Fig. 3.4. “R2-D2, Halloween, 1988”

Pasted into R. Radmanovic’s Little Rule Book of Life

Exhibit C:

In the Kearny High School faculty meeting minutes dated November 1, 1990, chemistry teacher Emily Gagnon relates an incident of “bullying” that took place at the school on Halloween. The details are hard to fully make out from the meeting’s rather perfunctory notes, but it appears that sophomore Radar Radmanovic, dressed “again” in a tinfoil R2-D2 costume, was “found by a member of [the] janitorial staff” trapped in a “dumpster behind [the] gymnasium.” When pressed for details, Mr. Radmanovic would not elaborate on how he had gotten there. The incident led to a larger discussion at the meeting about bullying at the school, with a host of faculty members chiming in on the perceived severity of the problem. Perhaps most troubling was Ms. Gagnon’s comment, recorded in the minutes, that this was “not [the] first time [we’ve found] Radar in [the] dumpster.”

Exhibit D:

On the afternoon of December 5, 1990, a varsity basketball game inside the Kearny High School gymnasium was interrupted when both teams and the majority of the three dozen spectators experienced what was described in the police report as “cramping” and “diarrhea-like symptoms.” This turns out to be polite language for what was in essence a mass crapping of the pants. A barrage of ambulances and even a P3 CDC hazmat team from Long Island were summoned, and rumors of a “killer virus” whipped through the community like wildfire, but doctors could find nothing wrong with the victims beyond a lasting case of public humiliation and a newfound appreciation for the daily operations of the lower intestine. Curiously, none of the city’s tabloids carried the story, ignoring a golden opportunity for near-infinite scatological punnage. Only WWOR-TV, a local outfit broadcasting from Secaucus, mentioned the incident, briefly, during its evening newscast — and even they neglected to dispatch an on-scene reporter. Neither they nor anyone else, apparently, looked into the possibility of the so-called infrasonic “brown note,” rumored to be somewhere around 22.275 Hz, effective when broadcast at levels of at least 120 decibels. The elusive brown note was purportedly experimented with by the French during World War II and is currently used by certain elite Japanese SWAT teams, although there has never been any official documentation of its effective implementation. Nor did anyone bother to interview Radar Radmanovic, the installer and student operator of Kearny High School’s highly sophisticated (some might say excessive) public address system, who also happened to be working the scoreboard for the game that afternoon.

Fig. 3.5. Sample Tests, KHS Gymnasium PA System (March 1990)

From Notebook of R. Radmanovic

Exhibit E:

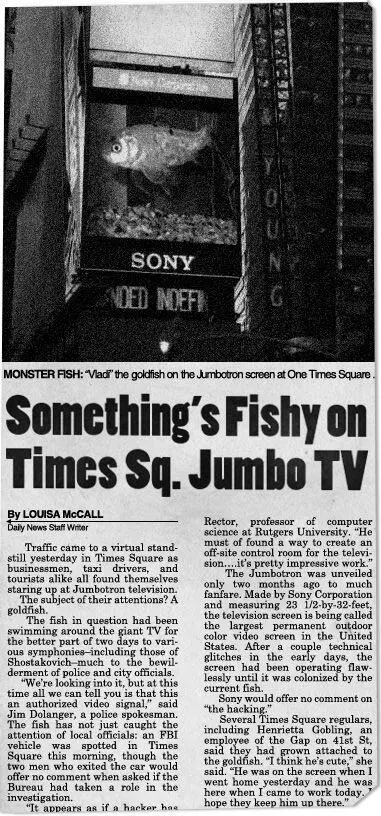

Finally, there is the now mostly forgotten “Vladi Affair” from December of that same year. Those living in New York City at the time may remember that for a series of three consecutive days right in the middle of the Christmas rush, the newly installed Sony Trini-lite JumboTron at One Times Square displayed a strange series of interference patterns — including clips from 3-2-1 Contact and various Run-D.M.C. music videos, but most famously a grainy feed of a mildly beleaguered goldfish with a black spot on its forehead, swimming in circles to Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7 (“Leningrad”), which played from a hidden speaker that would take the authorities a day and a half to locate. The iconic image of this fish limping to moribund Soviet nostalgia persisted for almost seventy-two hours, evading the best efforts of the JumboTron’s engineers to correct the malfunction. A December 17 New York Daily News article surmised that some “hacker” (an early use of the term, at least for the Daily News ) had managed to create an “off-site remote control” and taken command of the television, despite the fact that the screen was not actually connected to any VHF or cable receiver system but instead received its data from prerecorded LP-size “optical discs.” The Daily News noted that the goldfish had already caused “several car accidents” and that the NYPD, Port Authority, and the FBI were all investigating the crime. On the fourth day, the giant screen at the junction of Broadway and Seventh Avenue was unplugged, an act that met with some popular outcry, as the goldfish — by this point nicknamed “Vladi” by a popular on-air personality — had gained a cultish following among commuters and tourists alike, perhaps buoyed by the recent dramatic fall of Communism. When the JumboTron was finally turned on again two days later, the interference patterns had ceased and did not resume again, though it is debatable whether this was because the JumboTron’s engineers had discovered a way to block the incoming transmissions or whether “the hacker” had ceased his malicious activity. Regardless, the crime remained unsolved. Years later, you could still find certain street kiosks selling T-shirts of the goldfish’s pixelated image, with the caption VLADI LIVES! printed in some heavy-handed pseudo Soviet font.

Fig. 3.6. “Something’s Fishy on Times Sq. Jumbo TV”

From New York Daily News, Dec. 17, 1990

Of course, if the authorities had checked the attendance sheet for Kearny High School, they would have discovered that Radar Radmanovic had been absent from school on the three consecutive days of the JumboTron’s disruption. There also exists a photograph of Radar sitting at his home-brewed ham radio station in his bedroom, giant ear cans on his head, delivering an enthusiastic thumbs-up to the camera. In the background, perched precariously on a transceiver, a mildly beleaguered goldfish is clearly visible. The goldfish matches — in demeanor and appearance, including the single black spot — the famous Vladi, though on the back of the photograph Radar has written R.I.P. DOBROFISH, suggesting that the fish was named for Dobroslav Radmanovic´, the man responsible for bringing their family to the New World before collapsing in a grocery store checkout line, ground chuck in hand.

Other items from the R. Radmanovic file seem important to highlight: Radar graduated from Rutgers, although, due to an apparent computer glitch, he actually graduated twice (if on paper only), with a dual degree in religious studies and electrical engineering, summa cum laude each time, making him the most decorated undergraduate in the history of that school. Such illustrious qualifications landed him a job directly out of college as the WCCA Belleville Transmission Site assistant manager of operations. Now, after thirteen years of exemplary work, he was head engineer of transmission. During that time he had been named employee of the month fourteen times for the Green Channel Network, a midsize regional media conglomerate that spanned the tri-state area as well as parts of western Massachusetts. No other employee had received the honor more than twice. And yet, once he had become master of the transmission site, Radar had not moved up in the corporate hierarchy, despite repeated offers of upper-level management positions. Eventually, the GCN executives had simply stopped trying. Apparently their savant engineer preferred to stay where he was, in the swamps, conjuring signal.

Читать дальше