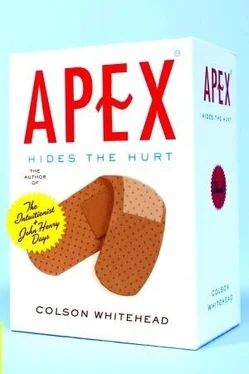

Colson Whitehead

Apex Hides the Hurt

HE CAME UP WITHthe names. They were good times. He came up with the names and like any good parent he knocked them around to teach them life lessons. He bent them to see if they’d break, he dragged them behind cars by heavy metal chains, he exposed them to high temperatures for extended periods of time. Sometimes consonants broke off and left angry vowels on the laboratory tables. How else was he to know if they were ready for what the world had in store for them?

Those were good times. In the office they greeted each other with Hey and Hey, man and slapped each other on the back a lot. In the coffee room they threw the names around like weekenders tossing softballs. Clunker names fell with a thud on the ground. Hey, what do you think of this one? They brainstormed, bullshitted, performed assorted chicanery, and then sometimes they hit one out of the park. Sometimes they broke through to the other side and came up with something so spectacular and unexpected, so appropriate to the particular thing waiting, that the others could only stand in awe. You joined the hall of legends.

It was the kind of business where there were a lot of Eureka stories. Much of the work went on in the subconscious level. He was making connections between things without thinking and then, bam on the subway scratching a nose, or bam bam while stubbing a toe on the curb. Floating in neon before him was the name. When the products flopped, he told himself it was because of the marketing people. It was the stupid public. The crap-ass thing itself. Never the name because what he did was perfect.

Sometimes he had to say the name even though he knew it was fucked up, just to hear how fucked up it was. Everyone had their off days. Sometimes it was contagious. The weather turned bad and they had to suffer through a month of suffixes. Rummaging through the stores down below, they hung the staple kickers on a word: they — ex ’ed it, they — it ’ed it, they stuck good ole — ol on it. They waited for the wind.

Sometimes he came up with a name that didn’t fit the client but would one day be perfect for something else, and these he kept away from the world, reassuring them over the long years, his lovely homely daughters. When their princes arrived it was a glorious occasion. A good name did not dry up and get old. It waited for its intended.

They were good times. He was an expert in his field. Some might say a rose by any other name but he didn’t go in for that kind of crap. That was crazy talk. Bad for business, bad for morale. A rose by any other name would wilt fast, smell like bitter almonds, God help you if the thorns broke the skin. He gave them the names and he saw the packages flying over the prescription counter, he saw the greedy hands grab them from the candy rack. He saw the names on the packaging printed over and over. Even when the gum wrappers were bunched up into little beetles of foil and skittered in the gutters, he saw the name printed on it and knew it was his. When they were hauled off to the garbage dump, the names blanched in the sun on the top of the heap and remained, even though what they named had been consumed. To have a name imprinted along the bottom of a Styrofoam container: this was immortality. He could see the seagulls swooping around in depressed circles. They could not eat it at all.

. . . . . . . .

Roger Tipple did not have a weak chin so much as a very aggressive neck. When he answered Roger’s phone call, it was the first thing he remembered. He had always imagined it as a simple allocation problem from back in the womb. After the wide plain of Roger’s forehead and his portobello nose, there wasn’t much left for the lower half of his face. Even Roger’s lips were deprived; they were thin little worms that wiggled around the hole of his mouth. He thought, Ridochin for the lantern-jawed. Easy enough, but at the moment he couldn’t come up with what its opposite might be. He was concentrating on what Roger was saying. The assignment was strange.

He hadn’t kept up with Roger since his misfortune, as he called it. He hadn’t kept up with anyone from the office and for the most part, they hadn’t kept up with him. Who could blame them really, after what happened. Occasionally someone reached out to him, and when they did he shied away, made noises about changing bandages. Eventually they gave up. He wasn’t expecting the call. For a second he considered hanging up. If he’d planned it correctly, he would have been in a hermit cave in the mountains, two days’ trek from civilization, or in a cabin on the shore of a polluted lake when Roger phoned. A place where you can get the right kind of thinking done for a convalescence after a misfortune. Instead, there he was in his apartment, and they just called him up.

He was watching an old black-and-white movie on the television, the kind of flick where nothing happened unless it happened to strings. Every facial twitch had its own score. Every smile ate up two and a half pages of sheet music. Every little thing walked around with this heavy freight of meaning. In his job, which was his past present and future job even though he had suffered a misfortune, he generally tried to make things more compact. Squeeze down the salient qualities into a convenient package. A smile was shorthand for a bunch of emotion. And here in this old movie they didn’t trust that you would know the meaning of a smile so they had to get an orchestra. That’s what he was thinking about when the phone rang: wasted rented tuxes.

He could almost see the green walls of the office as Roger spoke. Roger’s door ajar and the phones on all the desks out there doing their little sonata. If a particular job was really successful the guys upstairs sent a bronze plaque to your office, with the client’s name and your name engraved on it, and below that whatever name you had come up with. Roger had a lot of plaques, from before he became a manager, from when he was a hotshot. His former boss came into focus as he listened. He saw Roger tapping his pen, crossing out talking points and notes-to-self as he explained to him how this kind of job wasn’t appropriate for the firm because of conflict of interest, and how the client had asked for a recommendation and he was top of the list. It wasn’t appropriate for them but they’d take the finder’s fee.

There was some token chitchat, too. He found out that Murck, the guy the next office over, his wife had had another baby that was just as ugly as Murck Senior. That kind of stuff, how the baseball team was doing this year. Roger got the chitchat out of the way and started to talk about the client. He had turned the sound off on the television but he could still figure out what was going on because a smile is a smile.

If Roger had called a week ago, he would have said no. He told Roger he’d do it, and when he put the phone down it came to him: Chinplant . Not his best work.

. . . . . . . .

He was into names so they called him. He was available so he went. And he went far, he took a plane, grabbed a cab to the bus station, and hopped aboard a bus that took him out of the city. He pressed his nose up to the glass to see what there was to see. The best thing about the suburbs were the garages. God bless garages. The husbands bought do-it-yourself kits from infomercials, maybe the kits had names like Fixit or Handy Hal Your Hardware Pal , and the guys built shelves in the garage and on the shelves they put products, like cans of water-repellent leather treatment called Aquaway and boxes of nails called Carter’s Fine Points and something called Lawnlasting that will prevent droopy blades. Shelves and shelves of all that glorious stuff. He loved supermarkets. In supermarkets, all the names were crammed into their little seats, on top of each other, awaiting their final destinations.

Читать дальше