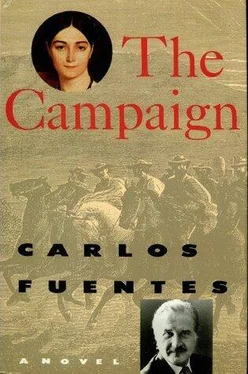

Carlos Fuentes - The Campaign

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carlos Fuentes - The Campaign» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Campaign

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Campaign: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Campaign»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Campaign — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Campaign», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“No one knows you and I are here together.”

“Acla cuna, Acla cuna,” people were shouting in the distance, outside, voices that could be birds calling; the cawing of crows, the screech of some bird of prey. “The chosen one, the chosen one.”

She went back to kneading the cornmeal.

When he wakened, feverish and in the heaviness of a shout, the women were no longer there. The shack was freezing cold. All the fires had gone out. But the clothes dyed purple were scattered over the dirt floor. The man who helped him stand was an old mestizo. He wore a dirty shirt, a frayed tie, blue baize trousers, and hobnail boots. His hair was short, his beard long. He led Baltasar out of the shack and its cold ashes. They were standing in a narrow mountain lane. Baltasar recognized the mountains and smelled the muddy nearness of the lake. The old man led him gently. It was difficult for Baltasar to stay upright, and he leaned on the old mestizo and on the walls made of such smooth, perfectly aligned stones they seemed the labor of titans.

He’d been here a week, but he hadn’t even noticed the most remarkable thing in the place: the architecture, the stones — perfect polygons joined together as if in a magic brotherhood. The discarded, unused stones were called “tired stones,” because they never attained the fraternal embrace of the other polygons.

But only the stones remained. There were no human beings in the streets; no Indians, no creole or Spanish officers, no top-hatted mine owners, no warlords in priestly robes. The micro-republic seemed empty.

“Is anyone left?” asked the astounded Baltasar.

The old man did not appear to hear.

“You wanted to bring these poor people to a mountain peak and show them a limitless empire. From the mountain, they saw an empire that had once been theirs. But it no longer is. They invited you to enter. You did.”

“Damn it! I’m asking you if there is anyone left in this village!” Baltasar Bustos shouted, unable to contain himself. He felt different, speaking in that tone, he who never got angry, he who, when he had to take control of the gauchos, did so with a smile. “Don’t you hear me, old man?”

“No, I don’t hear you. Neither do the people from here.”

“What I said was very clear. Slavery was over, the land will be divided, schools will be built…”

“The Indians didn’t listen to you. For them, you’re just one more arrogant porteño, the same as an arrogant Spaniard, distant, in the end indifferent and cruel. They don’t see the difference. Words don’t convince them. Not even when spoken on horseback.”

“I ordered the priest to implement my edicts.”

“Led by the warlord Ildefonso, they attacked the treasury at Oruro the moment they found out the Spaniards had abandoned the city and before the troops of the other warlord, Miguel Lanza, could arrive. These auxiliary armies exist for themselves, not to serve the Buenos Aires revolution. Fortunately, or unfortunately, it is they who have filled the void between the Crown and the republic. They are here. You merely come, promise things that are never done, and then go.”

“The priest promised to obey the laws,” said Baltasar, obsessed, bewildered.

“There will be time for laws. Eternity can’t be changed in a day. Just think, is Father Ildefonso going to eliminate taxation and the mita while his ally, the Indian leader Pumacusi, thinking that he’s helping him, is assassinating any priest who is not a follower of Ildefonso de las Muñecas? The most urgent item of business is to halt Pumacusi’s excesses. That is, ‘Friends like those make enemies superfluous.’”

The old man stopped in front of a building more luxurious than the others. It must be the town hall, Baltasar thought, trying to identify it as he emerged little by little from his long sleep. The old man — the vain old man — combed out his flowing beard, looking at his face in a windowpane.

“And you, old man, who are you?”

“My name is Simón Rodríguez.”

“What do you do?”

“I teach this and that. My students never forget my teachings, but they do forget me. Woe is me!”

“And the women?” Baltasar Bustos went on asking questions, more to free himself from the old man’s explanations, which said precious little to his fevered mind, than to increase his knowledge of a self-evident fact: Baltasar Bustos knew only one thing, and it was that in his long night, most certainly consisting of many negated days, he had ceased to be a virgin.

“They died, Lieutenant,” said Simón Rodríguez, pausing along with Baltasar in sight of the turbid mountains, the agitated lake, and the empty plaza. “It’s not possible to be an Acla cuna virgin in the service of the ancient gods and sleep with the first petty creole officer who turns up.”

“I didn’t ask…” Baltasar began idiotically, forgetting the exchange of promises with Ildefonso de las Muñecas and then only wanting to say, “I don’t remember anything.” He only wanted to alert himself to something he’d secretly felt when he’d pronounced the liberating edicts at Lake Titicaca, decrees written in the radical rhetoric and the spirit of Castelli but spoken to a people who perhaps had their own roads to liberty, not necessarily — Baltasar wrote in a letter sent both to Dorrego and to me — those we have piously devised:

When, surrounded by the physical desolation of the plateau and looking into the unflinching faces of the Indians, I read our proclamations, I felt a terrible temptation, which perhaps was the only one the Devil himself could never resist. I felt the temptation to exercise power with impunity over the weak. I wanted to impose my laws, my customs, my fears, and my temptations on them, even though I knew that they do not have, for the time being, any means to answer me. I wanted to see myself at that moment, astride my horse, with my three-cornered hat in one hand and the proclamation in the other, transformed into a statue. That is, dead. And something worse, my friends. For a moment I felt mortally proud of my superiority, and at the same time in love with the inferiority of others. I knew of no other way to relieve my pride than through an immense tenderness and a huge shame as I dismounted to touch the heads of those who respected me merely for my tone of voice even though they understood not a word of what I’d read them.

But Simón Rodríguez went on talking. “She was supposed to grow old a virgin. It was her vow, and she broke it for you.”

“Why?” Baltasar asked again furiously — without recognizing himself — before he wrote us the letter and before he found something of an answer in the very fact of asking why.

“You entered this place without knowing it. You spoke to these people from a mountaintop. Now you must descend to the poor land of the Indians. It is land that has been subjugated by the laws of poverty and slavery. But it is also a land liberated by magic and dreams…”

“Where are you taking me?” asked Baltasar, whose intelligence informed him that here in this abandoned village on the shore of the lake, he had no alternative but to follow.

Simón Rodríguez, with a strength that was supernatural in a man his age, first clasped Baltasar’s arms and then his shoulders, turning him to face the windowpane. Finally, he grasped the nape of the young Argentine military man’s neck, forcing him to see himself in the window where just a few minutes earlier the old man had combed his beard.

Baltasar, examining himself, saw a different man. His mane of copper-colored curls had grown. The fat had gone from his face. His nose grew sharper by the moment. His mouth became firmer. His eyes, behind his glasses, revealed a rage and a desire where before they had only seemed good-natured. His beard and mustache had grown. With this face he could look on the world in a different way. He didn’t say it. He merely asked himself again. He was no longer a virgin — a boy, as that strange priest de las Muñecas insisted on calling him. For whom had he been a virgin? Not for Ofelia Salamanca, whom he’d only seen and loved from a distance, three years ago. Did his tranquil passion to save himself for a woman have any other objective? Was there another, one who wasn’t Ofelia or the Indian virgin who had violated her vows to give herself to him? What are we doing here on this earth? Jean-Jacques had asked himself. “I was brought to life, and I’m dying without having lived.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Campaign»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Campaign» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Campaign» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.