When the King finished, a nervous-looking young man in round glasses got up onstage and began to recite a speech. Though he tried to shout over the noise of the now animated crowd, Elvis could only make out snatches.

“ … A country often becomes what its inhabitants dream for it. Much the same way that a novel shapes the writer, the people’s perspective shapes the nation, so the country becomes the thing people want to see. Every time we complain that we don’t want to be ruled by military dictatorship; but every time there is a coup, we come out in the streets to sing and dance and celebrate the replacement of one despot with another one. How long can we continue to pretend we are not responsible for this? How long …”

Elvis lost the thread again as the King materialized beside him.

“Good evening,” Elvis said.

“Sshh, listen. Dis speaker is good.”

“But I can’t hear him …”

“Sshh!”

Elvis strained to hear the young man over the crowd. In the distance somewhere, someone was playing a radio loudly, and he could hear Fela Kuti blowing a saxophone riff. It was an amazing thing to hear, a saxophone player in full flight. He had to really struggle to focus on the young man’s words.

“ … Malcolm X once said America is a prison. So is this country and we are both the jailer and the inmates, imprisoning ourselves by allowing this infernal, illegal and monstrous regime of military buffoons to continue. They continue to play us like fools, buying off our allegiance with money, or with force when they cannot pay the price. I am calling for a rebellion …”

“Let us move away,” the King said. “He is getting carried away, and de army go soon come.”

“I thought you wanted to topple the government! So let them come.”

“Have soldiers ever beaten you?”

“No.”

“Den let’s go.”

“Okay,” Elvis said, following the King out of the square and down to the CMS motor park. “It is good because I need to talk to you anyway.”

There was a cart selling tea, bread and fried eggs. Customers jostled for space to sit and eat on the long wooden benches set around the cart in a quadrangle. Elvis noted the mixed crowd: late-night workers, policemen, security guards on break and the homeless, including a large number of street children.

“You wanted to talk?” the King asked as they sat down on a bench in the far corner of the motor park.

“Yes,” Elvis replied.

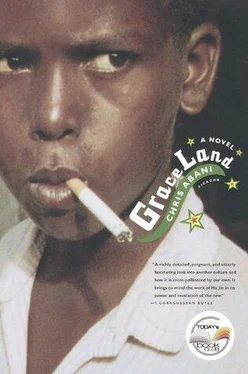

He nervously lit a cigarette and passed the pack to the King, who took one.

“Still smoking too much,” the King said.

“What of you?”

“I am too old for dat to matter. You still get chance.”

“Tea?” Elvis asked, nodding to the cart. The tea had a eucalyptus smell that carried to where they sat.

“Okay,” the King said.

Elvis got up and walked over to the cart. He returned a few minutes later with two mugs and a packet of animal crackers, walking slowly so as not to spill any of the scalding tea over himself. He handed the King a mug, then sat down, blowing heartily on his own. The packet of animal crackers sat unopened between them, like the questions Elvis was almost too afraid to ask.

“So what is it?” the King asked.

“I was talking to Redemption the other day.”

“Uhuh?”

“And he told me that you were his master once.”

The King put his steaming mug down carefully between them. Picking up a twig, he began to pick his teeth with it. Elvis watched warily. There was something disturbing about it. If the King had pulled out a long blade and begun cleaning his nails with it, Elvis couldn’t have been any more afraid than he was then.

“Did he explain?”

“No. He said I should ask you.”

The King laughed loudly, his manner affected and insincere.

“Dat Redemption is a real rascal, eh? I warned you about him,” he said.

“How were you his master?”

“I am de King of de Beggars.”

“But …” Elvis began. Then it clicked. “Oh!”

“Yes. I used to use small boys to beg for me. People like dem more, you see. Me, I look after dem. Dat’s what he means.”

Elvis let out his breath. “I see,” he said.

“Anything else?” the King asked, dropping the twig and picking up his tea.

“Your scar.”

“What?”

“How did you get that scar?”

The King’s hand shook a little and some tea slopped over the tin mug’s side, landing on the table with a loud smack.

“I told you. Soldiers did it.”

“Because of a play.”

The King did not answer.

“Redemption tells me you had the scar even when he was a child.”

“So?”

Elvis was silent. The King let out his breath in a long, drawn-out sigh. Again he set the mug down, though this time he did not reach for the twig.

“You ask questions like police,” he said.

“I am sorry.”

The King nodded.

“So how did you get the scar, really?” Elvis asked.

“Soldiers.”

“Because of a play?”

“No.”

“So you lied.”

“About de play.”

“And the soldiers?”

“Dey did dis to me. I used to live in de north before de war. You were not even born dat time. I work for de Public Works Department, laborer special class. Den de Hausas begin to kill us like chicken. Plenty, plenty dead body scatter everywhere like abandoned slaughterhouse.”

“My father told me about it.”

“Mhmm.” The King nodded. “I manage escape, heading for south, I hide inside train like dis. Just before de train cross Lokoja to safety, soldiers, Nigerian army soldiers, stop de train. Plenty of us dey hide in de train — men, woman, even childrens.

“Anyway, de soldier commander, small boy like dis, maybe lieutenant, drag us all come down. Den he make us sing de Muslim call for prayer. Dose who cannot sing it, like myself, he call us to one side. Den he release de oders, say make dem climb inside de train and wait. De rest of us, my family included, he give shovel say make we dig trench. As we dig, I see de people on de train watching us with pity. I dig well, as a laborer special class. I begin to supervise, telling dem to dig straight and clean, thinking dis will please de officer and he will release us quick, quick.”

The King paused to drink some tea. He was not looking at Elvis, looking away instead into the darkness of Balogun Market, as though the deserted stalls were thriving with a ghost trade only he could see. Elvis followed the King’s gaze, wondering if this was the market where Comfort had her shop.

“When we dig finish, de young officer make us stand to attention in front of de trench for inspection. So we stand, man, woman and childrens, even my wife and childrens too. De soldiers take aim so dat we must stand and not run. Den de young officer begin walking down de line, shooting everybody one by one for head. I fear, I craze, I vex! I take my shovel and try to hit him. One soldier next to me take his bayonet and cut me like dis. I shout and fall inside de pit. Dey leave me so, to die slowly. When he done shoot everybody, de officer take out camera and begin to snap us photo. Den he send de train off and leave with his men.”

“Oh, God,” Elvis said.

“Yes, it is only God dat save me,” the King said. “When everybody leave, I drag myself fifteen mile to de next small town, where dey take pity on me. When I done well finish, I go join Biafran army. Every day, I try find dat young officer, but God save him.”

“I don’t know what to say.”

“Well, I hope you are satisfy as you drag up sleeping dogs for me.”

“I’m sorry.”

“You know how to sorry, but not how not to sorry. Tanks for de tea. Greet Redemption for me,” the King said, getting up and walking away into the darkness.

Читать дальше