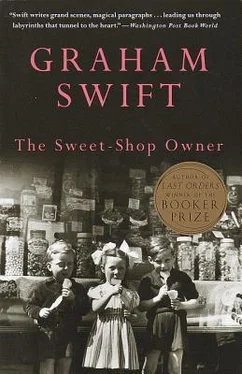

Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Graham Swift - The Sweet-Shop Owner» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Vintage Books USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweet-Shop Owner

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweet-Shop Owner: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweet-Shop Owner»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweet-Shop Owner — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweet-Shop Owner», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Shall I tell you something?’ she said. ‘I once went into Smithy’s shop. It was in the war when I was in London with Father. I went to see the shop was all right; and then Smithy gave me a cup of tea, in his back room.’

‘You went into our shop?’ he said.

‘Yes.’ Her face was hollow and thin, but the gaze was firm, as if she’d known at the time she would store up those past moments to recall them now.

‘That was nearly thirty years ago,’ he said.

It wouldn’t last. Outside the hospital the flower-lady trimmed and cut her bunches of flowers. Doctor Marsh replaced Doctor Cunningham on her appointment card, but Doctor Marsh could do no more than Doctor Cunningham, save to send her to Doctor Fletcher at St Thomas’s. But that was not for the asthma; that was for her heart.

‘Brrring! Brrring!’ The telephone rang on the shelf next to the cigarette racks and Mrs Cooper answered. Over a year since Smithy’s death; and Sullivan had taken over the barber shop and the red and white pole no longer twisted over the corner of Briar Street — ‘The wrong image for today,’ Sullivan said.

‘It’s Mrs Pritchard.’

Mrs Cooper held out the receiver, and as he took it, placed it to his ear, and watched the expression of peculiar anticipation on Mrs Cooper’s face, it seemed to him he had already heard the terse message, had already thrown his coat on and was driving, dry-mouthed, to the hospital; had enacted that scene, many times, before, though he never believed it was real — so that the thin, frightened voice of Mrs Pritchard (the woman they’d hired to do the housework) sounded like some voice from inside him:

‘It’s Mrs Chapman. They’ve taken her to the hospital.’

27

How strangely untroubled you looked, appearing there at the swing door which the nurse, raising a finger and pointing, opened for you. You had come at once, taking a taxi at each end, so that it seemed you arrived only minutes after I phoned. You wore a long, dark-red dress under your coat, and black boots, and you walked with a sure and steady stride, so that I thought: Yes, she too seemed to look her best in times of trouble — against the dark-green blackout curtain; walking down a corridor in that same hospital, where her father died.

We hugged. Your cheek was cold from the wintry air outside but your breath was warm. We had never embraced like that before. You squeezed my wrist, and went to speak, purposefully, to the sister, and you didn’t seem the same girl as I’d left in that neat room with its number and its slot for a name-card.

‘Listen Dad, it wasn’t a severe attack. She’ll be all right. The same as they told you. She’s been sedated. There’s nothing we can do here. Let’s go home.’

How untroubled you looked. You sat me by the fire, made tea and cooked a supper which I didn’t want, but which you made me eat. I ate slowly, in silence. And then we talked. That was the only time we ever really talked. I told you about old Harrison. Why did I dwell on old Harrison? He lay in a coma in that same hospital in 1945, while outside they danced and sang and celebrated victory with bonfires. And you told me — that was the time you chose to tell — about Hancock and those meetings with Paul. I never knew you knew so much about her family. And you spoke with a commiserative and tentative look, as if you were telling me something that ought to be kept from me.

For there was one thing you didn’t tell me that night, wasn’t there? Though I knew. Don’t ask me how. Call it a father’s instinct. You sat in the armchair opposite, leaning forward, your face like a torch in my eyes, and now and then your hand pulled smooth that red dress over your knees. But that movement wasn’t like it used to be. There was something new in your voice and in your eye, and I knew: it had happened at last; you were no longer waiting, waiting. When, Dorry? It must have been sometime that term. Where? In that neat room with its number on the door and its rows of books?

‘So Grandfather gave her the money?’

‘Yes.’

‘But why her, why not Uncle Paul or Grandmother?’

‘Because he wanted, I think, to be forgiven.’

‘For what?’

‘I don’t know. He always made demands of her. They never got on.’

‘And that money bought the shop?’

‘No — this was after the war. We bought the shop in ’37. She had some money when we married.’

‘And Grandfather’s money?’

‘Hers. None of it went into the shop. I think she felt it wasn’t to be touched. She made sure it kept its value. Her investments — and all these things.’

You looked around pensively at the crystal and the china behind the glass in the cabinet. You seemed glad to be alone with me.

‘But after Grandfather’s death you needn’t have kept on the shop.’

‘No — but we did.’

‘And then she never saw her family again, did she, after the war? I mean, Uncle Paul and Grandmother —?’

So many questions, Dorry, about the past — when you had stepped so boldly into the present. I paused, peered into my cup of tea.

‘But how are you doing now? Things okay?’

You lowered your eyes. You didn’t want to answer questions either.

‘Oh — I’ve started the special paper for Part Two.’

‘What’s that then?’

‘The English Romantic Poets.’

The mantelpiece clock chimed one in the morning. Late enough. But I didn’t want to go up to lie alone without her, and to think of her lying alone. Or to leave you.

I said, ‘I’ll phone the hospital.’

‘No — it’s all right. They’ve got our number. If there’s any need they’ll phone you.’ You pressed me back into the armchair.

‘Don’t worry, Dad, she’ll be all right.’

‘All right now maybe.’

You sighed reproachfully, at those despairing words.

I said, ‘You will forgive her, won’t you? You won’t be hard on her?’ You glanced up again questioningly. ‘I know it seems she’s always been against you.’

‘Oh — that was only really since that business with Uncle Paul …’

‘No, but before, before. She always … she always found it hard to be — to give certain things.’

‘Things?’

‘You know what I mean. You know.’

You frowned.

But I saw you knew.

‘What I want to say is that she was always like that. It was the same for me too.’

‘Even when you got married?’

‘Yes, I suppose even then.’

‘So you knew what you were doing?’ You looked at me like a woman who means to get her way.

‘No, Dorry. No, I never did.’

I put my head in my hand and looked up through my fingers at your eyes.

‘Forgive me too.’

28

Sandra rocked gently on her stool. The lunch-time rush of customers had slackened and the clock was nearing two. She wasn’t bothered by Mr Chapman’s switching of the lunch-breaks — she had none of Mrs Cooper’s mania for routine. After Mrs Cooper had left she’d sighed, puffing out her cheeks and said, ‘She’s a fusser, ain’t she?’ — but he hadn’t taken up the point. And now he was looking at her again from his stool by the fridge — oh not in a way she was used to (the way old men looked at her on buses and trains), but almost disappointedly, regretfully, as if he expected her to be something she wasn’t.

‘And what will you be doing this weekend, Sandra?’ he suddenly said.

‘Oh — might go down the coast, Sunday. Or up the swimming pool.’

Her shoe slipped from her foot beneath the counter onto the floor, but she made no effort to retrieve it. She ran her toe over the wooden panel on the inside of the counter. Her legs were sticky where they crossed. Her cheek rested on her palm which was sticky too. Still he looked. She kept her eyes to the front of the shop where, beyond the window, the sunlight flashed on car windows and, to the right, on the empty beer glasses on the low wall outside the Prince William. ‘Well, sorry,’ she said to herself, recrossing her legs and wondering simultaneously what she would do at the weekend, ‘Whatever it is, I’m not it.’ And she turned at last to Mr Chapman, whose heavy, purplish face seemed suddenly quite forlorn, like some stone figure that has inexplicably melted and lost its shape.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweet-Shop Owner» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweet-Shop Owner» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.