. . . . . . . .

One day he stubbed his toe. In retrospect there was some inevitability tied up in said stubbing, so he came to believe that his toe wanted to be stubbed for reasons that were unknowable. Unnameable.

The C-line apartments in his building were renowned for their spectacular troves of closet space, and as it happened he lived in 15C. Where lesser mortals were forced to retain the services of storage facilities, the C-liners rejoiced in walk-ins that but for a quirk of fate might have been additional bedrooms. He reserved two of those uncanny closets for the numerous boxes sent to him from grateful clients. In the boxes were gifts. Or gratuities, more like it. Little tips.

They were things he had named. On the sides of the boxes the names loitered and slouched, matured by design teams and promotional schemes into adolescents with personalities. To look at the logos, his former charges had grown up to be flamboyantly calligraphic or dourly industrial or irreverently trendy. The standard arguments over nature and nurture applied.

Most of the products were of no use to him. Space-age spatulas, automatic bird feeders, piquant ointments in various strengths — they represented the breadth of the world. One Christmas he sorted through the boxes, gift wrapped certain items, and sent them to loved ones. The response was less than enthusiastic and the next year he returned to gadgets and doodads. The gadgets and doodads, like his clients’ products, remained in their packages, but he was of the mind that when it came to gifts, it was the appearance of thought that counts.

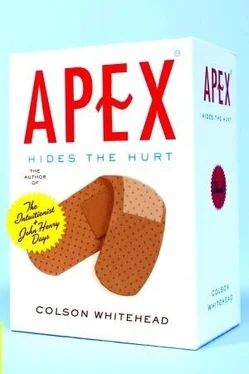

Of all the stuff in his storage closets, the only thing he had time for was Apex. It was hard to argue against the utility of an adhesive bandage and in those early days of Apex, he, like many citizens, found it near impossible to contradict the reasoning of the multicultural bandage, which so efficiently permitted the illusion of a time before the fall. When he stubbed his toe that fateful day, it was toward a box of Apex he hobbled.

He didn’t know what tripped him up. He couldn’t remember after all that happened what he stubbed his toe on. Later he decided the specifics were not important, that the true lesson of accidents is not the how or the why, but the taken-for-granted world they exile you from. In all probability he stumbled over something small and insignificant, as is only appropriate for such a shriveled, gargoyle word like stub . He remembered going into the bathroom and reaching for the box of Apex. The box was his color; they had seen him in the office and knew his kind of brown. He sat on the toilet and removed his shoe. There was a little bit of blood on his sock, and when he pulled it away, he was surprised that his toe did not hurt more. Poor little guy! It looked terrible. The toenail tilted up out of a murk of thick blood, cotton lint, and gashed flesh. It could go either way. The nail might do a little knitting-back-together thing and heal, or it might fall off as a scab. He didn’t care. He put on an Apex.

Which toe was it? One of the shy ones, not the big toe, or the middle, but the one next to the pinky. It sat at the back of the class and did its homework, not likely to be voted anything. Never Best this, or Most Likely to that. The brown adhesive bandage was such a perfect tone that it looked as if he’d never had a toenail at all. That he had never stumbled.

Did it hide the hurt? Most assuredly so.

. . . . . . . .

He was fortunate the next morning that his bed was big enough to accommodate both hemispheres of his hangover. He’d wake up for a few minutes to experience paranoid hangover (these people are out to destroy me), then fall asleep and wake up half an hour later way on the other side of the king-size bed, enduring anxiety hangover (if I weren’t so worthless, these people would not be out to destroy me). He rolled back and forth across the bed, between maladies, disparate throes, for most of the a.m., ruing his decision to partake of the free shots offered by the partying Help Tourists in the hotel bar. He’d intended, after his jaunt with Regina, to get some sleep. Instead, some of the people he’d met with Lucky the previous night had glimpsed him by the elevators and dragged him over. Then he had been enticed with a special shot-glass version of the Winthrop Cocktail. Repeatedly enticed.

He groaned. Twitched. He couldn’t tell if his latest encounter with the cleaning lady had actually happened, or if it had been sculpted from the rough clay of his sundry personality defects. The incident, real or imagined, started with the standard loud statement of intention by the cleaning lady. He did not answer — and then he heard a key in the door. But he could not move, from fear or alcohol poisoning. In his paralysis, he heard the door open — and then stall on the chain, which he had somehow remembered to hook before passing out. The door argued with the chain, once, twice, and then this sinister whisper slithered forth, chilling his soul: “I’m going to clean this room! Clean it up! Clean it up! Clean it allll up!” Then nothing. He woke up on the paranoid-hangover side of the bed, trembling faintly.

Around noon the phone rang and he answered it, purely to test if he was capable of routine physical acts. Caught off guard in the midst of this experiment, the receiver smashed to his face, he agreed to meet Beverley at Admiral Java. It took him a few moments to realize that Beverley was the librarian. He looked for some unwrinkled clothes. Safe from the housekeeper’s influence, and under his slobbish tutelage, his room was magnificently dirty, in a state of happy and familiar slovenly disrepair. It had taken a few days, but he had successfully re-created some of the comforting sights from his life back home, with shirts dangling off chairs and doorknobs, and rumpled pants crawling across the floor. A proper nest. He rescued some promising artifacts and beat it downstairs.

“I said I’d call you if I found anything, so here it is,” she said. She slid a cardboard box across the stainless steel counter. A red ribbon embraced the box, tight and vivid against the ancient cardboard. Outside on Winthrop Square, residents and Help Tourists strolled in the proud afternoon. The weather had cleared up for the barbecue. He didn’t put it past Lucky to bribe whole weather systems, swapping favors for stock.

Beverley tapped the box. “Back in ’37,” she said earnestly, “George Winthrop commissioned Gertrude Sanders to write a history of the town.”

He told her he had a copy of it already.

“You don’t have this one,” she said, rolling her eyes. “Her first draft wasn’t ass-kissy enough, so they made her change a lot of it. The one they published was the happy-face version. I went through this,” she said, running a fingertip across the box, “when I was doing the research for Lucky. There’s some cool shit in it. Not a lot of juicy scandals, but the old bird really had a way with primary sources. I respect that.”

His tongue felt two times too big for his mouth. He took a sip of coffee and knew the caffeine was going to render a harsh indictment to his system when it kicked in. Well, it was nice of her to go to all that trouble. He told her so.

“You’re going to like it,” she assured him. “Remember when you asked why they put the law about naming on the books? I think it was for protection. It was the second law they made. You know what the first one was? That you need a majority on the city council to do anything. They thought it would always be the same way — the two of them on one side, and Winthrop on the other. They thought they could control him.”

“We know how that worked out,” he said.

Beverley’s lipstick, the barrette in her hair, were the same shade as the ribbon on the box. He imagined a whole store, a five-and-ten, that sold everything you might need in the exact same color: sheets, toothbrushes, pots and pans, lamps. The store cut up into a blue section, a yellow section, etc. The orderly and color-coded world. Then he realized he was thinking of Outfit Outlet gone amok.

Читать дальше