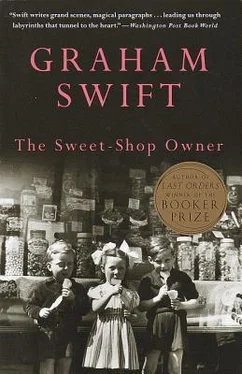

Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Vintage Books USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet-Shop Owner

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet-Shop Owner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet-Shop Owner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet-Shop Owner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet-Shop Owner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Blue jeans and a purple corduroy jacket; hair long and straight and unstyled. Alone in that room the other side of London, with a gas-ring, your books and your independence. Don’t think I wasn’t proud of you, Dorry. My own daughter at university. But why didn’t you seem glad, even at your own success? And why did it seem to me (other youngsters, whom I winked at, over the counter, wore those bright, flamboyant clothes because it was fun) that you wore your student’s outfit as if it were only another uniform?

Who was happier, Dorry. you or I, when we were twenty?

You even came back to us that summer — tired of that gloomy bed-sitter where no one had forced you to go. You caught the train up to your lectures in the morning, and did not return, often, till late, very late. Irene would look at you when you were late as if testing you for something.

But they found you a new room, the next autumn, in one of the halls of residence. Small and neat. There was an anglepoise lamp; a pin-up board; a bed which folded back against the wall; and scarcely enough room on the formica shelves for all your books. But you would be looked after there. There was central heating and a launderette and they would clean your room for you and give you meals in the dining hall; and it was for you they’d built those new clean-lined buildings (there were still piles of scaffolding and sand beneath your window), employing the best architects to draw the plans. See how far the milk and orange juice had gone.

And you wouldn’t be lonely, for in that neat residence hall, like a luxurious barracks, there were fifty other girls like you, each with a room like yours with a number on the door and a slot for a name-card. I saw them, and felt embarrassed, as I helped you carry in your cases and bags. They giggled or gave little aloof, intense glances. Doors were half opened and record-players competed. As we passed along the corridor I glimpsed them, sitting on beds and floors, looking serious, cradling thick coffee mugs, demonstratively smoking cigarettes.

New, clean-lined buildings; purple bricks, glass, and wooden slats; newly-sown grass outside your room in which rows of saplings had been planted. I felt old and out of place as I left and walked round the grass to the car; so that I was relieved by the gardener, with raw-looking hands, tying up the saplings, who nodded as I passed.

You stayed there two years — oh they moved you in your third year to another building, a bigger room, but it still had a number and a name-card. You came home in the holidays and sometimes you phoned and sometimes wrote. But it seemed as if you could never tell us clearly what you were doing or what was happening. ‘I’m working hard,’ you said. ‘My tutor says I could get a First.’ As if all that time you spent, until the beginning of that last year, were spent in waiting, waiting.

‘Ingratitude,’ we said, like an excuse.

‘Don’t you miss her, Mr Chapman?’ Mrs Cooper asked, stirring the morning tea.

‘She’s only the other side of London.’

‘And she’s grown up now of course, isn’t she? Old enough to lead her own life.’

Her eyes had swivelled behind the spectacles, looking for reactions.

‘What is it she’s studying exactly? English? I mean, what’s it for?’

‘Oh — not like this’ — he glanced at the newspapers. ‘Literature. Poetry.’

‘Oh.’

The gaudy colours of the toy display in the Briar Street window were reflected in the lenses of her glasses. Her sleeve brushed the magazine counter from which young faces grinned and pouted: Honey, Nineteen, Disc, Melody Maker. She looked grave, unmoved, amidst all the dazzle.

And yet, he knew — in eleven years he’d had time to discover it — that beneath her toil and tenacity, Mrs Cooper nursed dreams of her own.

1969. The kids were coming out of school, barging down the pavement as if the world was theirs. And stepping out, at the kerbside, from a pearl-grey Rover and having to pick his way through them, was Hancock. He walked briskly and purposefully — as well he might. For those house prices were rising, faster and faster. There would be a real boom soon: thousands added in a matter of months. He would flatter himself he’d foreseen it and watch the fees flow in (as he himself, behind his counter, watched the money fill the till — four hundred, five hundred pounds a week).

But there was a stiffness now and an aloofness in Hancock’s bearing as he stepped, scarcely seeing them, through those waves of school-children. No swagger in those long legs; no roguishness in that once sprightly face. As if all that had stopped, years ago.

Was it the stiffness of discretion — or of age?

26

Clomp, clomp. What was that? Smithy’s young assistant Keith, hastening into the shop in his new leather boots and flared trousers, and standing for a moment, open-mouthed, in the middle of the floor, not seeing him as he crouched, replacing stock behind the counter — while the little spasm in Mrs Cooper’s throat — he saw it even from where he stooped — rose in sudden alarm.

‘Mr Chapman!’

For all his twenty-one years, the smart clothes, the medallion round his neck, Keith looked for a moment like a helpless schoolboy come to seek the master’s aid.

‘It’s Mr Smithy, Mr Chapman. I don’t think he’s breathing.’

Wail of the ambulance up the High Street and the flash of its blue light as it passed the Prince William and Powell’s and the Diana and drew up beyond the entrance to Briar Street. It parked close to Smithy’s door. The ambulance men made an attempt at concealment, opening the rear doors ready. But people had stopped to watch — Mrs Cooper watched through the window full of toys — and they had time to see that the body on the stretcher as it was carried out was entirely draped by the red blanket.

‘Through here, Mr Chapman. Look.’

And there, in the little back room of the barber shop, was Smithy, in the easy chair, his head to one side, the glass of water that he was going to drink smashed on the floor. ‘Don’t touch anything,’ he said. ‘Nothing must be touched.’ Although why he said it, he didn’t know. Nor why Keith and Sullivan, Smithy’s other assistant, bowed, ditheringly, to his command, put the ‘Closed’ sign on the door when he told them, sent away the single customer stiil lingering, half-shorn, in the shop, let him deal himself with the ambulance men.

November the sixteenth, 1969. The figures on the pavement who had stopped to look moved on and the traffic in the High Street seemed to resume a halted progress like a film jerking back into life. In the shops they returned to business, to sudden energetic talk, activity. But they had seen: old Powell behind his racks of fruit, Hancock behind his photographs of property, and the proprietor of the Diana pushing aside the plastic menu placard hanging in the window. And they’d known. It was Smithy.

‘Did it go all right?’ she asked as he appeared at the door in his coat and his black tie. He shrugged.

She returned to her seat, under the standard lamp, and seemed just a little perplexed when he did not sit down immediately after entering from the hall, but stood looking out of the window at the lilac tree.

‘Grace all right?’

‘She’s not taking it badly. She’s going to her cousin’s.’

That afternoon at the crematorium he’d stood with the little group of mourners and helped Smithy’s sister in and out of the car and apologized because Irene was too ill to come. And Grace had said, ‘Look after that wife of yours’; and he’d said with a wan smile, ‘Oh, it’s she who looks after me.’

She watched him sit down and not volunteer further comment.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet-Shop Owner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.