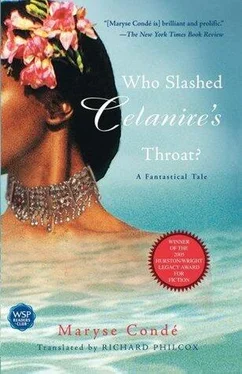

Maryse Conde

Who Slashed Celanire's Throat?: A Fantastical Tale

For Raky, who will not take the trouble to read me

1

This was not the first time the Reverend Father Huchard, a long-standing member of the African Missionary Society in Lyons, had landed on these shores. He was an old-timer and had already spread the word of God among the natives of Dahomey as well as those in the Lower Congo. So it was of no surprise to him that the land was so flat, the forest beyond so impenetrable, that the rain over his head never let up and the sun up there, way up there, was so hazy. His eye was fixed on one of his flock of six: an oblate who answered to the name of Celanire. Celanire Pinceau. A most unusual name! The priest’s gaze, however, did not betray any covetous look. It was simply the fact she stood out from the others. She hardly spoke. She did not seem curious or excited like her traveling companions, who were eager to begin their missionary work. What’s more, her color set her apart, that dark skin that clothed her like a garment of deep mourning. Her features were not strictly black — rather, a hybrid of goodness knows how many races. She did not wear religious garb, since she had not yet taken her vows, but wore a somber gray dress and a scarf around her neck tied with a ribbon from which hung a heavy gold cross. Winter come summer, morning, noon, and night, this tightly knotted scarf never left her and matched the color of her clothes. Where did she come from? From Guadeloupe or Martinique. Well, from one of those colonies that are only French by name, where the natives have been baptized yet still run wild, swear like heathens, beat the drum, and drink strong liquor. She was an orphan raised by the Sisters of Charity in Paris whose desire to do missionary work in Africa had made her join the nuns of Our Lady of the Apostles in Lyons the previous year. Reverend Father Huchard, who had kept his eye on her throughout the voyage, was no wiser now than he had been when the Jean-Bart first sailed out of the Gironde estuary in a great swirl of muddy water. The fact was that whenever he regaled his audience with stories about the natives, and he had seen some in his time, she had a way of staring at him that made him ill at ease and reduced him to silence. But there was nothing serious to report. She wasn’t insolent. She wasn’t disobedient. Even so, Reverend Father Huchard didn’t trust her and believed she was capable of anything.

The flotilla of small boats bobbed toward the old freighter, braving the wall of waves, jostled each other on reaching its side, and the passengers began to descend, the women standing in large metal baskets, clasping their skirts around their legs, the men gingerly clinging to the rope ladders. As they gradually boarded the boats, the smell of unwashed body parts wafted up.

It was the long rainy season, the one that stretches from April to July. The sun’s beacon cast a reluctant glare over the immensity of the ocean’s swell. The land remained at a safe distance behind the line of rollers, a land devoid of life and houses dotted among the greenery. It was a grayish, spongy land, in places eaten away by the mangrove swamps, in others wrapped in a shroud of vegetation. The sky was low, smeared by streaks of clouds. The silhouettes of the African porters could be seen fending off the torrential rain as best they could on the wharf while the European officials huddled under black umbrellas as voluminous as church bells.

At the time when this story begins (but is it the beginning? Where in fact does it begin? That’s anyone’s guess!) they had barely finished burying the dead at Grand-Bassam. An epidemic of yellow fever had laid to rest all that remained of the Europeans in the vicinity, resulting in the decision by the governor, Roberdeau d’Entremont, to transfer the capital to a more salubrious spot, a few miles distant, on the plateau of Adjame-Santey. In response to the barrage of objections regarding the cost of the upheaval, he pointed out that the many springs located beneath the plateau would provide an ample supply of water, which was not the case with the present capital.

Despite its misfortunes, Grand-Bassam proved to be a pleasant surprise. Forty years earlier it had been a stew of fresh and salt water trickling into the bush, emitting deadly miasmas. Now a neat little town had emerged from the sand, white as snow. There were not only the houses in the French district. A grove of coconut palms added a touch of green beside the Governor’s Palace and the offices of the Western Telegraph Company. The Governor’s Palace, built entirely of prefabricated material shipped from Bordeaux, was a rich example of French technology. Along the banks of the river Comoé stretched the Essante district, or District of the Converted. It was thought the souls of the newly baptized could be saved by herding them into huts made of palm fronds and branches. Life was returning to normal following the latest epidemic. The warehouses piled high with casks of palm oil were reopening. The priests had started working again with a vengeance, setting up outlying missionary stations along the shore like confetti. Since the church was one of the few buildings spared by the fire that had been set to check the epidemic, the apostolic nuncio had declared a miracle. Leading his flock, Father Huchard headed for the mission. Gone was the time when mass was said in the only priest’s one-room hut, which had been used as a makeshift place of worship, bedroom, dining room, storehouse, and shop. The mission now numbered three priests bursting with health and two buildings made of bamboo, one of which was the school for thirty-two children. A group of African women catechists, with unflattering gray canvas head scarves pulled tight over their foreheads and blouses of the same color flattening their breasts, had set up a table in the courtyard and heartily served a frugal meal of rice, fried fish, and slices of pineapple.

Unperturbed, Celanire jotted down everything she saw in a notebook. She had already used up two thick ones on board the Jean-Bart . The majority of the Sisters of Charity and those of Our Lady of the Apostles disliked this habit of keeping a diary and thought it a sin of pride. But some of the more indulgent among them recalled that Thérèse Martin, in line for canonization, had written her autobiography. The five nuns from Our Lady of the Apostles were destined for a hospital recently opened in Man, way out in the bush. Only Celanire had been appointed to teach at the Home for Half-Castes some thirty miles away in Adjame-Santey. All because of those vows that Celanire had not taken! Since the nuns couldn’t very well stop her from wanting to serve in Africa, they were, nevertheless, adamant she would not be allowed to experience the real hardships of Christian work.

Around midday an army of rudimentarily dressed porters turned up carrying tipoyes, signaling the farewell ceremony. Father Huchard blessed everyone, repeating his last words of advice:

“Be careful what you eat, what you drink, and what you breathe. Beware of the water, the air, and especially the heathens. Those fiends can kill you with their magic.”

He was going straight back to France on the same Jean-Bart . He would pray for them. Celanire bade farewell to her traveling companions as politely and coolly as she had behaved toward them during the voyage. She had never shared their petty enthusiasm, their elation, or their fears. When they told each other secrets, she would cover her ears. Likewise, when they removed their cornets and veils to soap themselves, revealing their pallid skins, she would lower her eyelids out of nausea.

Читать дальше