The moment stretched. Then he said, “Huh?”

“Are you keeping it real?”

“Sorry?”

“Are you keeping it real?”

“What?”

“Are you keeping it real?”

“What?”

“Are you keeping it real?”

“Yes.”

Jurgen squinted off into the distance. “I think that’s about all I have. Is there any question I haven’t asked that you’d like to be asked, and then talk naturally about?”

“No.”

“What’s your favorite color?”

“Blue.”

“Let’s say green.” Jurgen stood up quickly and extended his hand. “Thank your so much for your time. You’ve been really helpful and this was very refreshing.” And with that the reporter scurried out of the lobby to forage for the winter.

The man had been sent by Lucky, to soften him up for their meeting the next afternoon. His anger toward the housekeeper intensified acutely, and he marveled: she was a fine surrogate indeed. Can’t a brother get five minutes to himself without being hustled by some faction or other? The lyrics of a crappy ditty cavorted in his head: Where’s a brother gonna find peace in Winthrop? / Shuttle bus shuttle bus shuttle bus . The backup singers sashaying, hips a-rocking here and there.

The only thing that salvaged his meeting with the reporter was the sight a few minutes later of the DO NOT DISTURB sign on the door of his room. He crept inside. His room remained unmolested. It was starting to look like home in there, messy and dim. A whiff of something sour.

He was going to take a nap when he noticed the housekeeper’s second note. This one was more economical. It read, “You THINK you are so smart, smarty-pants. But you ARE NOT.”

He scrambled under the covers. Shuttle bus, shuttle bus, shuttle bus.

. . . . . . . .

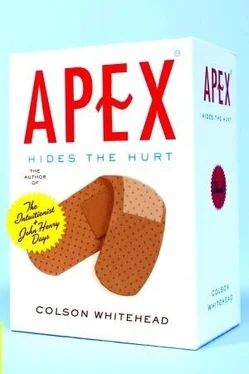

The first time he saw one of the ads he was watching prime-time television. One of the ensemble dramas in the top ten, a show they all agreed on. The commercial opened onto a middle-class suburban kitchen, the kind made totemic in previous commercials, with a little window with yellow curtains above the sink, through which he could see the backyard and the wood fence that kept the neighbors away. A white mother stood with a dishrag in her hand and a white child (Shade # A12) ran in. He looked up abjectly and said, “I hurt.” Then they cut back to the shot of the kitchen, but this time there was a black mother standing there with a dishrag. A black son (Shade # A25) ran into the kitchen and said, “I hurt.” The scene was repeated with an Asian kid (Shade # A17), again with the identical setting and physical movements. “I hurt.” Then came a shot of a white maternal hand fixing white Apex on a white child’s forearm, black maternal hand, etc. Then shots of the mothers holding their children’s smiling heads to their aprons as the tagline manifested itself on the screen and wafted through the speakers: Apex Hides the Hurt.

You couldn’t escape the commercials. Pretty soon the tagline became a universal catchphrase in the way that these things happen. People could take it out of the box and apply it to all manner of situations. Why ya drinking so much Larry? Hides the Hurt. What were you doing on the couch with the babysitter, Harry? Just Hiding the Hurt, honey. The subterranean world of novelty T-shirt manufacture took note and soon ribald takes on the slogan appeared on 50–50 cotton-poly, filling the shelves of tourist traps and places surly teenagers might wander. On the late-night talk shows, there was at least one Hides the Hurt punch line per week. Everybody laughed as if it were the first time they had heard it.

But what was a name and an ad hook if it didn’t move the product? The product moved. The boxes didn’t say Sri Lankan, Latino, or Viking. The packages spoke for themselves. The people chose themselves and in that way perhaps he had named a mirror. In pharmacies you started to see that motion —folks placing their hands against the box to see if the shade in the little window matched their skin. They gauged and grabbed the box, or moved to the next and repeated the motion until satisfied. And Apex stuck. Once you went black you didn’t go back. Or cinnamon or alabaster for that matter. Stuck literally, too. They finally fixed the glue.

In the advertising, multicultural children skinned knees, revealing the blood beneath, the commonality of wound, they were all brothers now, and multicultural bandages were affixed to red boo-boos. United in polychromatic harmony, in injury, with our individual differences respected, eventually all healed beneath Apex. Apex Hides the Hurt.

“Isn’t it beautiful?” he would ask, as he wrapped up the story of Apex. He meant the bit about the multiculture, skinning knees on some melting pot playground. Hey man, it was this country at its best. They were all stones gathered in a pyramid. And on top — well he didn’t have to draw a map, did he?

He never did meet the guy who came up with the tagline, just like he never met the guy who came up with the idea. They were individual agents in a special enterprise and there were no Christmas parties for people like them. They didn’t get together but they still knew each other. They kept this place running.

. . . . . . . .

Riverboat Charlie’s had neglected so many branding opportunities that he wasn’t sure whether to blame a lack of imagination or to applaud that quality, so rare these days, of understatement. As he waited for the mayor, he rhapsodized over what might have been. Menus and signage employing the colorful argot of wharf rats and gamblers, a decor artificially wizened to simulate exposure to dark and churning water, a mascot-spokesman in the form of a cartoon character or elderly gentleman of stylized appearance. Under his attention, the humble establishment became a vacuum, and all the outside marketing world rushed in to fill every inch and corner, wherever a jubilant little branding molecule might find some elbow room. He was the outside world come inside to bully about.

The waitress led him toward the back, then suddenly altered course halfway into the room, dropping the menus on a table for two by the window overlooking the river. At first he blamed his limp, and the waitress’s desire to minimize her exposure to his infirmity. Then he recognized the make of the table — it was a Footsie, familiar to him from when the name won an Identity Award a few years ago — and he realized she was trying to help the mayor out by hooking her up with a romantic spot.

He took in the evening traffic while he waited. During his walks around town, he’d limited his patrol to the square, never venturing down the promenade. True, the rain had hampered his investigation of the area, but it was a fact that he was not a very curious man. Riverboat Charlie’s was off the main drag, however, giving him a good look at the small pier. It was the first cloudless night of his stay, and people were out enjoying the fine weather. In all likelihood, the building at the foot of the pier had been a warehouse at some point, used by Winthrop to ship his barbed wire out of town, but it had been cut up into tiny shops since. Video store and trinket store and a bicycle shop. At one point it had served a single purpose, served its master. Sure, back in the day, you controlled something like that dock and you called the shots.

Regina materialized across from him before he knew it, preventing any momentary dithering over the right greeting. Hug, cheek peck, or handshake. She was more relaxed this time around, wearing a low-cut blouse that was more daring than he’d given her credit for. “Glad I called ahead,” she said.

In only a few minutes, the place had almost filled up. He recognized a good number of the other diners from the hotel. Riverboat Charlie’s was probably listed as an approved restaurant in the Help Tour Information Packet, after a list of where to change currency in this strange land and the number of the nearest embassy. “It’s never this packed,” she added, “unless it’s someone’s birthday or a holiday or Valentine’s Day.”

Читать дальше