4. Dorothy Driver, “Transformation Through Art: Writing, Representation, and Subjectivity in Recent South African Fiction,” World Literature Today 70, no. 1 (1996): 45–52, 49.

5. Zoë Wicomb, “Zoë Wicomb Interviewed by Eva Hunter — Cape Town, 5 June 1990,” in Between the Lines II: Interviews with Nadine Gordimer, Menán du Plessis, Zoë Wicomb, Lauretta Ngcobo , ed. Eva Hunter and Craig MacKenzie, 79–96 (Grahamstown: National English Literary Museum, 1993), 80.

6. Ibid., 92.

7. Ibid., 93. Wicomb has explained her “killing” and then resurrecting Mrs. Shenton as an attempt to counter “the stereotypical way in which black women’s writing is viewed” as a autobiographical expression of “our need to air our grievances” (private communication between Wicomb and the author, 15 September 1990; similar comments appear in Wicomb, interview with Hunter, 93). Elsewhere, Wicomb has given a different spin to the mother’s death, suggesting that “the reason the mother doesn’t have an influence is because she is suppressed, she is silenced by the father. Perhaps her reported death in the early stories can be read as her suppression” (interview with Hunter 94–95). See Marais, “Getting Lost,” 38, and André Brink, “Reinventing the Real: English South African Fiction Now,” New Contrast 21, no. 1 (1993): 44–55, 53.

8. Wicomb, interview with Hunter, 93, 84.

9. Ibid., 81, 89.

10. Ibid., 89.

11. Private communication.

12. Wicomb, as quoted in Thulani Davis and Joe Wood, “To Soweto with Love: Black South Africans Respond to the Release of Nelson Mandela,” Voice Literary Supplement, 20 February 1990: 25–26, 26.

13. See Wicomb, “An Author’s Agenda,” Southern African Review of Books 2, no. 4 (February/May 1990): 24; interview with Hunter, 88.

14. Wicomb finds some common ground with Bessie Head, the only other well-known coloured South African woman writer (whose fiction, however, is set in her adopted country, Botswana); see Wicomb’s essays “Shame and Identity: The Case of the Coloured in South Africa,” in Writing South Africa: Literature, Apartheid, and Democracy, 1970–1995 , ed. Derek Attridge and Rosemary Jolly, 91–107 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 96–97, and “Reading, Writing, and Visual Production in the New South Africa,” Journal of Commonwealth Literature 30, no. 2 (1995): 1–15, 10–13.

15. Driver, “Transformation,” 52.

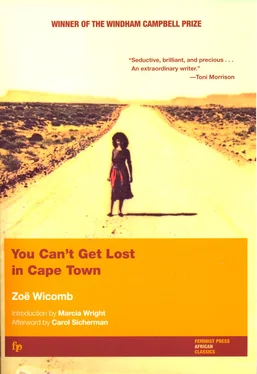

16. Annemarié van Niekerk, review of You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town, Staffrider 9, no. 1 (1990): 94–96, 94.

17. André Brink, “Interrogating Silence: New Possibilities Faced by South African Literature,” in Writing South Africa: Literature, Apartheid, and Democracy, 1970–1995 , ed. Derek Attridge and Rosemary Jolly, 14–28 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 16.

18. Wicomb, interview with Hunter, 84.

19. Lee Lescaze, “Tales Out of South Africa,” Wall Street Journal 11 May 1987: 25.

20. Wicomb’s international audience includes not only those who have read the original text but those who have read translations into other languages — thus far into French, Swedish, German, Dutch, and Italian.

21. Zoë Wicomb, “Culture Beyond Color?” Transition 60 (1993): 27–32, 32.

22. Wicomb, “An Author’s Agenda,” 24.

23. Njabulo Ndebele, whose essays have propelled South African literary redefinitions, identifies the main characteristic of protest writing as “spectacle” that “documents” and “indicts implicitly;. it establishes a vast sense of presence without offering intimate knowledge.” Protest literature, he adds, privileges “group survival” at the expense of “dreams for love, hope, compassion, newness and justice” (Njabulo Ndebele, South African Literature and Culture: Rediscovery of the Ordinary , introduction by Graham Pechey [Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1994], 49–50).

24. Ibid., 58.

25. Lokangaka Losambe, “History and Tradition in the Reconstitution of Black South African Subjectivity: Njabulo Ndebele’s Fiction,” in New Writing from Southern Africa: Authors Who Have Become Prominent Since 1980 , ed. Emmanuel Ngara, 76–90 (London: James Currey, 1996), 76.

26. Ndebele, South African Literature, 50.

27. Wicomb, “Shame and Identity,” 100.

28. Ibid., 96, 100.

29. Zoë Wicomb, “Comment on Return to South Africa” in Into the Nineties: Post-Colonial Women’s Writing , ed. Anna Rutherford, Lars Jensen, and Shirley Chew, 575–76 (Armidale, New South Wales; Mundelstrup, Denmark; Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire: Dangaroo Press, 1994), 575.

30. Judith L. Raiskin, Snow on the Cane Fields: Women’s Writing and Creole Subjectivity (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 229.

31. The United Democratic Front, a coalition of previously existing organizations against apartheid, was formed in 1983. As indicated in the historical introduction, the Black Consciousness movement led politically active coloureds to refer to themselves as black. After Wicomb’s return to South Africa, Brink grouped her with writers who were neither “outside” nor “inside”—“those who were exiled and have returned, bearing in their writing the scars of both experiences” (“Reinventing,” 44).

32. Njabulo Ndebele, Fools and Other Stories (1983; reprint: New York and London: Readers International, 1986), 106.

33. Wicomb, “Shame and Identity,” 105.

34. Boitumelo Mofokeng et al., “Workshop on Black Women’s Writing and Reading,” 1990; reprinted in South African Feminisms: Writing, Theory, and Criticism, 1990–1994 , ed. M. J. Daymond, 107–29 (New York: Garland, 1996), 116.

35. Brink, “Interrogating,” 15.

36. Zoë Wicomb, “To Hear the Variety of Discourses,” 1990; reprinted in South African Feminisms: Writing, Theory, and Criticism, 1990–1994 , ed. M. J. Daymond, 45–55 (New York: Garland, 1996), 47.

37. Verwoerd was assassinated on 5 September 1966. The boycott, a mild demonstration in American eyes, must be seen in historical context. In 1960, the student government of the brand-new University of the Western Cape expired virtually at birth when students refused to accede to administration insistence that whites be seated in front during a student-planned event. The head of the university belonged to the Broederbond, the elite Afrikaner secret society that backed apartheid with enthusiasm. See Nortje, “Staff,” 25–26.

38. Wicomb, “To Hear,” 47–48. Elsewhere, Wicomb says that gender was “ suppressed by the national liberation struggle” (interview with Hunter, 90). Three of the participants in a “Workshop on Black Women’s Writing and Reading” agreed with her, saying: “The women’s struggle and the national liberation struggle need to be waged simultaneously”; one, however, argued that the struggle must be private and domestic because “to stand up on a platform. would be like hanging your dirty linen in public” (Mofokeng et al., “Workshop,” 121–22).

39. References to the Tricameral Parliament, which was instituted in 1984, indicate that the final stories take place around that time. Moira calculates that “ten, no twelve years” have passed since Frieda’s departure (148).

40. Here, it seems, Frieda reflects her creator’s experience: “In the latter half of the book the heroine is in Britain, but I refuse to comment on it because my experience there was about being silent. I was certainly not going to give my heroine any voice in Britain” (interview with Hunter, 87).

41. “Die Stem van Suid Afrika” (“The Voice of South Africa”) is the Afrikaners’ national anthem, celebrating their trek over the Drakensberg; Wicomb discusses the anthem’s author, C. J. Langenhoven, in “Five Afrikaner Texts and the Rehabilitation of Whiteness,” Social Identities 4, no. 3 (1998): 363–83, 369–70.

Читать дальше