When he accepted the assignment, the clients gave him a packet on the competition. Sometimes it was important to know what you were up against. Sometimes it didn’t matter at all. At any rate, when asked about how he came up with the name Apex, which was often, he always kicked things off with a brief preface drawn from the information he received that fateful day.

In the promotion materials for the Johnson & Johnson Company he got the lowdown on the creation of Band-Aids. The year was 1920. The place, New Brunswick, NJ. Earle and Josephine Dickson were newlyweds. He was a cotton buyer for Johnson & Johnson, she was a housewife. He worked for the country’s number-one medical supply company. She cut herself. Repeatedly. Every day it seemed. She was clumsy. She had household accidents. Through the modern lens, he told his audience (a comely young lady at a bar, poised sophisticates at a dinner party, a dentist), he interpreted the young lady’s constant accidents as sublimated rebellion against the strict gender roles of her time. He’d attended a liberal-arts college. Perhaps she wanted to be a World War One flying ace, or a mechanic. He didn’t know. All we have are Band-Aids, he said.

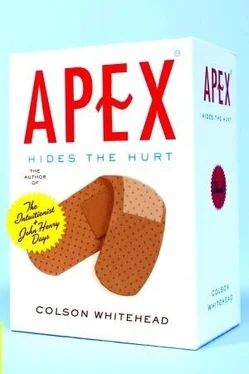

Every day Earle would come back from work to confront his wife’s wounds, cotton wadding and adhesive tape in hand. He pictured her through the screen door, offering her latest domestic tragedy for his inspection when Earle came back from the office, red-eyed, anxious, what the heck, let’s throw in a trembling lip. After a while, Earle decided to take himself out of the equation. He placed gauze at regular intervals onto a roll of tape, and then rolled the tape back up again. That way, whenever Josephine had one of her little cries for help, she could help herself, and if she happened to slice herself while cutting off a patch of tape, well what could be more convenient. Earle of course mentioned this innovation to his colleagues, and the rest was history and brand-name recognition, was Band-Aids, competing brands of adhesive bandages, was Apex, his toe.

. . . . . . . .

New Prospera . If he lifted the whelp by the heel he’d find the birthmark of the Fleet clan. Albert Fleet’s shtick consisted of resurrecting old nomenclature motifs just before they were about to come back into vogue. Old hound dog sniffing, he had a nose for incipient revival. The good ones always came back, the steadfast prefixes, the sturdy kickers. When you counted them out, Pro - and — ant would stumble back to the top, bruised and lacerated but still standing, this month’s trendy morphemes and phonemes lying at their feet in piles. Everything came around again. Languages were only so big.

He had effectively killed off New when New Luno hit it big, and at the time everyone warned him that it would look like he was merely chasing a trend, and that sort of thing was beneath him. Anywhere you looked that year, something was New. But success shushes those kind of accusations. If Albert was lugging New back onto the scene, you better brace yourself for a full-blown renaissance. New was new again.

Prospera , that could have come from anybody on the team. Had that romance-language armature, he was pretty sure it was a Spanish or Italian word for something. What it meant in those languages, that was unimportant, what was important was how it resonated here. The lilting a at the end like a rung up to wealth and affluence, take a step. A glamorous Old World cape draped over the bony shoulders of prosaic prosperity . Couple a cups of joe to clear the head, anybody in the firm could have come up with that one. Everyone a suspect. Prospera left no fingerprints on its gleaming surface.

New, new, new money, new media, new economy. New order. New Prospera. He reckoned it would look good on maps. Nestled among all those Middletons and Shadyvilles.

It wasn’t that bad a name, certainly no masterpiece. When — if — he returned to work, his office would be waiting. They still needed him.

How much did he need them?

That second night in Winthrop, Old Winthrop, he went to sleep at a decent hour. He drifted off reminiscing about the tools of his trade. He drifted off thinking of kickers. Somewhere in the night he had a nightmare. Rats bubbled out of the sewers, poured out of gutters and abandoned buildings. Making little rat noises. They were everywhere, and he knew that even though they wore the skin of rats, they were in fact phonemes, bits of words with sharp teeth and tails. Latin roots, syllables to be added or subtracted to achieve an effect, kickers in their excellent variety, odd fricatives, and they chased him down. They finally cornered him in an old warehouse and he woke as they started nibbling on his vanished toe, which had reattached itself as if it had never been lost.

It was early morning. The sun was up somewhere, rebuffed by clouds. Still raining. He went to the bathroom and when he came out he noticed the envelope that had been shoved beneath the door.

The client had agreed to his conditions.

He was back to work.

HE LANDED APEXbecause he was at the top of his game. The bosses would call him into their office to chat, to reassure themselves, to count the lines on his brow as they ran an idea up the flagpole. One day he stifled a burp and his pursed lips put an end to Casual Fridays. The other folks in nomenclature came to him with their problems, they bought him cocktails and he offered obvious solutions to dilemmas. He wasn’t exactly taxing his brain. He didn’t squander names that could have been used for his projects. What he gave them were slacker names. He lent out malingerers.

He attracted clients through word of mouth. Some clients he passed off on younger, hungrier colleagues and e-mailed apologies. He was all booked up. His generosity increased his estimation in the eyes of the lower ranks and his exclusivity won him still more clients. With the assignments he did take, he was getting faster and faster with his naming. He wasn’t at the point where he could just look at something and know its name, but the answer generally came quickly and he had to sit on the name for a couple of days and pretend to ponder long and hard, or else he’d look superhuman. When he walked down the halls of the office sipping water from a paper cone, hip boots would have been a plus — he waded through a palpable morass of envy. He expected some sort of comeuppance for his efficiency. None came. In fact he was bonused repeatedly. He expected the great scales of justice to waver, for certainly his expertise was upsetting some fundamental balance in the world. There was nary a waver or a twitch. Until Apex.

His life outside of work, that was going pretty fine, too. He hadn’t met that special someone but he went out a lot, made reservations at approved restaurants. Occasionally he extended a hand across the table to spark a soulful gaze. Friends of his set him up with their sisters. He had a kind of vibe he projected. Wage earning. Self-actualizing. Nice catch. A local magazine picked him as one of the City’s 50 Most Eligible Bachelors. He got some mileage out of that and hit the town with new credibility. This is my face, his manner seemed to say. For the photo shoot they had him sit on a gigantic blue pill, because he had named a popular blue pill, and he wore a fine designer suit that he was not allowed to keep. The writer made a few jokes of the what-the-heck-is-a-nomenclature-consultant-you-might-ask variety. One thing about his job, he had conversation starters for sure.

His new apartment was great. There was an extra room he didn’t know what to do with so after a year he got a pool table and an aquarium. He bought exotic fish for the aquarium from a specialty store. Occasionally they ate each other. There were all these fins at the bottom of the tank. Conversation starters for sure. From the balcony he could look down upon the city and think he owned it. And perhaps that feeling was in the mix when he came up with Apex. He looked down on everything. It was all so small.

Читать дальше