“Now,” says Carl-Henri, “it’s just so much meat. .”

“What happened between then and now?” asks the journalist, intrigued.

“Ah, that you’ll have to ask Jacques.”

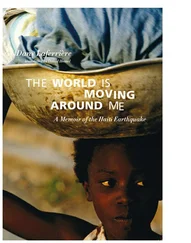

Jacques Gabriel settles himself behind the wheel. The journalist wisely decides not to question him about the goat. We drive for ten or fifteen minutes before turning left onto a redochre road that climbs fairly steeply up a slope and ends at a small shack with a thatched roof.

“Everyone out,” says Jacques Gabriel. “This is where my friend the Prophet lives. . Wait here, I’ll go in first.”

We wait for ten or fifteen minutes and then Gabriel comes out accompanied by a tall man with a grave expression on his face.

“This is my friend the Prophet. He’s a great painter. . Blessed by the gods of voodoo. . He dwells in the depths where gods speak directly to men. .”

The Prophet smiles. A smile of infinite sadness.

“I knew you were coming,” he says simply, then turns and goes back towards his house.

Jacques Gabriel gets the goat and gives it to a young man who has appeared suddenly among us. The young man takes it and vanishes as swiftly as he appeared.

“The Prophet’s working,” says Jacques Gabriel. “He’s making a painting to celebrate our arrival. He’ll join us later.”

The young man comes back with a few straw chairs that he arranges in a semicircle on the verandah. While he’s at it, I see an enormous woman passing, accompanied by a dozen young girls in white robes with their heads wrapped in white kerchiefs.

“The Prophet is first and foremost a voodoo priest,” Jacques Gabriel explains. “He started painting by making an altar to attract the gods. One day a man named DeWitt Peters, an American who was into Haitian painting, came by, and spent the whole day looking at the portraits of voodoo gods that the Prophet had painted on the walls of his house, and in the end came to the conclusion that the Prophet was the most authentic artist he had ever encountered.”

“How does that differentiate him from you?” asks the journalist, who has just remembered she has to write an article about Jacques Gabriel.

Gabriel drags a chair closer to the door and sits down. This is going to take a while.

“The Prophet isn’t his real name. . He’s been called that since he was nine years old. He was living in Dondon, a commune near Saint-Raphaël, with his mother and his younger sister. His father had left to cut cane in the Dominican Republic. At that time he still hadn’t learned to talk. He couldn’t read or write. When he wanted to tell someone something, he drew it.”

“Interesting,” says the journalist, “but not particularly unique.”

“He has another gift. He can draw the future.”

“How’s that again?” I ask.

Jacques Gabriel smiles. The fish has taken his bait.

“One day he comes home from school. His mother is making dinner. He refuses to touch the food. He takes out his pocketknife and draws a headless man lying on a large mahogany table. His mother is amazed. ‘It’s my father,’ he says simply. An hour later a messenger arrives with the news that his father is dead. ‘How did he die?’ the mother asks. She’s told that there was a violent argument with another worker in a canefield at San Pedro de Macorís, and that the other man cut off the father’s head with a single swipe of his machete. A week later, the boy draws a house in flames. That same night a fire completely destroys the house next door. Another time he draws his cousin with a single leg. The cousin lived in Saint-Raphaël. The next day his leg gets caught in a piece of mill machinery and has to be cut off to prevent the rest of the body from being pulled in. The mother refuses to allow the boy to do any more drawings. Then one morning, before going to the Ranquitte market to sell her vegetables, the mother says to him, ‘Why don’t you draw any more pictures?’ To which the boy replies, ‘But Mama, you told me I couldn’t!’ ‘Ah, yes, I forgot! Make me a drawing now.’ So the boy goes into the house and makes the drawing. When he comes back out, she has already left for the market. The drawing shows a woman lying in a coffin. After her death, the villagers in Dondon start calling him the Prophet. He’s travelled pretty much all over the country, but eventually settled here in Croix-des-Bouquets. He serves his gods, lives with these women, indifferent to fame. His art is celebrated the world over. So that’s the Prophet, the only completely free man I know.”

“Why is that?” Carl-Henri asks, almost timidly.

“Well! Every time he takes up a paintbrush he knows that he might be about to paint his own death scene, and yet his hand never trembles.”

The young man comes out with a large bowl balanced on his head. Behind him come the girls, in single file, with the large woman bringing up the rear. He sets the bowl down among us. It is filled with food — goat stew, peeled bananas, white rice, yams, breadfruit, carrots, beets, eggplant and cream sauce.

“No utensils!” Jacques Gabriel cries delightedly. “We eat with our fingers, our good old fingers. .”

Brief silence.

“Won’t it be too hot?” asks the journalist.

“It’ll be fine!” says Gabriel, plunging his hand into the middle of the bowl.

That’s the signal. We are all, it seems, famished.

I don’t know if it’s all these happenings, or the strange atmosphere (the starless night, the light breeze, the distant beating of a drum), the tender flesh of the goat (was it an animal or something else entirely?), or the subtle aroma of the yams, the taste for breadfruit that I definitiely thought I’d lost. . Or maybe it’s the combination of all of it that makes me think this is the best meal I have ever had in my life. I once saw on television (the usual scene) a family of lions devouring a young antelope. When they were finished there was nothing left but white bones, without a trace of flesh left on them.

We can see the bottom of the bowl before we know it. At the same moment, a song splits the air. I can see the young man’s throat swelling and deflating, like a lizard’s. A formless emotion grips my heart. I feel as though I’m in another world. Somewhere far from Pétionville and its mundane concerns. The young man is leaning against a post and singing about a woman from Artibonite whose husband (Solé or Soleil or something) is gravely ill. A choir of young voices accompanies the woman in her distress. The man hovers between life and death, between night and day. But the woman is brave, she fights to save her man. Then the young man goes on to sing several folk songs that tell about the misery of peasants’ lives.

Suddenly there is a sacred song: “Papa Legba ouvri baryé pou mwen. .” I sense a new energy flowing from the choir. The girls’ voices climb higher and higher, as though announcing the arrival of an eminent personage. In fact it’s the Prophet, who has just appeared at the door (as the Prophet, or Legba) wearing ceremonial robes. His face is even graver than it was at our arrival. The voices reach their highest pitch and then descend slowly into silence.

“The painting is finished,” the Prophet says laconically, making a sign to the young man to bring it out.

The fat woman begins to dance, although there is no music. We hear only the heavy sound of her bare heels on the ground. Suddenly she breaks into a sacred chant. A warrior’s chant, although I can’t make out the words. Most of them seem to be of African origin. Her flesh ripples. She scowls menacingly. The Prophet follows her with his eyes, looking vaguely disturbed. A terrible god is knocking at the door. He cannot break into our circle. Suddenly the woman slumps down in a corner, exhausted. She looks like an unstrung marionette. The audience breathes. Ogou, the terrible god of fire, couldn’t spoil the party. The young man comes out carrying the Prophet’s painting. It is covered with a mauve cloth. One of the young girls comes over and removes the cloth, and the magnificent but terrifying painting is revealed to us. All in mauve. The Prophet’s colour. The figures and their surroundings are all mauve. All of us are in the painting. The young man, the girls in their white robes, the fat woman in mauve, the little prostitute, Carl-Henri and me. There are three figures at the centre: the Prophet in the middle, Jacques Gabriel on his left and the journalist, wearing a white wedding gown, on his right. The girl who uncovered the painting goes over to the journalist and drapes the mauve cloth over her head. All the blood has drained out of the Parisian journalist’s face.

Читать дальше