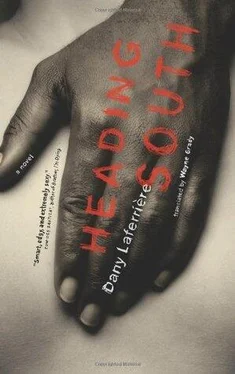

The next day Mauléon again takes up his seat on the side of the road and continues his reflections. He knows full well that the solution will have to come from his head, since he has nothing whatsoever in his pockets. Strange that he could come safe and sound from the worst jungle in the world— the Bronx, where he spent the last two years of his New York exile — only to die of boredom on the shores of Gressier. In the Bronx, one moment of inattention could earn you a bullet in the back of the head; here it’s boredom that’ll skin a man alive. If you have nothing to do here, you’d better invent something quick, or else long siestas, alcohol or malaria will bring you down. Mauléon is still sitting there when he notices a curious exchange taking place a hundred metres down the road: sitting on the porch of another hotel is a woman who appears to be in her fifties, sipping a coloured drink, when a young man of sixteen or seventeen crosses the sun-drenched road and approaches her table. They talk for several minutes, then the barman comes out and tells the youth to leave the porch. The young man rises politely and makes to leave, but the woman, a guest of the hotel (which is known as a gathering place for people from Quebec) says something to the barman and the young man sits back down. However, they don’t stay for long. The woman empties her glass, picks up her handbag, and the two of them head off towards the beach.

Mauléon watches them for a moment as they enter the water. The woman is tall and elegant. The young man is neither particularly handsome nor well muscled. A relaxed couple. What interests Mauléon is that they didn’t head straight off to one of the rooms, but went instead to the sea. The sea that knows no age. In the presence of that turquoise eternity, fifty years is not that far from seventeen. Playing in the water makes you young once more. As young as the world. Mauléon waits for a while before going over to speak to the barman. He finds the man standing on a table, changing a light bulb. He, too, is in his fifties, self-assured and a bit taken with himself.

“That couple who just left?”

Yes, of course he knows them.

“The boy came up from Port-au-Prince about two years ago. His name is Legba. He comes from the Cap, same as me. The sea puked him out one morning, and I took him in. He was as thin as a rail. I fed him, looked after him like I would any other wounded bird that washes up on the beach. That’s the way I am. Every morning I ask myself what the sea is going to bring me today.”

“Yes, but getting back to Legba. .” says Mauléon.

“I sent him to school to learn English, which he picked up in the blink of an eye. He’s a bright kid, highly intelligent. I hoped he’d continue his studies, but he went in for hard drugs and easy money, the sea, which he knows well, and forbidden fruit. I don’t mind admitting that he disappoints me. That’s why I don’t let them hang around here. There’s a whole gang of them in these parts. Mostly they come from Cité Soleil, that shantytown you can see across the bay there. . They’re pests. .”

“And the woman?”

“She’s from Quebec. . When they get cold up there they come down south to get warm. It doesn’t cost an arm and a leg, and every day is sunny. They come for a week or two and stay for a month, two months, even six months. . And every year they come back.”

“Why?”

The barman leers at him.

“Because of them,” he says, pointing to a group of young men horsing around on the beach.

Mauléon watches them for a while (their young, supple bodies, their crazy laughter, their childish games). Children of the sun god. He suddenly feels as though a light has been turned on in his head. He quickly says goodbye to the barman. “That’s just what I need,” he tells himself when he is back on the road. He won’t ban those magic boys from his hotel, he’ll put up with them, he’ll welcome them, he’ll even invite them. They’re a real gold mine.

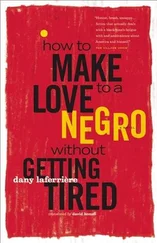

THERE THEY are, hanging around the bar down by the beach.

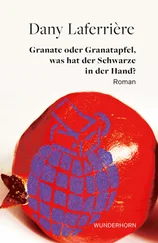

“A ham sandwich and a glass of pomegranate juice,” Gogo calls out.

“Same for me,” says Chico, “but make mine a real thick sandwich, Albert. . I had a hard night last night and I need to regain my strength. . Okay?”

The barman says nothing.

“Ah, don’t be like that, Albert,” Mario teases. “Everything’ll be all right. . This is better than being in jail, isn’t it? Nothing to complain about. . Give us a smile, just a little one. . You know, I’ve never seen Albert smile. .”

“What would you like?” Albert says to him archly.

“All right, Albert, you win. No smile today, either. . So, I’ll have a malted, lots of ice. . I have to go up to Number Eight in a few minutes.”

“Ah, you’re doing Mrs. Wenner this morning!” Chico cries merrily. Chico is always in a good mood.

“She’s a real hard nut to crack,” says Gogo. “Hey, Albert! I said a cheese sandwich. You know I can’t stand ham, it upsets my stomach. . He does it on purpose, I swear. .”

“Let him alone,” says Mario.

“Gogo’s right, Albert,” Chico says, laughing. “He ordered a ham sandwich; I was there.”

“Stop it, Chico,” says Gogo, “you’re going to drive the poor man crazy. .”

“Hey, guys!” says Mario. “I’ve got to go up to Number Eight; someone give me some pointers. . And you, Gogo, don’t play the same trick on me today that you did yesterday. .”

“What’d he do?” asks Chico.

“He told me that Mrs. Woodroff was a former nun and I had to fuck her from behind while saying the Lord’s Prayer if I wanted to make her come. .”

“Jesus! You’re not even supposed to touch her,” says Mario.

“She’s not as bad as Mrs. Hopkins,” throws in Chico, seriously, “the widow in Number Six. She spent three hours talking to me like I was her son before jumping my bones.”

“I’ve already done her,” says Gogo. “It must have been the first time in her life that she found herself alone in a room with someone who wasn’t her husband.”

“She must have been shy,” Mario says.

“Maybe at first, but after a few minutes it was clear she knew exactly what she wanted. .”

“She reminds me of Madame Bergeron,” says Gogo.

“Who’s that?” asks Chico.

“You remember her, the one who went around introducing herself by shouting, ‘I’m Madame Bergeron from Boucherville. Do you know Boucherville?’”

“Oh, her. Now I remember,” says Chico. “Why bring her up?”

“It would be like being in a restaurant with her,” says Gogo, “with her giving her opinion about everything, every minute detail, making sure the meat they served was top quality, the vegetables fresh, the napkins clean, and so on.”

“Oh, yeah, I remember now,” says Chico, laughing. “She’d go: ‘Lower, no, lower. . Now higher. . A little to the right. . There! Now get back on, get back on, but gently, oh gently. . No, my breasts, keep on massaging my breasts. . Where are your hands? What are they doing? You should be using them. . Now go hard, harder, as hard as you can. . That’s it, as hard as you can!’—she’d say that a little scornfully—‘Softer. . Softly. . Use your tongue, too. . Ah, there, now you can do what you want, I’m going to come. .’”

The others watch Chico and Gogo mimicking the scene under the intensely disapproving eye of Albert.

“You can laugh if you want, Albert,” says Gogo. “They won’t make you pay for it, you know.”

“I know he laughs,” says Chico. “He’s laughing on the inside. I’ll bet he tells our stories to all his friends.”

Albert’s implacable face.

“All this talk, and I still don’t know what I’m supposed to do with Mrs. Wenner. I have to go up there in a few minutes. .”

Читать дальше