. . . . . . . .

“My wife took it all,” Albie moaned again. They toured the empty rooms. “Took my name and then took everything else.”

He was breaking a rule, one that he didn’t even know he had until he got inside Albie’s place: no house calls. It was depressing. Most of the light fixtures didn’t have working bulbs, so they maundered from room to room in a sullen march, their path illuminated only by the gray light from outside. Sometimes the two men were mere silhouettes, sometimes barely ghosts, and Albie’s words in the air were rattling chains, it seemed to him. He grabbed items from the Hotel Winthrop and placed them on the floors and along the walls to visualize what the place had looked like a generation ago, and fire shimmied in the fireplace, and great tones erupted from the grand piano. These dim visions.

Every new door opened on emptiness, on hollowed-out history. Albie preferred the past tense. It was his new roommate, eating the last doughnut and leaving flecks of toothpaste on the bathroom mirror. “This was the game room,” Albie said, as they sent dust scurrying from their steps. “This was Grandmother’s room,” Albie said, as a tiny square of light squeaked through an attic window.

What was there to say, he wondered, standing in the gloom, holding a paper plate. He said, “Thanks for the hot dogs.”

Albie brightened instantly. “My specialty!”

They started back down the stairs. “You should rent out some rooms,” he offered. Sympathy did not come easily to him, but he knew a fellow patient when he saw one. He had his misfortune, and Albie had his.

“That’s what the hotel is for,” Albie said. “At least I still have that.” He grimaced. “We’re all booked this weekend, every room. For him . Even when I’m making money off him for a change, he’s making ten times more offa me, what Lucky’ll get out of this conference in the long run.”

Only the living room contained more than one piece of furniture, and they sat on the bumpy couch after Albie cleared away magazines and shooed crumbs. Mounted heads stared from one wall, the stuffed remains of the antlered and the slow-moving. Albie saw him looking at them and told him again that yes, his wife had taken everything in the divorce, everything, but he had held firm when it came to the trophies. “A man has to draw a line somewhere.”

“With barbed wire,” he said. He pointed above the fireplace, where a thick braid of metal was mounted on dark wood. Not a trophy but a monument.

“Barbed wire! Drawing a line , exactly! I knew I could talk to you,” Albie exclaimed gleefully. He skipped over to the mantel and ran a finger along the metal. “This was our barb,” he cooed, tracing the butterfly-shaped loop. “Mark of distinction. Every wire manufacturer had their own barb, so you knew what you were buying. People go to buy a new bundle, they’d look at this W right here and know they were buying quality.”

“Your brand.”

“All over the plains, they buy Winthrop Wire, they buy quality. They knew this. Nobody knows about this stuff anymore except people here. And soon. .” His hand fell.

Albie returned to the couch, frowned, and recounted the whole sad story of The Day of the Doublecross. He didn’t know why it had happened, but Regina and Lucky had “bushwacked” him. For the life of him, he didn’t understand. Lucky Aberdeen — why, Albie had embraced the man like a brother, despite all that had gone on between them real estate — wise. And Regina, they were practically blood relations — their families went so far back it was practically historical.

The day of the vote, Albie had just finished visiting old Marcia Newton, who had broken her hip and was bedridden. (He recalled the days after his misfortune, when he was bedridden and unable to escape. It was people like Albie who had made him barricade himself in his apartment during his convalescence.) Albie was in fine spirits when he walked into the meeting, full of his good deed, and ready to discuss the new SLOW CHILDREN signs. The controversy over whether to put up two or four signs had been simmering for weeks, and that day the city council would settle the matter once and for all. Just the three of them at the table, the way it had always been for generations. The city council, the old, benevolent tribunal. Majority rules.

And then Lucky said that they had another matter to settle before they could proceed to the matter of Slow Children: the name of the town. There’s been a lot of talk in town, Lucky told him, about whether or not Winthrop as a name reflects new market realities, the changing face of the community. (As Albie’s mouth formed the words market realities , his lips arched toward his nostrils and his eyes slitted, so sour were the syllables.) Talk, what talk, Albie asked, he hadn’t heard any talk and he was practically the heart of the town. Lucky appeared not to hear him. Lucky kept on with his nonsense. “In that idiotic vest.” Lucky said: It’s been proposed that maybe we should look back to the town charter of Winthrop and invoke the laws that define this town. That maybe we, the city council, should run the numbers and take a vote on whether to change the name of Winthrop to something more appropriate.

“You can imagine what I was feeling,” Albie complained, putting two fingers to his lips and belching. “I tried to get them to talk to me, but they were like stone. I said, ’How could you do this to me, I’m your good old pal.’ Bringing up that old law. It hadn’t been used since they changed the name to Winthrop in the first place. Was it still on the books, I wanted to know, but they weren’t having it. Wouldn’t listen to me. And I tell you, I thought it was a done deal once they won the vote, two to one. I was thinking, how long have they been planning this? Voting to change the name. Digging up some old law no one ever thought to take off the books. Putting one over on Uncle Albie. ‘You don’t do that to your uncle,’ I said. ‘I’m everybody’s uncle!’ I turned to Regina and told her, ‘Regina, look me in the eyes.’ But she wouldn’t look at me. And Lucky went, ‘Now that that’s decided, let’s move on to the matter of the new name itself.’ He brought out that stupid suggestion of his — New Prospera — and went, ‘All in favor, say aye.’ But then Regina double-crossed him, and boy, oh boy, was he surprised! You should have seen his face,” Albie said, his voice cracking. “We sat there deadlocked. Every name — mine, Lucky’s, Regina’s — had one vote, and no one would budge. It was the three of us, and no one would budge.”

Albie looked exhausted.

“This law was put on the books to change the name of the town to Winthrop.”

“It was only a settlement really,” Albie said, “where Regina’s family decided to stop one day. There wasn’t any thought to it. They just dropped their bags here.”

“But what was it called?”

“Oh. They called it Freedom.”

Freedom, Freedom, Freedom. It made his brain hurt. Must have been a bitch to travel all that way only to realize that they forgot to pack the subtlety.

. . . . . . . .

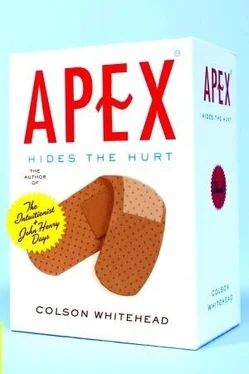

Apex was manufactured by Ogilvy and Myrtle. They got their start in 1896 as commercial suppliers of sterile gauzes and medicinal plasters. From what he could tell, theirs was a small but sturdy outfit with solid distribution in the south, catering mostly to hospitals. He imagined Ogilvy and Myrtle Sterile Bandages being applied to the hip wounds of the day. Got kicked in the head by a horse, fell off a stagecoach, you knew where to go.

Things picked up during World War One, when they put in a successful bid for a military contract. An assured client base of patriotic casualties enabled them to enter the age of mass production. Blood in their business was down-payment money and lines of credit. A couple of years later, once Johnson & Johnson unleashed the noble Band-Aid, O and M joined the adhesive-bandage revolution with gusto.

Читать дальше