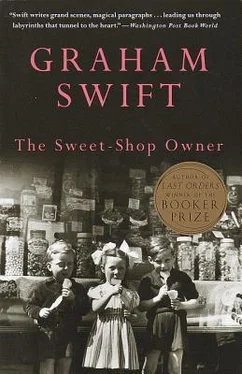

Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Vintage Books USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet-Shop Owner

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet-Shop Owner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet-Shop Owner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet-Shop Owner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet-Shop Owner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I can see his glinting eye as he offered Paul that partnership. ‘I could fix you up here, if you like, old man.’ And I can see Paul’s stiff features trying not to flinch at the condescension — ‘I’ll think about it.’

Where had Paul been all that time? Seventeen years. Seventeen years since he returned from the war, sold up what was left of the Harrisons’ laundry and looked for openings with the money. And it was still a fight, though the war was over, finding the contacts, making one’s mark. Those failed schemes in London; a partnership, at last, in a textile business in Leeds. Irene told me all about it, Dorry. Paul wrote to her. But she never replied, and she never — this was the gist of the story — lent him a penny. And when the business folded in Leeds (and his marriage with it) Paul had no one to turn to but an estate agent friend in London. ‘Great buddies before the war.’ But Irene never went into that. She never did say much about the time before we met.

Soft lights and expensive furniture, in the house where the two friends struck their terms, made their bargain. What did each stand to gain? Paul: a job at the expense of pride? Hancock: the satisfaction of the upper hand? ‘Take your time old man — don’t let me force you.’

But something else was at stake in that plush house. What did Helen hope to gain; a dozen years their younger, getting up from the table, moving perhaps, so they could both watch her, over the noiseless carpet, to look out of the window at the stillness of houses, trees? A little adventure?

Was it true, Dorry, that Hancock beat her, — when it was all over and she came back to him, — so she couldn’t show her face?

How did you know all that? Coming home from school on the bus with John Schofield, who was bookish enough for you not to be troubled by his company. Making fun (that was the fashion amongst free-thinking teenagers) of your affluent parents. But even Schofield, who gossiped so readily with Smithy, wouldn’t have told his own son so much. Paul himself then? Your own uncle. When was it? Those evenings when you said you were rehearsing the school play? Going to Paul’s flat in Camberwell? Did his face still have a trace of those keen looks he wore at my wedding? Did he see Irene in you? Did he welcome you, Dorry? Because he had questions to ask, things to tell; and because you reminded him of a time when the picture was still complete? Under the apple tree, in a black peaked cap. The fair flanked by the strong.

You should have been at rehearsals. You hardly went out otherwise. Mrs Bennet wanted you to play a bigger part. But was it better than drama — all those things he had to tell you?

A little adventure. It didn’t last long. Helen came back and Hancock beat her. The bruises healed but something else didn’t. She had to go for visits to a hospital. She returns there even now on occasion. She still serves the guests at Sydenham Hill; but her giggly laugh has snapped and the faces round the table are fewer now, they say. Hancock doesn’t allow his guests too much laughter. He wears a fixed face like a statue’s — even when he comes in here for cigars — as if he wants to be regarded as beyond reproach. And when I ask, ‘How’s Helen?’ he answers, ‘How’s Dorothy?’

Soft lights over the table. The captured moment.

Why did I wince, Dorry, why did it shock me so, that evening after dinner? You didn’t go straight to your room, and your little head was flushed with anticipation and daring. You made an enemy of Irene that evening. No, it wasn’t what happened with Paul and the Hancocks. She even said of that, with a sort of strange approval: ‘Well — there’s justice there.’ It was that note of adventure in your voice.

You made an enemy of her. But not of me. So why did I wince, as if I were being accused myself, why did I find myself playing the distressed father? — when you placed one hand on the table, drew up your head and blurted out those words as if they were the caption to some vivid and indelible photograph: ‘Something has happened. Mrs Hancock’s left Mr Hancock. She’s gone off with Uncle Paul. I know it’s happened because Uncle Paul told me it would.’

Dorry. You’ll come. You’ll come back.

III

24

The sun blazed in the High Street, but it had lost its morning freshness, and inside the shop, despite the electric fan and the door opened to the street, the air was close and heavy. It made Mrs Cooper itch and prickle beneath her nylon shop coat and grow irritable, so that she glanced more accusingly at Sandra and muttered when the girl got in her way or took her time at the till: ‘Confound you!’ She wiped her glasses. Flies buzzed round the shelves; the counter was sticky; the coins and notes customers handed her were hot and damp with sweat. These things gave her a feeling of distaste — which was quite unlike the feeling she had had as she left home at seven, patting her hair, the dew still bright on the patch of grass by the entrance to the flats, and the word ‘Holiday’ ringing in her mind as something to put before Mr Chapman.

‘Confound you!’

‘Temper!’ said Sandra.

The clock over the door showed ten to one. Sandra went to lunch first, from one to two. Mrs Cooper’s own lunch break was officially one-thirty to two-thirty, but in practice she usually took less. Loyalty to Mr Chapman — and un-willingness to leave him alone for long with Sandra — made her scurry back from her sallies to the supermarket as early as two. Sometimes she took no lunch-break at all, merely sat for a while in the stock room. Mr Chapman never took a break — despite her warnings. Just sat on his stool with a cup of coffee and a sandwich — a cheese sandwich — which he would put down, circular bites out of it, whenever a customer needed serving. Since his wife’s death she herself had begun to cut his sandwich (‘Cottage cheese only Mrs Cooper — doctor’s orders’) or fetch him things from the baker’s. That was a valued privilege. And yet she wished, rather, he’d take a proper lunch. Go over, perhaps, to the Prince William, and leave her solely in charge. Hadn’t he said, on that wet evening sixteen years ago, that there’d be times when she’d have to mind the shop herself? And yet it seemed that, except for those visits to the hospital, which were over now, he’d never yet trusted her to be alone regularly at the counter.

Fridays had their consolations, it was true. She and Sandra took their lunch as usual, but at two-thirty Mr Chapman would leave, taking in his briefcase some packages from the safe in the stock room, and drive over to Pond Street. There were the two to be paid over there — Bryant and Miss Fox — and the odd order to discuss. He would be gone perhaps three quarters of an hour, and she would relish that time as an opportunity to hold sway over Sandra.

She took her eyes from the clock. Five to one. Sandra fidgeted by the till. Oh yes, she ’d be ready to dash off on the stroke. Flitting down the High Street, ready to fritter away her pay-packet. She thought of setting the girl some task that would cut into her lunch time.

‘Sandra,’ she said commandingly, ‘before you go to lunch —’

But then Mr Chapman surprised her.

‘That’s all right, Mrs Cooper. I’d like you to go to lunch first today.’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘If that’s all right.’ Mr Chapman edged forward from the refrigerator. ‘Sandra was late. I think you should go first, for a change. Let her cope with the lunch-time rush.’

She stiffened.

Change? She always went to lunch second; the pattern had never changed.

‘But I always —’ she began. But Mr Chapman’s glassy look made her falter.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet-Shop Owner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.