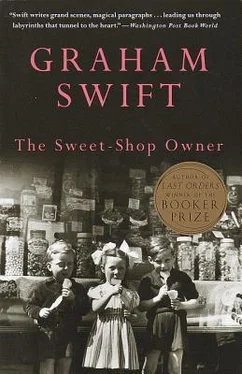

Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Vintage Books USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet-Shop Owner

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet-Shop Owner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet-Shop Owner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet-Shop Owner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet-Shop Owner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Only a story,’ he said, twanging his braces like catapults — and was that a smile at the corners of her lips?

He took the toast from the grill and the boiled egg from the bubbling pan. She did not eat breakfast, only drank the tea, but the table was laid, the blue and white crockery, the pale blue napkins — even at six in the morning. Darkness pressed against the window-pane, where in summer they could see the dewy lawn, the lilac tree, its stem grown thick after twenty-five years. The house was still, save for the tap-tap of his spoon against the egg and the ‘heee … heee’ of her breath, and you would scarcely have known that in the room above Dorothy lay asleep, books on the shelf over the bed where once they had propped the striped woollen doll and the jig-saws. Every morning as he went down to make the tea he paused to listen at her door — why did he listen? — and sometimes he heard her stir, wakened by his own movements. But stillness usually. Stillness: so that sometimes, far from complaining, he pitied the seven and eight o’clock risers who did not know the early morning calm, before the traffic began, before the world jerked into action. Her breath hissed in the chair opposite his. There were wrinkles in the cleft of her breasts. But she drank her tea deliberately, holding the cup between her hands, dipping her head forward rhythmically to sip; and as she drank she seemed to be saying too: ‘Yes, this is the best hour. You will go, to your old place, and return. Dorothy is still in bed. And I can sleep now. The day is poised; for an hour or so there is peace.’

He checked his pocket for the keys, his wallet, picked up his briefcase. She helped him on with his oatmeal scarf. It might have been he who commanded, as he drew the dressing-gown about that wheezing throat and said, ‘Stay in the warm’; were it not for her answering eyes: ‘Go on, go on.’ Past the hall mirror, the umbrella-stand and out into the dark morning — a frosty ring as his feet struck the front path — where sometimes it seemed he was quite alone in a world which had suspended its activity. Under the amber sodium lamps. And even in the shop, after he had sent off the paper boys (they were a different bunch then but their careless loyalty was the same) there was still a calm. Those minutes before he opened. A few cars in the High Street, footsteps, scuttling on the pavement. Soon they would be coming in their droves, summoned by trains, clocks, streaming to their work, bustling in at the shop door for their daily purchases. And he would be there, bobbing at the counter to receive them. ‘Morning Mr Casey, morning Mr Saville, Mr King.’ All was ready. But he would listen, for a few minutes, to the crinkling of the shelves, the hum and tick of the fridge, and sniff — it was still there but no one but he perhaps could smell it — that faint whiff of coconut he had first sniffed when the shelves were bare and dust lay on the counter and old Jones had stood in his black coat. Stillness. And while he waited, hands resting on the morning’s headlines, he laughed inwardly, not the old laugh — a dry laugh, thin like her breath, which didn’t change the look on his face. But a laugh.

And that same year, when he was fifty and the shop twenty-five years old, he said to her one night, closing the maroon books — her smile had lit her face then — ‘Toys, I will sell toys.’

21

Dorothy. Why did you have to come into the shop? To disturb those patterns? To see my look of disguised excitement, faint apology, as I greeted you from behind the counter? To hear the catch in my voice as I said, ‘Mrs Cooper, my daughter Dorothy’? You could have got the bus as far as the Common Road, but you got off in the High Street, in your blue uniform and your blue beret, a satchel under your arm, and walked down to the corner of Briar Street. To see me without Irene? To see if I was any different without her?

Half-past four, five o’clock. Under the brightening lights, through the deepening dusk, other children were going home from school, in groups, in reckless gaggles, but you always seemed alone. Even when you came in flanked by your friends — Sally Lyle and Susan Dean — you stood apart, untouched by their boisterousness and their forwardness, watching them giggle at the counter and say, ‘Oh, Mr Chapman!’ as I slipped them free chocolates. Though anyone could see, of those three, you were the prettiest, the one who most deserved to be to the fore.

You watched me arrange the toys in the Briar Street window. For they were arriving now, picked from the wholesalers’ catalogues, in boxes that rattled and squeaked and threatened to jerk into imitation life. Meccano and Lego, Yogi Bear dolls and model kits of the Lone Ranger. There was a frown on your face as I clambered into the window with them. A man of fifty fussing over toys? But it was my job to sell them. You stood with your arms holding that satchel in front of you and your fingers tapping restlessly on the leather, for you never quite knew what to do with those long, delicate hands. You’d let them fall awkwardly by your side and sometimes one of them would reach up, just like her, to your throat, but you’d remember suddenly and let it drop quickly again. ‘Here,’ I said, ‘put that satchel down, you can help.’ And you were in two minds whether you ought to or not. I got out from the box the set of three little clockwork chimpanzees. Each wore a hat like a fez. One had a pipe, another a tambourine, another a pair of bongos, and when you turned the key in their backs their heads swivelled and their arms moved. ‘Where should they go?’ I said. And you said, hesitating at first, and then with a little sharp decision, ‘Why not there?’ — and pointed to the display rack over the counter above my head. I hung them there, Dorry (you see, I didn’t question, didn’t hesitate). And later, when I’d sold three sets of those monkeys and people pointed to the ones above me, I said, ‘No, they’re not for sale.’ ‘There,’ I said, fixing them, ‘like that?’ But you looked away.

For you’d finished with your own toys. You thought we’d thrown them out, but I merely put them, to be kept, in the trunk in the spare bedroom. You no longer wanted to play or be thought of as a child. You’d got a place at the High School; you were going to make your mark, and it wasn’t games you looked for any more. Was that why you walked uneasily between your breezier friends? Why you buried your face behind books? And why you threw those little fits and sulks at home, picking quarrels over the dinner table — for that was a way of creating a little drama, of making your mark, without ever having to leave familiar ground?

‘Doesn’t it bother you?’

You raised your head and spoke urgently, so that we stopped and looked at you, our spoons half-way between plate and lips.

‘Doesn’t it bother you — that there might be a war?’

On the leather foot-rest by her chair were the papers she’d been reading. Their headlines said: ‘Ships Move Towards Cuba’, ‘Britain Urges Removal of Missiles’.

You looked at her first and then, when her lips tightened in annoyance, to me, to see if I would move to her defence or yours.

‘There won’t be a war, nothing will happen,’ she said.

‘How do you know?’

‘I don’t. It’s what I think.’

She resumed eating. You watched, not eating, your face trembling. I thought: thirteen, and talking of war. And then you flung down your spoon and pushed aside your plate.

‘Neither of you care! What do you read the papers for if you don’t care what happens? It’s not something you can just ignore —’

‘No — nor is it something to make a scene over when we’re eating. If you want an argument, have it with one of your fancy teachers at school, don’t be clever with us at the dinner table!’ She began suddenly to gasp for air.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet-Shop Owner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.