I lost the final to Sireau – after another embarrassment, when I managed to fall off the rollers while ‘revving out’ during my pre-race warm up, pedalling at about 250rpm, and clattering very noisily to the floor – but I didn’t mind too much about losing. Like Bourgain, Sireau had had a day off the previous day. He was relatively fresh, whereas I was on my last legs. It was the race against Bourgain that had been important. To have executed it the way Jan wanted me to – that was the breakthrough.

Shane knew it immediately. So did I. I don’t mean that I suddenly thought I could win the sprint title at the world championships, far less the Olympics, but I felt I’d cracked it, to a certain extent. There was this mythology around the sprint – it seemed like a bit of a black art. As a kilo rider, I was seen as a bit of a diesel engine, with plenty of power, but without the gift of great acceleration, and no tactical nous. If I beat someone in a sprint I was often told it was ‘just gas’ – just power – though Shane had always told me I could be a good sprinter, if I just put my mind to it.

Defeating Bourgain was significant because I was beating a tactically ‘better’ rider, and someone who’d qualified faster than me. It wasn’t gas – I was doing what a successful sprinter has to do: imposing myself on the race, and on my opponent. Match sprinting is cycling’s equivalent of a boxing match, with two opponents going head-to-head, or toe-to-toe; it is as much a battle of wills, and confidence, as a test of speed. Finally I had beaten an accomplished sprinter, and it came simply from not letting my opponent do what he wanted to do.

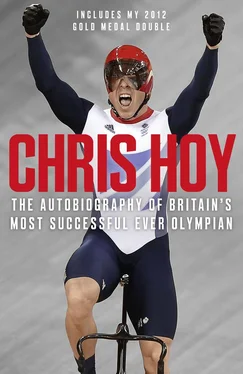

Four weeks later I surprised a lot of people by beating Theo Bos, also by two rides to one, on my way to reaching the final of the sprint at the world championships in Manchester. I then went on to surprise more people – including myself, I think – by beating Sireau in the final to become the first British rider since Reg Harris to be crowned world sprint champion. Harris, whose legendary status is acknowledged in the shape of an impressive bronze statue overlooking the home straight at the Manchester Velodrome, won the last of his five world sprint titles in 1954. Fifty-four years we had waited to claim the title again – and I was as shocked as anyone.

And now here I was in Beijing, with a chance of adding the Olympic sprint title – something no British cyclist, not even the great Harris, had ever achieved. Given all that was at stake it was just as well, really, that as I ate breakfast with Jason, then spent time talking tactics with Jan, I didn’t allow myself to think about the possible ramifications of success. It is one of the golden rules in the British team, drilled into us by our psychiatrist, Steve Peters: focus on the process, not the outcome.

Even now, with only hours left of the Olympic track cycling programme, I didn’t for a second consider the possibility of three gold medals, or the reaction back home to the success we – Team GB in general, the British cycling team in particular – were enjoying in Beijing. Any thoughts I might have had about how life could change in the event of winning that third gold medal would have been about as helpful as a puncture.

At this point, there was only one thing occupying my mind: my semi-final against Bourgain …

2

Pimped-up Rides and Broken Hearts

As a sports-obsessed seven-year-old boy Olympic gold medals were a long way from my thoughts, but bikes were not. Bikes were in my thoughts all the time during my childhood in Edinburgh; they occupied every waking hour, with the evidence plastered all over my school jotters, which were filled with poems about bikes, essays about bikes and detailed drawings of my ‘dream machine’.

It’s probably more accurate, however, to say that cycling occupied every waking hour when I wasn’t thinking about football, and obsessing over my favourite team, Hearts (as in Heart of Midlothian), or later, when I was a teenager, when I wasn’t thinking about rugby, and then rowing.

You get the picture: life revolved around sport. I have no idea how I found the time to do anything else. Such as chess, for example. Chess was my first passion, and in my first day at school, George Watson’s College in Edinburgh, I made a point of asking the head teacher how I might join the school chess club. I had been introduced to the game at the age of four by my uncle Derek, who had what was then an unbelievably modern piece of kit – an electronic chess board. I think I was fascinated both by the game and the novelty of the technology, and played my dad all the time; he let me win initially, before his competitive instincts kicked in. Sadly, my chess playing became a casualty of my all-consuming interest in more physical pursuits. But I’m really not sure I was Grandmaster material.

There’s a story which has been told quite a few times now about how I was inspired to take up BMXing after seeing the bike chase scene in E.T., when it came out in 1984, and I was an impressionable seven-year-old. In fact, it has now appeared in the media so often that I’m sure many people’s instinctive reaction would be to assume that it isn’t true – or am I betraying my relatively newfound cynicism?

It comes as a relief to be able set the record straight at last. It’s true. I was inspired by E.T. to take up BMXing. So thank you Elliott, thank you Steven Spielberg … though I suspect my love affair with cycling would probably have blossomed anyway, sooner or later.

Whether it would have started without BMXs is another question. I really don’t know. All I know is that – thanks originally to what I saw in E.T. – BMXs looked like great fun. What’s more, they were the epitome of cool for a seven-year-old kid.

It wasn’t just the bikes – though they were pretty cool. The padded outfits, complete with motorcycle-style helmets, were cool too, and the tracks were magical places, even the rudimentary ones, of which there were a few in Edinburgh. Not too far from my parents’ home, in Murrayfield, there were cinder tracks at Lochend and Danderhall. Lochend had been virtually destroyed, and Danderhall didn’t have a proper gate, but they were still great fun to tear around on our bikes. The nearest track with a proper start gate was in Livingston, a new town about 15 miles west of Edinburgh, and six or seven of us would travel out there midweek, usually on a Wednesday evening, to do gate practice – the start was critical in a BMX race, and it was my killer weapon.

My mum got me my first bike, for a fiver from a church jumble sale, and my dad went to work upgrading it – pimping my ride, you could say. As a youngster my dad, David, had been quite into bikes himself, or, more accurately, into taking them apart and reassembling them. He built himself a bike out of old parts, which he used for his paper round in Edinburgh (he grew up there too), and when I became interested in bikes he was delighted, because it allowed him to indulge his passion. As I got better and better bikes – having broken the original one doing jumps on a home-made ramp in the garden – my dad’s role as mechanic became even more important. Once a week he’d strip the bike down, clean all the parts, and put it back together, often using the kitchen table as his workbench. My mum, Carol, was remarkably understanding … most of the time.

But at that time the BMX was vying with football for my attention and affection. George Watson’s, a mixed-sex independent school, both primary and secondary, owed much of its reputation to its illustrious rugby-playing former pupils – the Hastings brothers, Gavin and Scott, foremost among them. I played football, which was, if not frowned upon, then not exactly a core part of the curriculum. But we were allowed to play for one year, before being introduced to rugby, and when I was eight I was part of the school team.

Читать дальше