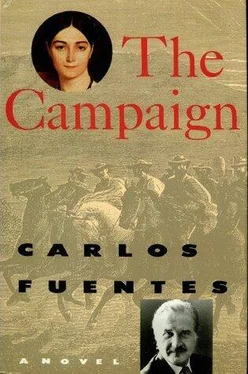

Carlos Fuentes - The Campaign

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carlos Fuentes - The Campaign» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Campaign

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Campaign: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Campaign»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Campaign — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Campaign», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Quintana’s words allowed for no response, and in any case the force with which he led Baltasar to the confessional precluded any appeal.

Baltasar fell into the seat of the confessor with a leaden sense that anchored him there as if in a loathsome jail cell, the mortal facsimile of the coffin whose worn-out velvet smelled of trapped cats.

Anselmo Quintana knelt down outside, by Baltasar’s unwilling ear.

“Yesterday you did not allow me to confess,” said the priest.

“But I told you I don’t believe in the power of absolution.”

“You think I want to talk about your sins, so you shut yourself off from me. But your sins do not interest me. Your fate does. And what I confess to you is also part of my fate. Let’s get started: I confess, brother, to having ordered the execution of a hundred Spanish soldiers held in jails and even in hospitals, in order to avenge the death of my eldest son at the hands of the royalists. I ordered their throats slit. The idea of forgiveness never even passed through my mind. I was blinded. Tell me if you would have forgiven me if I were your father and you my dead son.”

Baltasar said nothing. A feeling of growing modesty was taking control of him, inseparable respect and compassion for this man whose voice was becoming black, thick, guttural, reverting to ancient African roots, almost the voice of a psalmodist, which Baltasar did not want to interrupt until he’d heard everything, the same propitiatory act, perhaps, that would permit a believer to repeat the sacrifice on Calvary without taking the slightest bit away from the sufficiency of Christ’s martyrdom.

He decided to hear him through to the end without arguing, to listen to him speaking there on his knees, his face like an old ball that has been kicked around: “I understand your silence, Baltasar, I understand your reticence, but understand mine; I share your fear of our weaknesses, and I fear as you do that a word spoken in confidence will be taken away by the one who listens to us, will get lost with our secret in the multitudes, and that we shall be left at his mercy if one day, out of despair or necessity, he repeats it to others; if you don’t believe in me, in my priestly investiture or in my power to pardon sins, I shall repeat that I understand you, and for that reason I ask not that you confess formally to me but that you accept my humility as I kneel before you, exposing myself to you as the one who carries away my secret and, not believing in the sacrament, gives my secret to the world. I offer myself to you as an example. I confess before you, Baltasar, because yesterday you said things for which I have to assume some responsibility, and it does not seem right that the burden of our relationship, which has barely begun, which may not last very long, should fall upon me: one day we shall give an accounting not only of ourselves but of each one of the people to whom we have said something or from whom we have heard something. I ask you to accept this and not to believe that yesterday only you spoke, unburdening your conscience, and that today only I will do the same: your responsibility, yours and mine together this morning, is to give an accounting of all the beings who have done us the favor of listening to us. Would you like to know something? I told you my crime against the prisoners, and you should understand that, just as you do when you sin, I committed a crime against universal morality. St. Paul explains that sin is an assault on the natural law inscribed in the conscience of each human being. In my own case, it was also a violation of the vows of the priesthood, which include forgiveness, mercy, and respect for the will of God, who alone is able to give and take away life. Because of what I had done, I feared the punishments of hell that day when I avenged my poor son, a twenty-year-old boy who gave himself to the fight for independence, a gallant fellow with a red kerchief tied on his head, which made it difficult to see the blood when the ferocious Spanish Captain Lorenzo Garrote executed the sentence. Garrote saved his own life and embittered mine … But I realized, Baltasar, that I did not fear the ordinary hell of flames and physical suffering but the hell I imagined, and that hell is a place where no one speaks: the place of eternal, total silence forever; never more a voice, never a word. For that reason I kneel before you and beg you to listen to me, to postpone that inferno of silence, even if you do not speak to me, even if there is a hint of disdain in your stubborn silence. It does not matter, my little brother, I swear it does not matter, as long as we do not let our language die. Listen to me, then: I admit that I rebelled because I was unhappy when I lost my living, but now my rebellion has gone far beyond that. My rebellion led me to one gain after another: this is what I want to communicate to you; this is what you should understand. I gained rational faith without losing religious faith: I could have said, simply, ‘I am a rebel priest; those who excommunicate me are right. I am going to deliver myself over to independence, to the wisdom of the age, to faith in progress; I am simply going to damn religious faith.’ Everything was joining against my faith: my rage when they declared me a heretic and blasphemer, my fear when they denied me the Host, my rancor when they killed my son, my temptation to be only a rationalist rebel. This has been my most terrible struggle, worse than any military battle, worse than all the spilled blood and the obligation to execute: not to give in before my judges, not to admit they were right or give them the pleasure of saying, ‘Look, we were right, he was a heretic, he was an atheist, he deserved to be excommunicated.’ They ask me to repent. They don’t know that that would mean delivering myself to hell. It would mean admitting the absolute evil in me — reason without faith — because I can lose the Church that has expelled me, but I cannot lose God; and to repent would be exactly that, to return to the Church but to lose God — not reason, which can coexist with the Church, but God who can exist without the Church and without reason.”

Quintana lowered his head, and Baltasar saw the tawny-colored cloth of his celebrated cap hiding his curly dark hair, which the priest revealed so as not to stand out from the other men in the encampment, but in so doing he revealed himself with more fanfare than if he’d proclaimed it aloud: only Anselmo Quintana wears a cap amid all these top hats worn by the lawyers and the red kerchiefs worn by the troops; thus, Anselmo Quintana is the man who does not use a cap to disguise himself but who, by the same token, does not wear frock coats or tie kerchiefs on his head and who stares intensely at two bottles in order to choose between good and bad alcohol just as he might choose between reason and the Church. But you can’t just choose God: God is, with or without the Church, reason, or believers. “That’s where I have concentrated my real rebellion,” the priest Anselmo continued. “I’m telling this to you, Baltasar, because you are like my younger brother in the world and you are also rebelling against its laws, but you remain open to new persuasions. My real rebellion was to suffer the Calvary of losing my Church but not my God … Imagine what went through my soul when I took up arms on the Gulf Coast, angry over the loss of my living. Imagine me pug-nosed and blind, just ten years ago, consumed with lust, in love with gambling, with women, a horse’s ass of a priest, with a troop of bastards scattered all over the place, a seducer of women who came to kneel next to me and who thought that, to receive my forgiveness, they had to give themselves to me, and from time to time I did not discourage them … I took up arms, my boy, being the kind of man I was, and then excommunication hits along with the rain of labels: apostate against the Holy Catholic religion, libertine, seditious, revolutionary, schismatic, implacable enemy of Christianity and of the state, deist, materialist, and atheist, guilty of divine and human treason, seducer, impenitent, lascivious, hypocrite, traitor to king and country. They didn’t omit a one, Baltasar. The Holy Inquisition did not omit a single crime. They threw all of them at my poor head, and every time an accusation struck me between the eyes, I would say, ‘They are right; they must be right. It’s true, I deserve this, and my poor, damned motive for rebelling makes me a criminal in all those other things, and that, too, must be true…’ But I think, brother Baltasar, that the Inquisition, as usual, went too far; they accused me of too many things, some right, others outlandish, and I said to myself then, ‘God cannot look on me with as much injustice as my judges. In God’s vocabulary there are probably few words for me, but there most certainly must be a dictionary common to Jesus Christ and His servant Anselmo Quintana. They throw so many words at me, but not enough that every week, from Thursday to Friday, you, Lord, cannot still speak, my Jesus, with the most lascivious, impenitent seducer among your servants…’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Campaign»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Campaign» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Campaign» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.