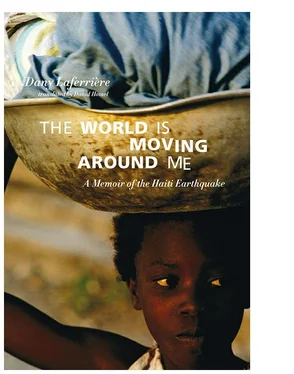

Dany Laferriere

I Am a Japanese Writer

For the little group at the Hôtel Karibe

who faced the wrath of the gods with me:

Michel Le Bris, Maëtte Chantrel, Mélani Le Bris,

Isabelle Paris, Agathe du Bouäys,

Rodney Saint-Éloi, and Thomas Spear

In the face of death

There should be neither joy nor sadness

Just a long astonished gaze

— Renaud Longchamps

The Right Honourable Michaëlle Jean

Special Envoy for Haiti for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, and former Governor General of Canada

The “Étonnants voyageurs” international festival of books and film was about to take place in Haiti in January 2010 when, suddenly, all hell broke loose. The deadliest earthquake in the country’s history threw the nation into shock and horror.

Dany Laferrière was among the novelists, poets, and publishers staying at the Hôtel Karibe, overlooking the city of Port-au-Prince.

Not only did the ground beneath their feet betray them, as the earth let loose a deafening growl, but words failed them when it came time to describe that moment of truth, when brutal reality left the voice of fiction speechless.

The only solid things that remained in their lives were those everyday actions that helped them hold onto what had collapsed: the few landmarks still standing amid an inferno of rubble; the few loved ones left among the survivors, who were themselves damaged, riddled with cracks.

Dany Laferrière, faithful guardian and watchman, would work to recover his senses and his stability in the face of this catastrophe and try to make meaning of it.

One day he wrote, “No one can tell a story exactly as it happened. We piece it together. We try to find the essential emotions. In the end, we fall into nostalgia. And if there’s one thing that’s far from truth, it’s nostalgia. So that’s not your story.”

I read The World Is Moving around Me with this premise in mind — that this is a story that’s not his to tell. In the way he follows the stream of events, and renders impressions, images, scenes, and conversations in the midst of tragedy or on its periphery, on the path of nostalgia for places that have been destroyed, for those people who have vanished, for memories wounded and devastated, we feel his restraint, something akin to prudishness. There are no special effects. Nothing literary.

And yet, when a journalist asks him — as a man of letters who has witnessed all of this — what the value of culture is, when faced with such suffering, he answers, “When everything else collapses, culture remains.” In Haiti, nothing is truer. Witnesses will say, and Laferrière will confirm it, that after the initial shock and for the nights that followed, as the tremors continued to punish the city, people joined together to sing as a way of fighting their misfortune. He reminds us of the lesson and the imagery of Haiti’s naïve painters, who choose to portray nature at its most generous, a Garden of Eden, a paradise lost, while all around them, desolation reigns.

The original French-language edition of this book is published in Quebec by Mémoire d’encrier, Rodney Saint-Éloi’s company. Dany and Rodney were sitting at a table at a hotel restaurant in Port-au-Prince when “the earth started shaking like a sheet of paper whipped by the wind.” This book is filled with a sense of fraternity, informed by the love of a country that never deserts its sons and daughters who live far from it. And I’m one of them.

The World Is Moving Around Me

Life Returns

Life seems to have gotten back to normal after decades of trouble. Laughing girls stroll through the streets late into the evening. Painters of naïve canvases chat with women selling mangos and avocados on dusty street corners. Crime seems to have retreated. In lower-class neighborhoods like Bel-Air, criminals aren’t tolerated by a population exasperated by everything it has gone through over the last fifty years: family dictatorships, military coups, repeated hurricanes, devastating floods, and random kidnappings. I’ve come for a literary festival that will bring together writers from around the world to Port-au-Prince. It is an exciting occasion: for the first time, literature seems to have supplanted politics in the public mind. Writers are on television more often than elected officials, which is rare in a country with such a political temperament. Literature is recovering its rightful place. Back in 1929, in his lively book Hiver caraïbe , Paul Morand noted that in Haiti, everything ends with a collection of poems. Later, Malraux, after his last journey to Port-au-Prince in 1975, spoke of a nation of painters. People are still looking for the reason behind the high concentration of artists in such a small space. Here in Haiti, a country that occupies just a third of the island it shares with the Dominican Republic, in the Caribbean Sea.

The Minute

I was in the restaurant at the Hôtel Karibe with my friend Rodney Saint-Éloi, the publisher at Mémoire d’encrier, who had just come in from Montreal. Under the table, two overloaded suitcases filled with his latest titles. I was waiting for my lobster ( langouste , on the menu) and

Saint-Éloi for his fish in sea salt. I was biting into a piece of bread when I heard a terrible explosion. At first I thought it was a machine gun (others will say a train) right behind me. When I saw the cooks dashing out of the kitchen, I thought a boiler had exploded. It lasted less than a minute. We had between eight and ten seconds to make a decision. Leave the place or stay. Very rare were those who got a good start. Even the quickest wasted three or four precious seconds before they understood what was happening. Thomas Spear, the critic, another of the friends I was with, wasted three precious seconds finishing his beer. We don’t all react the same way. And no one knows where death will be waiting. The three of us ended up flat on the ground in the middle of the courtyard, under the trees. The earth started shaking like a sheet of paper whipped by the wind. The low roar of buildings falling to their knees. They didn’t explode; they imploded, trapping people inside their bellies. Suddenly we saw a cloud of dust rising into the afternoon sky. As if a professional dynamiter had received the express order to destroy an entire city without blocking the streets so the cranes could pass.

Silence

When I travel, I always keep two things with me: my passport (in a pouch around my neck) and a black notebook in which I write down everything that crosses my field of vision or my mind. While I was lying on the ground, I thought of those disaster movies and wondered if the earth would gape open and swallow us up. That was my childhood terror. We found refuge on the hotel tennis courts. I expected to hear screams and cries. There was none of that. In Haiti, they say that as long as no one has screamed, death isn’t real. Someone shouted that it was dangerous to stay under the trees. That turned out not to be true. Not a single branch or flower moved during the forty-three seismic disturbances of that first night. I can still hear the silence.

Projectiles

A 7.3 magnitude earthquake is not so bad. You still have a chance. Concrete was the killer. The population had joined in an orgy of concrete over the last fifty years. Little fortresses. The wood and sheet-metal houses, more flexible, stood the test. In narrow hotel rooms, the TV set was the enemy. People sit facing it. It came right down on them. Many got hit in the head.

Читать дальше