To my mum and dad, Carol and David

Contents

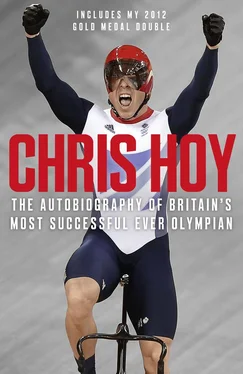

Cover

Title Page

Dedication To my mum and dad, Carol and David

Introduction

1. The Art of Throwing Up in Secret

2. Pimped-up Rides and Broken Hearts

3. Smells of Sandwiches and Mars Bars

4. ‘That Can’t Be Good for You’

5. Going Round in Circles

6. Craig and Jason

7. Holding Your Hand in the Fire

8. ‘They’ll Be Here in a Week to Ten Days’

9. Uncle Mick

10. I Believe the British have Pastries for Breakfast

11. Sydney, Silver and Stig of the Dump

12. Primero?

13. The Chimp Is in Its Cage

14. Some of My Bark Is Missing

15. ‘Would You Like Me to Lap Dance for You?’

16. Taking On the Tour de France

17. The Final Kilo …?

18. A Stroll in Beijing

19. He’s Like Something from The X Factor – the Outtakes

20. Rings and Roundabouts

21. Perfect Ten

22. The Helicopter Technique

23. Pain, and Shane

24. London

Chris Hoy in Numbers

Palmarès

Acknowledgements

Index

Picture Section

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

The Danger of Disappearing up My Own Orifice

On the day after I won my third gold medal at the Beijing Olympics I was visited by a small posse of Scottish journalists, and asked a question I have never been asked before, or since.

‘In the last 24 hours everyone has offered their opinions of Chris Hoy,’ said Gary Ralston of the Daily Record. He may have been stroking his chin as he contemplated how he was going to phrase the next part of his question – I could tell that it wasn’t going to be of the more familiar ‘How does it feel?’ or ‘Has it sunk in yet?’ variety.

‘I wonder,’ continued Gary. ‘What does Chris Hoy think of Chris Hoy?’

There was only one answer to that. ‘Chris Hoy thinks that the day Chris Hoy starts talking about himself in the third person is the day that he disappears up his own arse.’ It maybe wasn’t the response that Gary was looking for, but he, and the others, looked reasonably happy with it, and it duly featured in their stories the following day. (Thankfully, it also got me out of having to offer up a cringe-worthy response to the actual question.)

I bring it up because it popped into my head when thinking about this book. I asked myself: what kind of book would I like to read? Personally, I’m not a huge fan of the straight-forward ‘then-I-did-this-and-then-I-did-that’ life story. What I like, particularly in a book about sport, is an insight into what it’s actually like to compete at a high level, and what it takes to get there, and stay there – ideally sprinkled with a few semi-humorous anecdotes. In essence, I want to know how a sports person does what they do. I want to know why, too, but most of all I want to know how.

It’s the way I’ve always been. At school, I enjoyed subjects where the answers tended to be ‘no’ or ‘yes’. I liked logical subjects – maths, the sciences – which involved some kind of puzzle and a definite or correct conclusion or answer at the end of it. I liked there to be a ‘right’ answer, I suppose, but I also enjoyed the process of working towards it.

I wouldn’t want this book to read like a science manual or maths paper. But I hope that it can go some way to explaining ‘how’. If I were an aspiring athlete, or just a fan of sport – and without referring to myself in the third person – I think that is the kind of book I would enjoy reading.

In any case, I am still just as interested in the question of ‘how?’ as I was when I was a 14-year-old, and making my first, tentative and very nervous pedal strokes around the forbiddingly steep-looking banking of the Meadowbank Velodrome. As I look ahead to the London Olympics, with the knowledge that, just to make the British team, never mind win another gold medal, I will probably have to be a better athlete in 2012 than I was in 2008, the question remains as pertinent as ever.

The irony, of course, is that, while I say I like ‘right’ answers, in reality there seldom is a definitive answer. Training and competing are less an exact science and more an endless puzzle; they are a creative process of trial and error – and a process I enjoy, even though I know that the correct answer one season can be the wrong one the following year.

After 25 years of competing as a cyclist, on BMXs, mountain and road bikes, and finally on the track, I would like to think that I have stumbled on some ‘right’ answers; if I have been paying attention then I should have learnt something. Yet at the same time, if I thought I had all the right answers, I’d be screwed. I know that I wouldn’t get near the team for 2012, never mind challenge for a gold medal, if I thought for a second I could just carry on doing the same things.

So the search, the working out of the puzzle, continues. The answers or solutions to some problems remain elusive, while for others the nature of the problem, or challenge, changes; the variables do what the name implies: they vary. I’m getting older, for one thing – I’ll be 36 by the time the London Games come around – and my rivals are getting younger, if only in relation to me. And so I have to go back to the drawing board, come up with new ideas, and then work even harder.

For me, it’s the puzzle and the inherent unpredictability of sport that keeps it fun – and endlessly fascinating. I hope this book can reflect that and, for aspiring athletes and armchair fans alike, prove interesting.

Chris Hoy, Salford, 2009

1

The Art of Throwing Up in Secret

Beijing, Tuesday 19 August 2008

It was 8.30 when I woke up and hauled myself out of bed. I was lucky, having my own room in the athletes’ village. Jason Kenny, my neighbour in the room next door, had been sharing with Jamie Staff. However, Jamie, whose Olympic Games had started and finished with our gold medal-winning ride in the team sprint the previous Friday, had moved out, so now Jason too had his own space.

It was the final day of the track cycling programme: day five. I had raced on all four days so far, and I could feel it in my legs. First thing in the morning they were stiff and painful, having so far made 14 flat-out efforts in the course of long and draining days at the track.

I could also see the fruits of those efforts, though: two gold medals, from the team sprint and keirin, in the bedside cabinet. I permitted myself the odd sneaky look, though it felt like a bit of a guilty pleasure. I didn’t feel I could – or should – enjoy them until my Games had finished.

That would be today, a day that might even end with a third gold, in the individual sprint. But, bizarrely, there was every chance that my neighbour and team-mate, the aforementioned Jason Kenny, could be the opponent to stand in the way of what, I had been told by journalists a couple of days earlier, would be a historic achievement. No British sportsperson had won three gold medals in a single Olympic Games in a century, I was told. That was news to me: I hadn’t even allowed myself to contemplate the possibility of winning three Olympic titles prior to Beijing, let alone start considering any historical significance. And this morning that was certainly the case: the team sprint and keirin had gone, they were finished. I was focused only on the day’s racing.

The individual sprint starts with a qualifying round – a time trial over 200 metres – and then proceeds over three days with man-against-man contests. Now, two days in, I had made it to the semi-finals. These and the final were both best-of-three rounds, so I would have six more races at most, if I got through my semi and if both rounds went the distance. At 8.30 in the morning, moving my legs slowly and painfully out of bed, then hobbling stiffly towards the shower, I didn’t know how I would cope with that. By bluffing, I imagined.

Читать дальше