This is how the kola nut must be presented.

The actual ritual of the kola nut is as complex as the Japanese tea ritual Not that one needs to compare the two in order to validate the one, but there is something about old cultures and their similarities that bears mentioning.

Afikpo, 1980

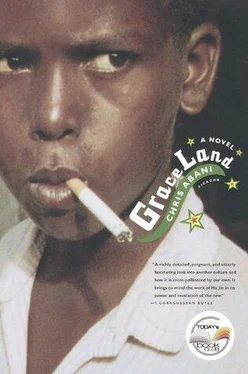

Elvis never took his eyes off the glove. He was standing in the middle of his father’s bedroom. From the window, the stretch of broken asphalt yawned in the midday heat. Houses on either side crowded together as if to revive it. A soft breeze blew a plastic hairdresser’s glove, and it trailed its fingers along the hard surface as though in massage before dancing lightly through the grass at the edge of the road, styling it. The breeze picked it up and slammed it against a wire mesh fence bordering one of the houses. It hung there waving, empty, before slipping lifelessly down into a puddle, sinking from sight.

He had only been inside his father’s bedroom a few times, and then only to clean, which was in itself an invariably bittersweet experience. Tins of smoked kippers, baked beans, corned beef and exotic fruits all sat stacked, unused, unopened. Some, contoured into tortured shapes, were well past their use-by dates. Bought for some special moment that never seemed to come, they were eventually thrown away. Shirts, still shrink-wrapped, mocked the holed one he wore. Vials of holy water, collected from every gifted Catholic bishop or priest between home and Timbuktu, stood in a shaky pyramid in the corner. A sip, taken with a couple of aspirin, worked miracles on headaches, his father swore. In the corners, ornamented tea services leaned against stacks of Reader’s Digests and newspapers.

Everything was thickly coated with dust before he was summoned to clean. He not only had to dust, but also had to move things and sweep under them. The trick was to pack them back precisely where and how he had found them; otherwise he would not get the reward: crumbling, stale, rice-weevil-infested cookies that always left him feeling cheated.

“What did you say?” his father asked.

“Uncle Joseph raped Efua,” Elvis repeated.

“Who told you?”

Elvis was silent. He couldn’t tell his father that he had seen it happen. Not once, but several times. Nor could he tell him that it had started a long time ago. How could he? That would mean having to explain why he had never brought it to his father’s attention before now. It also meant that he had to face up to parts of himself he didn’t want to. This last time, just a few days before, Uncle Joseph had been so rough, slapping Efua around. Even though she was visibly hurt, with one eye closed off, everyone just assumed that it had been a disciplinary beating that got a little out of hand. That happened sometimes, and so no particular attention would be paid to it. Elvis had deliberated whether to tell his father for a long time. And now he did not want to talk about it any longer. Something in his father’s tone and manner brought it home to him. This had been a mistake.

“Who told you?” his father repeated, voice hard.

“She did,” Elvis lied.

“Has she told anyone else?”

“No, sir. Just me.”

His father nodded and reached under his pillow, beckoning Elvis over at the same time. Elvis approached slowly, nearly pissing himself when he saw his father’s old service revolver appear in his hand. The smile was tender as his father placed its barrel against Elvis’s temple.

“If you ever repeat what you have told me now, I will blow your brains out. Do you understand?” he whispered, his face so close to Elvis’s ear, Elvis felt stubble graze his skin. Elvis tried to answer. He even opened his mouth, but nothing came out. His father twisted the gun barrel hard against his temple and said harshly: “Do you understand?”

“Yes,” Elvis croaked, farting simultaneously.

His father smiled, took the gun away and, with his back to him, said:

“Get out, stinking liar!”

Elvis stood still. He heard the words but did not understand.

“Get out!” his father shouted.

Coming to life, Elvis bolted for the door. He fumbled with the lock for too long, and his father was behind him. Elvis’s fear spread wetly down the front of his trousers as a slap connected to the back of his head. There was another silence and Elvis froze, unable to look around. I’m dead for sure now, he thought. Instead, his father leaned over and opened the door.

“Stupid as well,” he muttered as Elvis raced out.

He circled the house all day, far enough from his father to avoid any direct contact or conversation, yet close enough not to be missed. He haunted the edges of the mango and guava orchard his father had planted in a fit of hope when Elvis was still a toddler. “My Elysian Fields,” he had called it.

But here in the orchard, nature had its own designs, and whatever the initial order or plan had been, it soon gave way to a tangled mass of red and white guavas, oranges, mangoes, soursops and bright cherry shrubs. Squirrels outnumbered the fruit, it seemed, and Elvis was reminded of his early childhood when he had hunted the squirrels with the intensity usually reserved for bigger game, armed with his unpredictable catapult that backfired with the sting of rubber or, worse, the lumpy pain of a stone.

Shady and cool, the air was heavy with the scent of rotting fruit and the buzz of tomb flies. The orchard had spread from the west side of the house, where Elvis and Felicia’s room was, all the way around to the front. It had been cut back several times, but the odd guava and mango tree survived in the front yard.

He had brought his mother’s journal with him and he turned the pages, reading with difficulty the curved, spidery handwriting. All these recipes, and yet nobody he knew cooked from recipes. That was something actors did on television and in the movies: white women with stiff clothes and crisp-looking aprons and perfect hair who never sweated as they ran around doing housework for the husbands they called “hon.”

Bored, he closed the book and distracted himself by peering through the window, watching Felicia change. Hidden by the thick foliage, he was invisible. The occasional glimpses of bra, breasts, panties and the anticipation caused his sex to throb. He knew it was wrong to lust after his aunt, but he couldn’t help himself. As soon as it was dark, he slipped out, confident that his father would soon go out and not miss him.

Elvis was headed for the local motor park, where silent westerns and Indian films with badly translated English subtitles were shown after dark. He hardly went to these anymore, preferring to attend matinees in the new Indian cinema, but he was broke. Besides, at thirteen he was far too young to be out alone at night, and his father would kill him for sure if he found out. But the thrill of it was enough to make him disregard the risk, and he felt that it was a secret easy enough to keep. There was no danger of running into relatives there — at least not relatives his father fraternized with. Free movies in the dusty motor park were beneath them.

The films were shown courtesy of an American tobacco company, which passed out packets of free cigarettes to everybody in the audience, irrespective of age. That was half the fun; what could be better than free cigarettes and a free movie? If they could get that here, in a dusty end-of-the-highway fishing town, they thought, America must indeed be the land of the great.

While he waited for the main film to come on, Elvis wandered over to where some of the older boys were playing a game of checkers for money. At fifteen and sixteen, with no parents or interested relatives, these boys eked out a living, either as apprentice mechanics or motor-park thugs. Elvis idolized them and wished he could live their lives. Tonight’s main gamblers were Able-to-do, an apprentice car mechanic and part-time muralist, and Confusion, a sprinter, who made a living playing football for the town’s team.

Читать дальше