Jonathan Franzen - The Discomfort Zone

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jonathan Franzen - The Discomfort Zone» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Ney York, Год выпуска: 2006, ISBN: 2006, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Discomfort Zone

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2006

- Город:Ney York

- ISBN:918-0-312-94841-2

- Рейтинг книги:3.5 / 5. Голосов: 2

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Discomfort Zone: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Discomfort Zone»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Notable Book of the Year The Discomfort Zone

The Discomfort Zone — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Discomfort Zone», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

To get to the main roof, you climbed a long, sturdy downspout near the music rooms, crossed a plain of tar and caramel-brown Missouri gravel, and climbed a metal staircase and a sheer eight-foot wall. Unless you were me, you also had to stop and drag me up the eight-foot wall. The growth spurt I’d had the year before had made me taller and heavier and clumsier, while leaving unaltered my pitiful arm and shoulder strength.

I was probably nobody’s idea of an ideal fellow gang member, but I came with Manley and Davis, my old friends, who were good athletes and avid climbers of public buildings. In junior high, Manley had broken the school record for pull-ups, doing twenty-three of them. As for Davis, he’d been a football halfback and a starting basketball forward and was unbelievably tough. Once, on a January campout in a deserted Missouri state park, on a morning so cold we split our frozen grapefruits with a hatchet and fried them on an open fire (we were in a phase of cook-it-yourself fruitarian-ism), we found an old car hood with a towrope attached to it, irresistible, irresistible. We tied the rope to our friend Lunte’s Travelall, and Lunte drove at ill-considered speeds along the unplowed park roads, towing Davis while I kept watch from the back seat. We were doing about 40 when the road plunged unexpectedly down a hill. Lunte had to brake hard and steer into a skid to avoid rolling the Travelall, which cracked the towrope like a whip and flung Davis at a sick-making velocity toward a line of heavy-duty picnic tables stacked up in falling-domino formation. It was the kind of collision that killed people. There was a sunlit explosion of sparkling powder and shattered lumber, and through the rear window, as the snow settled and Lunte slowed the vehicle, I saw Davis come trotting after us, limping a little and clutching a jagged shard of picnic table. He was shouting, he said later, “I’m alive! I’m alive!” He’d demolished one of the frozen tables — knocked it into a hundred pieces — with his ankle.

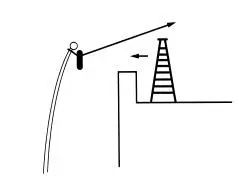

Also dragged to the roof, along with me, were the stepladder, lots of rope, two bald steel-belted radials, and the Device that Davis and I had built. Leaning out over the balustrade, we could sort of almost touch the flagpole. The object of our fixation wasn’t more than twelve feet away from us, but its skin of aluminum paint matched the cloudy bright suburban sky behind it, and it was curiously hard to see. It seemed at once close and far away and disembodied and very accessible. The six of us stood there wishing we could touch it, groaning and exclaiming with desire to touch it.

Although Davis was a better mechanic, I was more facile than he at arguing for doing things my way. As a result, little we built ever worked. Certainly our Device, as soon became apparent, had no chance. At the end of the board was a crude wooden bracket that could never have gripped the flagpole, especially under the added weight of a tire; there was also the more fundamental difficulty of leaning out over a balustrade and pulling hard on a heavy board to control it while also trying to push it against a flagpole that, when bumped, clanged and swung distressingly. We were lucky not to send the Device through one of the windows on the floors below us. The group verdict was swift and harsh: piece of shit .

I laughed and said it, too: piece of shit . But I went off to one side, my throat thick with disappointment, and stood alone while everybody else tried the lasso. Peppel was swinging his hips like a rodeo man.

“Yee haw!”

“John-Boy, gimme that lasso.”

“Yee haw!”

Over the balustrade I could see the dark trees of Webster Groves and the more distant TV-tower lights that marked the boundaries of my childhood. A night wind coming across the football practice field carried the smell of thawed winter earth, the great sorrowful world-smell of being alive beneath a sky. In my imagination, as in the pencil drawings I’d made, I’d seen the Device work brilliantly. The contrast between the brightness of my dreams and the utter botch of my executions, the despair into which this contrast plunged me, was a recipe for self-consciousness. I felt identified with the disgraced Device. I was tired and cold and I wanted to go home.

I’d grown up amid tools, with a father who could build anything, and I thought I could do anything myself. How difficult could it be to drill a straight hole through a piece of wood? I would bear down with the utmost concentration, and the drill bit would emerge in a totally wrong place on the underside of the wood, and I would be shocked. Always. Shocked. In tenth grade I set out to build from scratch a refracting telescope with an equatorial mount and tripod, and my father, seeing the kind of work I was doing, took pity on me and built the entire thing himself. He cut threads in iron pipe for the mounting, poured concrete in a coffee can for the counterweight, hacksawed an old carbon-steel bedframe for the base of the tripod, and made a cunning lens mount out of galvanized sheet metal, machine screws, and pieces of a plastic ice-cream carton. The only part of the telescope I built on my own was the eyepiece holder, which was the only part that didn’t work right, which rendered the rest of it practically useless. And so I hated being young.

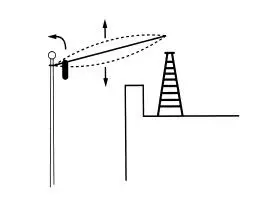

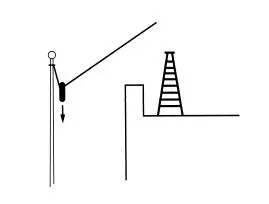

It was after one o’clock when Peppel finally threw the lasso high and far enough to capture the flagpole. I stopped sulking and joined in the general cheering. But new difficulties emerged right away. Kortenhof climbed the stepladder and tugged the lasso up to within a foot of the ball, but here it snagged on the pulley and flag cables. The only way to propel a tire over the top would be to snap the rope vigorously up and down:

When we strung the tire out on the rope, however, it sagged out of reach of the top:

To raise the tire, Kortenhof had to pull hard on the rope, which, if you were standing on a ladder, was a good way to launch yourself over the balustrade. Four of us grabbed the ladder and applied counterforce. But this then wildly stressed the flagpole itself:

The flagpole made worrisome creaking and popping sounds as it leaned toward us. It also threatened, in the manner of a strained fishing rod, to recoil and cast Kortenhof out over Selma Avenue like a piece of bait. We were thwarted yet again. Our delight in seeing a tire rubbing up against the desired ball, nudging to within inches of the wished-for penetration, only heightened our anguish.

Two months earlier, around the time of her fifteenth birthday, my first-ever girlfriend, Merrell, had dumped me hard. She was a brainy Fellowship girl with coltish corduroy legs and straight brown hair that reached to the wallet in her back pocket. (Purses, she believed, were girly and antifeminist.) We’d come together on a church-membership retreat in a country house where I’d unrolled my sleeping bag in a carpeted closet into which Merrell and her own sleeping bag had then migrated by deliriously slow degrees. In the months that followed, Merrell had corrected my most egregious mannerisms and my most annoying misconceptions about girls, and sometimes she’d let me kiss her. We held hands through the entirety of my first R-rated movie, Lina Wertmüller’s Swept Away , which two feminist advisors from Fellowship took a group of us to see for somewhat opaque political reasons. (“Sex but not explicit,” I noted in my journal.) Then, in January, possibly in reaction to my obsessive tendencies, Merrell got busy with other friends and started avoiding me. She applied for transfer to a local private academy for the gifted and the well-to-do. Mystified, and badly hurt, I renounced what Fellowship had taught me to call the “stagnation” of romantic attachments.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Discomfort Zone»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Discomfort Zone» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Discomfort Zone» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.