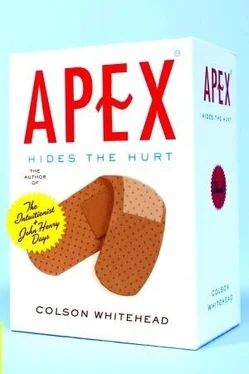

And here he tried to re-create the consultant’s pitch for his listeners. The man walked around the conference room table, provoking the good men in their good suits to reconsider the basic laws of their profession. Band-Aids are flesh-colored, the man said. Most adhesive bandages are flesh-colored. Are advertised as such. And it did not occur to anyone to ask, whose flesh is this? It ain’t mine, and with that the man pulls back one sleeve to reveal his wrist, and the skin there.

The whiz kid said, You manufacture this thing and call it flesh. It belongs to another race. I have different ideas about what color flesh is, he told them. We come in colors. We come in many colors. And we want to see ourselves when we look down at ourselves, our arms and legs. Around the table the men listened, and soon afterward they got to work. Somebody give this guy a raise.

At Ogilvy and Myrtle they knew the neighborhoods, some block by block, and they knew the hues of the people who lived there. They knew the cities and the colors of their mayors. They knew the colors of clientele and zip codes and could ship boxes accordingly.

They devised thirty hues originally, later knocked them down to twenty after research determined a zone of comfort. It didn’t have to be perfect, just not too insulting. What they wanted was not perfect camouflage but something that would not add insult to injury. In the modern style, the gentlemen of Ogilvy and Myrtle learned to worship databases, and linked fingers before altars of data. There was a large population of Norwegian Americans in the Midwest; O and M sent them a certain shipment. And there was a denomination of Mexican Americans in the Southwest; O and M sent them a certain shipment. The cities and hamlets had hues. The shipments were keyed, bands of colors were strategically bundled together. Given their particular business history, O and M possessed long-standing supply networks to poor countries — their cruddy craftsmanship demanded this — and to these poor countries they shipped appropriate boxes to their inevitably brown-skinned populations. The school nurses of integrated elementaries could order special jumbo variety packs, crayon boxes of the melanin spectrum, to serve diversity.

Even he had to admire the wonder of it all. The great rainbow of our skins. It was a terrain so far uncharted. Pith helmets necessary. The fashioners of clear adhesive strips almost recognized this but didn’t take the idea far enough. The world of the clear strip was raceless; it did not take into account that we sought ourselves, like sought like, that a white square of white cotton wadding attached to transparent tape dispelled the very illusion they attempted to create. Criminy — an alien square of white on the skin, well that was outside the pale of even the albinoest albino. The deep psychic wounds of history and the more recent gashes ripped by the present, all of these could be covered by this wonderful, unnamed multicultural adhesive bandage. It erased. Huzzah.

When the consultant looked down at his arm, what did he see? Was the man his color, something else, was he flesh -colored? When the man looked down at his arm, did he observe business opportunities, an unexploited niche, an overlooked market, or something else? The man saw the same thing he saw. The job.

. . . . . . . .

Friday morning he stood before the plywood fence, looking at the COMING SOON OUTFIT OUTLET sign. Head cocked, dumb gaze, stalled mid-step: any observer would have translated his body language into the universal pose of lost . Reception’s directions had led him to this spot. He looked up and down the street, but didn’t see where he could have made the mistake.

A door in the fence scraped inward, revealing a scruffy young white dude whose wrecked posture, rumpled clothes, and shallow expression marked a life of few prospects, and fewer misgivings about the lack of said prospects. An existence lived in the safety and hospitality of that protected nature preserve called the American Middle Class. The name Skip was embroidered over the left breast of his striped mechanic’s shirt, which meant in all probability his name was not Skip. Not Skip awkwardly steered a dolly onto the sidewalk, grunting.

He informed Not Skip that he was looking for the library.

The dude set the dolly level, his hand anxiously frisking the stack of boxes to ensure they did not tumble, and jerked his head toward the door. “They’re closed,” he mumbled. “But you can see for yourself if you don’t believe me.”

Not Skip struggled past him and he glanced up at the Latin phrase engraved above the Winthrop Library’s doorway. That was going to have to go, unless it was Latin for Try Our New Stirrup Pants. Probably not the first time one of his clients had displaced a library, and probably not the last.

On the rare occasions that he entered libraries, he always felt assured of his virtue. If they figured out how to distill essence of library into a convenient delivery system — a piece of gum or a gelcap, for example — he would consume it eagerly, relieved to be finished with more taxing methods of virtue gratification. Helping little old ladies across the street. Giving tourists directions. Libraries. Alas there would be no warm feeling of satisfaction today. The place was a husk. The books were gone. Where he would usually be intimidated by an army of daunting spines, there were only dust-ball rinds and Dewey decimal grave markers. As if by consensus, all the educational posters and maps had cast out their top right-hand corner tacks, so that their undersides bowed over like blades of grass. Nothing would be referenced this afternoon, save indomitable market forces.

Even the globe was gone. Over there on a table in the corner he saw the stand, the bronze pincers that once held the world in place, but the world was gone. Next to the stand he spied a small messy pile of books with colorful spines, which he momentarily mistook for a pile of This Month’s Sweaters, mussed by grubby consumers and waiting for the soothing, loving ministrations of the salesgirl.

“We’re not open,” she said. “Middle of next week we’ll be open around the corner.” She rounded a bank of desolate shelves, this young white chick with dyed black hair, the twenty or forty bracelets on her wrists jangling like the keys of a prison guard. Salesgirl or librarian? She dropped a load of children’s books on a desk, and wheezed loudly, out of proportion to her burden. Her clothes were dull gray where the light hit them, the faded favorite gray of jet-black clothes washed too many times. He didn’t peg her as homegrown talent, and she made an unlikely librarian, stereotype-wise. Nonetheless, he decided: One bracelet for every shush.

“Oh,” he said.

“Come back next week for all your shopping needs,” she said. “If you need to use the Web, you’re welcome to,” she added, brushing dust off her skirt. “They want us to keep ’em on until we have to turn ’em off.” Along the back wall there was a line of six computers, their cursors blinking impatiently. A pyramid of books anchored one side of the computer table, with one copy face-out on top in the apex, and he recognized the cover of Lucky Aberdeen’s autobiography, Lucky Break: How a Small-Town Boy Took On Corporate America — and Won! Above the computers, the bowed-over corner of a promotional poster obscured the final few words of Lucky’s motto, which, conveniently, was also the publicity tagline: DREAMING IS A CINCH WHEN YOU—

He asked if there were digital archives on the town’s history, which did not strike him as a funny question, certainly not worthy of a smirk. “No one’s ever asked that question before,” she told him, “not ever. All the stuff we have is in good old-fashioned books. And it’s in boxes. You have to come back next week.” Perhaps his face revealed something, although when he reviewed the encounter later, he felt confident that he had not slipped. It was ridiculous to think that he had registered disappointment over something as unimportant as a job. More likely, her librarian instincts had awakened after days of packing things up. She asked, “Is there something in particular you’re looking for?”

Читать дальше