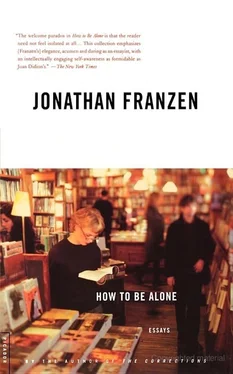

HOW TO BE ALONE

Jonathan Franzen

My third novel, The Corrections , which I’d worked on for many years, was published a week before the World Trade Center fell. This was a time when it seemed that the voices of self and commerce ought to fall silent — a time when you wanted, in Nick Carraway’s phrase, “the world to be in uniform and at a sort of moral attention forever.” Nevertheless, business is business. Within forty-eight hours of the calamity, I was giving interviews again.

My interviewers were particularly interested in what they referred to as “the Harper’s essay.” (Nobody used the original title, “Perchance to Dream,” that the magazine’s editors had given it.) Interviews typically began with the question: “In your Harper’s essay in 1996, you promised that your third book would be a big social novel that would engage with mainstream culture and rejuvenate American literature; do you think you’ve kept that promise with The Corrections ?” To each succeeding interviewer I explained that, no, to the contrary, I had barely mentioned my third novel in the essay; that the notion of a “promise” had been invented out of thin air by an editor or a headline writer at the Times Sunday Magazine; and that, in fact, far from promising to write a big social novel that would bring news to the mainstream, I’d taken the essay as an opportunity to renounce that variety of ambition. Because most interviewers hadn’t read the essay, and because the few who had read it seemed to have misunderstood it, I became practiced at giving a clear, concise précis of its argument; by the time I did my hundredth or hundred-tenth interview, in November, I’d worked up a nice little corrective spiel that began, “No, actually, the Harper’s essay was about abandoning my sense of social responsibility as a novelist and learning to write fiction for the fun and entertainment of it. .” I was puzzled, and more than a little aggrieved, that nobody seemed able to discern this simple, clear idea in the text. How willfully stupid, I thought, these media people were!

In December I decided to pull together an essay collection that would include the complete text of “Perchance to Dream” and make clear what I had and hadn’t said in it. But when I opened the April 1996 Harper’s I found an essay, evidently written by me, that began with a five-thousand-word complaint of such painful stridency and tenuous logic that even I couldn’t quite follow it. In the five years since I’d written the essay, I’d managed to forget that I used to be a very angry and theory-minded person. I used to consider it apocalyptically worrisome that Americans watch a lot of TV and don’t read much Henry James. I used to be the kind of religious nut who convinces himself that, because the world doesn’t share his particular faith (for me, a faith in literature), we must be living in End Times. I used to think that our American political economy was a vast cabal whose specific aim was to thwart my artistic ambitions, exterminate all that I found lovely in civilization, and also rape and murder the planet in the process. The first third of the Harper’s essay was written from this place of anger and despair, in a tone of high theoretical dudgeon that made me cringe a little now.

It’s true that, even in 1996, I intended the essay to document a stalled novelist’s escape from the prison of his angry thoughts. And so part of me is inclined now to reprint the thing exactly as it first appeared, as a record of my former zealotry. I’m guessing, though, that most readers will have limited appetite for pronouncements such as

It seemed clear to me that if anybody who mattered in business or government believed there was a future in books, we would not have been witnessing such a frenzy in Washington and on Wall Street to raise half a trillion dollars for an Infobahn whose proponents paid lip service to the devastation it would wreak on reading (“You have to get used to reading on a screen”) but could not conceal their indifference to the prospect.

Because a little of this goes a long way, I’ve exercised my authorial license and cut the essay by a quarter and revised it throughout. (I’ve also retitled it “Why Bother?”) Although it’s still very long, my hope is that it’s less taxing to read now, more straightforward in its movement. If nothing else, I want to be able to point to it and say, “See, the argument is really quite clear and simple, just like I said!”

What goes for the Harper’s essay goes for this collection as a whole. I intend this book, in part, as a record of a movement away from an angry and frightened isolation toward an acceptance — even a celebration — of being a reader and a writer. Not that there’s not still plenty to be mad and scared about. Our national thirst for petroleum, which has already produced two Bush presidencies and an ugly Gulf War, is now threatening to lead us into an open-ended long-term conflict in Central Asia. Although you wouldn’t have thought it possible, Americans seem to be asking even fewer questions about their government today than in 1991, and the major media sound even more monolithically jingoistic. While Congress yet again votes against applying easily achievable fuel-efficiency standards to SUVs, the president of Ford Motor Company can be seen patriotically defending these vehicles in a TV ad, avowing that Americans must never accept “boundaries of any kind.”

With so much fresh outrageousness being manufactured daily, I’ve chosen to do only minimal tinkering with the other essays in this book. “First City” reads a little differently without the World Trade Center; “Imperial Bedroom” was written before John Ashcroft came to power with his seeming indifference to personal liberties; anthrax has lent farther poignancy to the woes of the United States Postal Service, as described in “Lost in the Mail”; and Oprah Winfrey’s disinvitation of me from her Book Club makes the descriptive word “elitist” fluoresce in the several essays where it appears. But the local particulars of content matter less to me than the underlying investigation in all these essays: the problem of preserving individuality and complexity in a noisy and distracting mass culture: the question of how to be alone.

[2002]

Here’s a memory. On an overcast morning in February 1996, I received in the mail from my mother, in St. Louis, a Valentine’s package containing one pinkly romantic greeting card, two four-ounce Mr. Goodbars, one hollow red filigree heart on a loop of thread, and one copy of a neuropathologist’s report on my father’s brain autopsy.

I remember the bright gray winter light that morning. I remember leaving the candy, the card, and the ornament in my living room, taking the autopsy report into my bedroom, and sitting down to read it. The brain (it began) weighed 1,255 gm and showed parasagittal atrophy with sulcal widening . I remember translating grams into pounds and pounds into the familiar shrink-wrapped equivalents in a supermarket meat case. I remember putting the report back into its envelope without reading any further.

Some years before he died, my father had participated in a study of memory and aging sponsored by Washington University, and one of the perks for participants was a postmortem brain autopsy, free of charge. I suspect that the study offered other perks of monitoring and treatment which had led my mother, who loved freebies of all kinds, to insist that my father volunteer for it. Thrift was also probably her only conscious motive for including the autopsy report in my Valentine’s package. She was saving thirty-two cents’ postage.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу