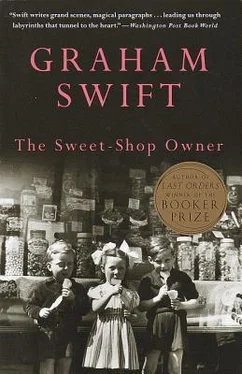

Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Vintage Books USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet-Shop Owner

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet-Shop Owner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet-Shop Owner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet-Shop Owner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet-Shop Owner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In the car you asked: ‘Well, what did you think?’ ‘Oh I thought you were good.’ ‘No — the play,’ you said. And I muttered something feebly in reply. What did I know about Shakespeare, Dorry? I’d sat in an uncomfortable wooden chair after a hard day at the shop, while on the stage schoolchildren in costume played the parts of grown-ups and spoke lines I did not understand.

You were almost sixteen. Little hillocks of breasts had grown under your school pullover, and you were aware beneath your skirt of the contours of your legs. You crossed them carefully and tucked your skirt under your knees. You tried to pretend that you weren’t attractive — though, in the play, a schoolboy lover had wooed you with long speeches. But you couldn’t do it by covering your knees, or letting your hair fall over your face, or raising arguments with us over the dinner table so as to divert attention. And besides you knew — lingering by the mirror and looking sideways at yourself as if you didn’t want to see — that it couldn’t be hidden. And you really wanted, didn’t you, though the thought of it frightened you, to live up to it?

Down the High Street after school. It wasn’t the quickest way home. Was it to receive the darting glances of men leaning from car windows as you crossed at the zebra, looking up, turning their heads as you passed on the pavement, muttering low words? Or of boys your own age sauntering circuitously home, in restless gangs? I saw them meeting girls in Briar Street, next to the cinema adverts. Mrs Cooper tut-tutted and sometimes banged the window to shoo them off. Their breath steamed in the dusk. They wore Parka anoraks. Their hair was longer than the school approved, their trousers tighter; they carried records, with their school books, under their arms — the Rolling Stones and Donovan with text books of physics and geography. And it wasn’t Shakespeare and poetry they spoke of. Was it that, Dorry? Did you have to run that gauntlet, to test yourself? Though it made your head sit uneasily on your shoulders and you didn’t know how to reply with any naturalness to those adventurous looks.

Nothing touches you, you touch nothing. Sixteen, in a blue school beret. You could have kept your poise and learnt the trick of it. You were beautiful and young. Wasn’t that something to rejoice over? You could have performed the trick, without fear and without needing to make your mark. For hadn’t you once — at the schools swimming gala — stood up, unafraid, high over the swimming pool, over the blue tiles wobbling beneath — that was no adventure, you knew how to keep your balance — and hadn’t you plunged, with a perfect arch, and bobbed up again, to take second prize, with a laugh?

Shakespeare, history books, volumes of poetry. Post-cards from art galleries — replacing Kennedy — on the wall; and faded ink-splotched school copies of Latin texts, Virgil and the Metamorphoses , whose contents I puzzled from the English heading before each extract: ‘Narcissus and Echo’, ‘Diana and Actaeon’. I put the mug of coffee on your desk, knocking first at your door, and treading softly over the carpet. For your head was lowered and you were intent on your reading. Your hair hung forward in the light of the anglepoise lamp and the line of your neck seemed fragile and exposed as you leant. You were doing your project on Keats and over your shoulder I read lines of verse (did you know, Dorry, how I peeped into those books when you weren’t there?) which I didn’t understand:

Bold lover, never, never canst thou kiss …

I put the mug on your desk. You said in a quiet, unsteady voice, ‘Oh thanks,’ but you didn’t turn and smile at your father.

23

We bought you dresses. She would have said: She doesn’t need them, not so many — but she yielded, for my sake. Bright dresses — how they changed, Dorry, as you grew up, from wide skirts to little skimpy things next to nothing — lying over the back of a chair for you to find at Christmas or on birthdays. Dresses to make a young girl feel special, and that cost her father a pretty penny. For we had money. Thirty, forty pounds a day. I worked all day Sundays, and we no longer took holidays. And even without the shop we had money. For she still scanned the closing prices in the paper, made phone calls, and struggled out, in her weak state, to meet agents, and sign cheques for crystal and porcelain. ‘They’re beautiful,’ I said of all those things she bought. But she replied, her tired eyes somehow disinterested: ‘They will keep their value.’

Bright dresses — deep red suited you best — that should have been worn at dances and parties. Weren’t there parties to go to? I sometimes saw them, driving home late from the shop, in Mannering Road and Clifford Rise and in Leigh Drive itself: little gaggles, sixteen and seventeen, no older than you, in short skirts and leather jackets, arriving at bay-windowed houses where the parents were out for the evening or away for the weekend, and from which record-players boomed. ‘ Talkin’ ’bout my ge-en-eration … ’

But you didn’t wear those dresses. You put them on to please me — you came down the stairs and stood like a shy doll in the doorway. And you wore them on the predictable occasions (do you remember, Dorry, those drear Christmases, when we dutifully had the neighbours in for drinks and you and I walked after dinner, not talking, round dark, empty streets, where the decorations in front windows looked like shop-fronts?). But you didn’t go out in them, though you liked them and thought you deserved them — I saw that. You hung them up in your wardrobe and preferred your white school blouses and navy skirts or that shapeless brown sweater and slacks.

No parties. No self-conscious but light-headed youths ringing at the front door to take you to dances and cinemas. Were you above that? Was it more daring excitements you wanted? Or had she spoken to you — surely not — told you of wolves that prowl? No time to go out. Books to be read, exams to be worked for, essays to be written.

Yet you knew, nonetheless, John Schofield — Schofield’s lanky and precocious son who’d done the lighting at the school play — and you knew more than I did about what was going on up there, amongst the trees and the old villas and the new estates at Sydenham Hill. You told me it all later — that time, the first time, she was taken to hospital. That was the only time we ever really talked.

Houses through the trees, and lights, illuminating costly furniture, in the houses. That was where your mother’s family had a house; and I remember when it was mostly all woods and fields and my father used to walk there on Sundays. They’d built a lot up there: luxury houses for executives, tall, clean-cut flats, but with banks of turf and carefully preserved clumps of trees in the best of taste. The people inside the houses were building too. Hancock was building (you never liked him because of his businessman’s swagger — too crude a contrast to me? — but most of all because he winked at you once as you came home from school): new branches in the suburbs; bigger figures on the ‘For Sale’ signs in his window. And Helen was building. More gadgetry in the kitchen so she could lounge and entertain more. A bigger wardrobe so she could lounge more prettily; richer fare on the side-board so she could entertain more lavishly. You wouldn’t remember her from your christening; her breathy charms and her quick shrill giggle. Hancock had chosen her for her obvious looks and curving figure. For he wanted a wife to prove his merit, a prize on display other men might envy.

Candlelight on the faces of the guests at table and on the bare arms of the hostess serving the meal; jokes about the cost of living, and an atmosphere like that before a race where each contestant smiles sportingly and wills the other to lose. It wasn’t enough, that enviable trophy. More business, more houses to sell. More adornments for wife and home so that the prize would prove the achievement. And though he strode over the High Street with that swaggering gait his restless face was never content.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet-Shop Owner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.