’t pack up all your shit and trek halfway across the country unless you had a strong optimistic streak. That was the Goode part of you. The Field part of you told you to make sure you brought your shotgun. Musket, whatever.

The more he thought about it, still faintly hungover in his upstairs warren in the Hotel Winthrop, the more the Lost White Boy Incident resonated. These homesteaders had escaped servitude and violence and resolved to put it all behind them. Left that misery at their backs to start their new black town, with their own rules. Whites had their names for what they cherished; these explorers, in their new home, would put their own names to things. Way he saw it, the Lost White Boy, in his slack-jawed, speechless mystery, tapped into this key moment where they had to decide if they were going to continue to deal with the white world, or say: You go your way and we’ll go ours. Decide what exactly was the shape and character of the freedom they had been given.

White Jimmy rode off with the boy in the direction of town.

An hour later as they packed up to flee their camp, White Jimmy told them that the mission had gone well. Until, that is, the merchant asked the boy what he’d been up to the last few hours, it being known around town that the kid had wandered from his parents’ farm that morning. And the kid popped his thumb out of his mouth, pointed it at Jimmy, and said his first words: “The niggers found me.” “As fair-skinned as Jimmy was,” Abigail wrote, “he was as burr-headed as the most Ethiopian among us.” He hightailed it out of the store. The homesteaders loaded up what they could and were on the road “with great alacrity,” as Abigail put it. “When we looked back, all the horizon was lit up as if by a giant bonfire. We knew they had set fire to what remained at our camp, and had we tarried, we would have been ash.” There was always that kindling problem of being black in America — namely, how to avoid becoming it.

Days later, they were here. In Freedom. So to speak. There were many lessons to be drawn from that story, not to mention a moral or two. That afternoon, he settled on one: Listen to the Dark. He was warming up to this Field character. The man had his head on straight.

The phone rang, and for the second time in a week he was talking to Roger Tipple. His old boss wanted to see how he was doing.

“Lemme guess. New Prospera — Albert Fleet, right?”

“On the money. He’s had a really good run this year.” Tipple knew he viewed Albert as a plodder. “How do you like it?”

He heard some ruckus in the background. “Sounds busy for a Saturday.”

Tipple sucked his teeth. “Got our nuts in a vise on this Saintwood Farms thing. These new kids we’re hiring these days, I don’t know.” He sounded genuinely nostalgic. “I’ve missed your joi de vivre and brilliant aperçus. That’s why I called — to make it clear that your job is still waiting for you whenever you want it. And also to underscore that Lucky is a very important client, and if you hook him up, we might even be able to get your old office back.”

“You’re just coming out and straight-up bribing me?”

“Bribe, shmibe, I’m telling it like it is.”

Читать дальше