“Are you telling me that this marvelous girl is really a man in disguise?” said Baltasar, instantly assuming his own vapid, cruel affectation.

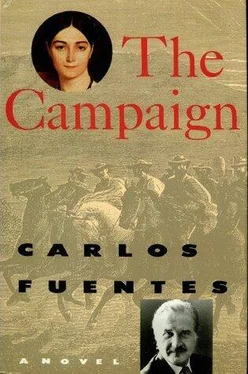

“No”—the priest laughed—“her name is Gabriela Cóo, and her father’s job, an endless, labyrinthine task, is to sell off the Jesuits’ rural properties in Chile for the benefit of the Crown. His daughter is no less emancipated than Rousseau himself, so she works at acting, avidly reading the authors of the age, and communing with nature. Allow me to introduce you, Bustos.”

“Are you telling me that all these afternoons she’s merely been rehearsing a part?” asked Baltasar, plainly disillusioned.

“Pardon me?”

He accepted the invitation to meet her socially, but only under the condition that no one ever find out that each afternoon at five, for as long as he had to live in Chile, he would see her appear, vaporous and infinitely desirable, in the garden next door to his own house. He was afraid that she might already have met him at one of the myriad Santiago gatherings and that she would despise him, as did the other girls, who were, besides, fully aware of his obsession for the vanished Marquise de Cabra. He was just about to reject the introduction and to propose, since both of them were Rousseau enthusiasts, a purely epistolary relationship, like the one in the novel causing a furor throughout the New World, from Mexico to Buenos Aires: La Nouvelle Héloïse.

But three things happened, three foreseeable yet unexpected things. Myopic and foppish, chubby and not very attractive, Baltasar launched into one of an infinite number of dinner conversations with the lady next to him at table. Their dialogue was well under way when Baltasar realized he was acting a romantic part he’d learned perfectly and would recite at these functions. But this role was, at the same time, perfectly authentic, because everything he said corresponded to an intimate conviction, even if its verbal expression was not especially felicitous. This divorce was, simultaneously, the matrimony of his words. He’d repeated them again and again with a mixture of apathy and passion ever since his visit to Lima, searching for Ofelia Salamanca and insinuating that, sentenced to death by the ferocious guerrilla leader Miguel Lanza, he had to place his sympathies with the Crown; after all, the insurgents would deny him any protection whatever.

He could not alter his discourse that night; it was authentic and false at the same time. But he addressed it to her, since he had discovered halfway through dinner that he was speaking to Gabriela Cóo. He gave a face to that face, eyebrows to that visage, a perfume to that body, and now he could not stop the flow of his words, careening like a cart down a mountainside. And each time she answered him in a polite but cutting, intelligent, firm, even amused way, was she laughing at him, as almost all these Chilean girls did who were too beautiful and intelligent to take him seriously? And wasn’t that exactly what he most desired: to be left free to pursue his true passion, the search for Ofelia?

“Whenever I come near to a woman like you, I feel the desire to avenge my pain and my sin on you.”

“You don’t say.”

“Only you can kill the passion in me.”

“It would be a pleasure.”

“I mean: do me the favor of hastening my calvary.”

“To whom are you speaking, Mr. Bustos?”

“I tell you that my soul only wants to recover or die, milady.”

“But I only know how to cure, not to kill.”

“Try to be another woman, and I will not try to seduce you,” said Baltasar, lowering his voice.

“I want neither to be someone else nor to be seduced by you,” she replied in the same low tone, before laughing out loud. “Be more reasonable, Mr. Bustos.”

The second thing that happened was that each afternoon at five she reappeared, far off in her garden. She approached little by little, as if suggesting that she would come closer, allowing herself to be desired, allowing him to make her more and more his own, first in his eyes and his desire and someday perhaps through real possession. The movements of the dance, the increasing languors, the increasing nakedness of that svelte, almost infantile body governed by a mask whose will was a mouth as red as a wound and brows as black as a whip, spelled out her name, Gabriela, Gabriela Cóo, desired, desirable, promising, promised, confident she would not deceive her lover, if he wanted to be her lover, if he gave himself to her, distant and nubile in her garden, as he had given himself to Ofelia Salamanca, distant and widowed, a mother who had given birth twice to the same child, given birth, that is, to life and to death, a woman burdened by suffering and rumors and probable cruelties and imagined betrayals. Gabriela Cóo’s dancing body was asking him to choose but did not say to him, “I am better than the other”; it merely said, “I am different, and you must accept me as I am.”

It had to be that way, Baltasar said to himself every afternoon, because she was no longer rehearsing Rousseau’s play, which was put on just once in the patio of the grand Portuguese-style mansion on Calle del Rey. No longer. Now the performance was for him alone.

She was his little mistress — he decided to give her that name, just as we called him our little brother.

One afternoon, the little brother and the little mistress met without having fixed a time. He jumped over the low wall separating the two properties just as she was coming out of the entrance to her house. Neither yielded, but both gave all. She explained to him that her behavior the other night had not been the infantile act of a spoiled girl trying to entertain in polite society. She really did want to be an actress, she believed in independence — not only political but personal, too. The two went together, at least that is what she believed. Here in Chile, in other parts of the New World, even in Europe, she would pursue her career. She loved words, said Gabriela Cóo; each word had its own life and required the same care as a newborn child. When she opened her mouth, as she did the other night, and repeated a word — love, pleasure, world, sea — she had to take charge of that word like a mother, like a shepherdess, like a lover, yes, even like a little mistress, convinced that, without her, without her mouth, her tongue, the word would smash against a wall of silence and die forsaken.

But to take charge of words that weren’t her own, the words of Rousseau, Ruiz de Alarcón, or Sophocles, she had to prepare herself for a long time. She would give nothing to a man unless he first gave her words. For her, love was a vocation as strong as the theater, but words also sustained love. All this was very difficult, even a little sad — Gabriela Cóo put her arm around Baltasar and patted his curls — because her work was pure shadow, fleeting, left no mark: only the words, poor things, that preceded it were left, and would be, even without her. In order to give meaning to her life of spectral voices, what else could Gabriela think except that, thanks to her mouth, the words had not died but had actually gained a modicum of life, body, dignity, who knows what else?

She felt for Baltasar’s nape under his curly hair and asked if he understood her. He said he did; he knew she understood him equally well. She knew he loved her and why he acted and spoke that way at the Santiago dinners he frequented and why they would be parting soon.

“Tell me it’s not because of that other woman.” Gabriela Cóo thus made her only faux pas, explicable in any case, and he forgave her but decided at that moment to separate her from his life, to give her the freedom she needed, and to give himself to the slavery his obsession with Ofelia entailed until he consummated his passion. At the moment, he could see no other way to be faithful to this adorable girl, Gabriela, Gabriela Cóo, my love, my adored little love, delightful Gabriela; we shall never truly know our own hearts, Little Mistress.

Читать дальше