On the sides of the boxes were pictures of things you could make out of Ehko bricks if you followed the example, and for a while the kids followed the example. Then they found out that the fun part was making their own bizarre creations. Deviating from the blueprints. The toy was plastic and so was its meaning. He figured there was some mathematical way of determining the exact number of permutations, but the overall impression was that there was no end to what you can make out of Ehko. Parents who played with Ehko as children bought the kits for their own children, and Ehko was passed down alongside morals and prejudices and genetic predisposition to certain illnesses.

The march of time. Over the years, Ehko International started stamping out more extravagant sets, like Ehko Stock Car Racing Track and Ehko Metro Hospital. Again, the kids could follow the plans and make a sterling HMO, or stray and come up with their own, more realistic concoctions, like a hospital without a waiting room, or one equipped with a particularly large morgue. The bricks as the very components of imagination. Every year the company unleashed another dozen sets, each new batch more baroque and complicated than the last: Ehko Andromeda Space Station, Ehko Lost City of Atlantis. Made wistful by the cumbersome boxes they hoisted from the toy store, parents wrote to Ehko International inquiring about the simple kits of their youth. One such favorite was Ehko Village.

Ehko Village had been quite popular during the fifties and early sixties. The Town Hall, the Fire Station, the Church, easily replicable from diagrams, addressed innate notions. Something about this country. But alas the counterculture, the political tumult, the odd riot put a kibosh on sales. Times had changed, but the letters from the now grown-up architects of Ehko Village told the corporation that maybe an update was in order. Being Swiss, they had a very reliable system of dealing with customer feedback. Sentiment rattled its cage. Maybe, they thought, the same concept would fly again, if reworked a bit. But they definitely needed a new name.

He met the Ehko team in the conference room and they outlined their plans, these Swiss people. They were a flock of blond birds, misled by the wind to a city where the going rate was mongrel pigeon. He pretended to listen but the whole time he had his eyes on the box containing the new Village. Once they were done talking he told them to ask the receptionist for some tickets to a Broadway show, if they were so inclined. Strip club passes if they weren’t. He had his own evening already mapped out.

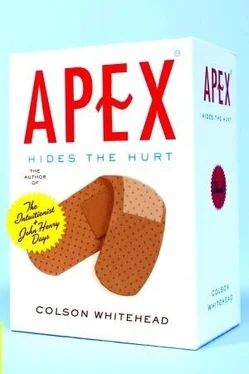

He took the kit home. How could he resist? The pieces fell in a clatter when he overturned the box onto his living-room floor. The proposed town as pictured on the box was an unassuming thing, compared to what the company had been churning out lately. It was out of step with the rest of the product family and out of step with the spirit of the times. It was no Ehko Boomtown Gone Bust or Ehko Ghetto. The machines, he noted, had not been configured to stamp out the little studded bricks of Ehko Abraham Lincoln Public Housing or Ehko Methadone Clinic. (He enjoyed himself more back then.) In the pictures on the box, there were no shadows in the alleys, for there were no alleys. Everything fit together snugly, and there was no place where an unruly element might find purchase.

Some things were different, he observed, but the steps they had taken to modernize the Village pointed more toward demographic reality than slippery, more elusive concepts. The citizens of Ehko worlds were bulbous moppets with painted smiles; as they did in all their sets these days, Ehko included brown bulbs (that were not too brown) and yellow bulbs (that corresponded to some hypothetical Asian skin pigment) according to ratios informed by sales research. This new Village was integrated. And should a child desire to place a fireman’s helmet on a female Ehkotian, it would fit. No longer would pesky perms forbid entrance to the gates of equal opportunity. The shops came in wider variety, and now children could snap an ice-cream shop together or a drugstore. The bricks had not changed, however. Red white and blue bricks still waited patiently for little fingers to quicken them.

His legs remembered the correct position for squatting down with toys. He played. He fit the round male studs into the round female grooves. He got some thinking done as he hunkered down on his fallen-asleep legs. As he cycled through an array of recombinations, his subversive attempts at city planning, the strangest things occurred to him. Sinister and malformed architecture emerged from the pile, ruins slowly revealed by shifting dunes. He could make out the police station in the rubble. If he left it there, in fragments, would there be no crime? By constructing some sort of fascistic multiplex out of the movie theater bricks, it would, according to his logic, call into creation a new cinema, one appropriate to such a venue, but what sort of films would they be? By leaving out the hospital would the citizens not die? Like the plastic of their flesh and the four letters of the name imprinted on every brick, the citizens would live forever. He could leave out the streets and jam the buildings together into a horror of overcrowding, where no one ever went outside into the poisoned atmosphere, but remained behind the walls of Ehko Dystopolis.

From such a simple assignment, all manner of devilment popped into his head. And of course that’s what Ehko was about, he realized. The little children’s hands would be like giant’s hands, the hands of God, reaching down to the floor of the playroom, building this community and world from interlocking parts, every sure snap sound the affirmation of nature’s logic, or at the very least splendid Swiss design. Revoking order only to affirm it anew the next afternoon. The multicolored pieces spread out on the floor like the spiral arms of a galaxy. Which made him universe-big, and he wondered then, what was this toy, and what was this game?

Eventually he followed the instructions. He felt compelled to. In the end nothing was so pleasing as the image on the cover of the box, and this was a lesson to be learned. The original idea remained in that jumble of bricks, patiently waiting.

The kit was still in his apartment, at the top of the closet. He hadn’t the heart to throw it away.

They hired him to make the tough calls. He returned to them Ehko Village. Which, he had to admit, didn’t seem like a tough call at all. It wouldn’t win any awards. Some people, he knew, would say: Well, you didn’t really name anything at all, we could have done that. They’d be right, but they would have done it for the wrong reasons, he countered. After Ehko Space Station Delta and Ehko Martian Invasion Armada, a trip back to Ehko Village was a bold choice. It did not need to be updated. It did not need to be renamed. We have forgotten, he told his clients, we have forgotten the old ways. And the old ways have a name, and they have a power. Malevolent imaginings might try to force those pieces into something they are not, but the name will force them into the correct and kind configuration. We are too easily unmoored these days, he said, and the name will keep us tethered. Ehko Village said values were constant, that times had changed but an idea of ourselves still remained. There is a way of life we have forgotten that is still important.

He didn’t believe that crap, but that wasn’t important. He knew it would strike a chord. The Village was off to the side and timeless. Driving off the main highway one day you might find it and wile away a few hours savoring it. The very name Ehko, after all, what was it? It was what we knew bounced back at us from the walls of the cave, in diminishing repetitions, until it disappeared and we were alone with a memory. So how to stop that? Ehko Village was a reverberation of America that did not grow faint with time. It was always there to play with us.

Читать дальше