IV

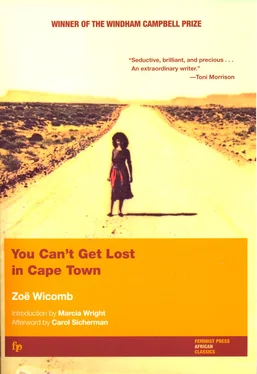

In tracing the story of Frieda’s development, which she tells both pitilessly and sympathetically, Wicomb shows how deeply Frieda has been affected by her inescapable heritage of race, class, and gender. Equally important, Wicomb explores Frieda’s choices: her choice to leave and return to South Africa, her choice to become a writer. It is the adult Frieda, a writer, who narrates the story of her own development and who, in contrast with Wicomb herself, publishes her stories in magazines before assembling them into the book that we read (written, of course, by Wicomb). In the first six stories, up to her departure for England, the writer-to-be at once yearns for self-expression in words and rejects them as “mere escape” or, worse, as “betraying or making a fool of me” so that she cannot “ever tell” the horror she has seen (103, 98, 103) — the horror reflected in the very stories that we are reading. Frieda-the-writer speaks the unspeakable in stories superseding while incorporating the sad anodynes of family stories that “have come to replace the world” (87). By using the first person, “writ[ing] from under [her] mother’s skirts” (172), Frieda refuses “to be nice” and use the third person, a requirement that has so often silenced black South African women. 34Frieda, and Wicomb behind her, invades what Brink calls those “territories of historical consciousness silenced by the power establishments” and their collaborators. 35

Frieda pays a heavy cost in self-conscious misery for her awareness of issues of gender. She knows exactly what is meant when her father talks of resmearing the dusty floors: “he meant I should, since I am a girl” (18). She also knows that she “should be pleased” that she is “not the kind of girl whom boys look at” (21); but boys whistle at her anyhow. Mr. Shenton warns Frieda that servant-hood is the fate of the uneducated; but for educated women there are subtler forms of servitude. While the educated Moira, whom boys do look at, isn’t a servant in the literal sense, she suffers confinement as the subservient wife of a man of inferior mind.

Earlier in the book, in the 1960s, Frieda’s fellow students endorse the argument, openly scorned by Wicomb in her critical writing, that “the gender issue ought to be subsumed by the national liberation struggle.” 36As the male students huddle in the back of the cafeteria, planning the boycott of the memorial service for Verwoerd and whistling at the women, 37they assume (justifiably) that they can exclude the women from the conversation and still obtain their compliance (49–55). Wicomb’s explicitly feminist rejection of such behavior in an essay published three years after You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town is already implicit in her fiction: “I can think of no reason,” she writes in “To Hear the Variety of Discourses,” “why black patriarchy should not be challenged alongside the fight against apartheid.” 38Wicomb’s independence of mind regarding gender parallels her rejection of coloured timidity and acquiescence. Frieda belongs to a racial category whose ambivalence has often led to denial and self-betrayal. Frieda fears that she will be “drawn into the kraal of complicity” (114) and led to defend the “play-white” behavior that she abhors (4).

But it will take time for Frieda to assert her independence from dominant racial and gender definitions. In “A Clearing in the Bush,” Frieda self-consciously “tug[s] at the crinkly hairshaft” of her “otherwise perfectly straight” hair (49) — hair texture being a potent racial and political signifier — and struggles to write an essay on Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles. But she fails to summon up the moral or intellectual strength to contest her professor’s condemnation of Tess. Attracted to Tess’s affirmation of her own moral code in the face of a hostile and denigrating society, and warmed by the “amiable hum” of coloured cafeteria workers, Frieda “wantonly move[s] toward exonerating Tess” (48–49), but she cannot (yet) write subversively. In the end, Frieda’s essay parrots the Afrikaner professor, Retief, who in turn parrots material that he has received from the University of South Africa. By echoing Retief’s party line, Frieda has “branded [Tess] guilty and betrayed [her] once more” (56). She commits this intellectual betrayal — of herself as well as of Tess — at a significant moment in contemporary South African history, on the day after Verwoerd’s assassination. Equally impure, Frieda’s motive for observing the boycott of the memorial service is to gain time to write her overdue essay on Tess.

Frieda’s relationship with Michael, a highly unusual contravention of both custom and law, signals her capacity for social and political rebellion — a capacity barely realized while she remains in South Africa. On one of her “stolen” days with Michael, they go to “Cape Point, where the oceans meet and part. fighting for their separate identities” (75). Out of this emblem of South African race relations Frieda writes a cliché-ridden poem “about warriors charging out of the sea, assegais gleaming in the sun, the beat of tom-toms riding the waters” (75–76). Resembling an exoticizing movie, the poem that “did not even make sense to me [Frieda]” (76) is patronizingly admired by Michael as if it were an art film. In the end, they can neither understand nor liberate one another, and the relationship ends painfully, with Frieda’s abortion.

Several years later, recognizing that she must literally go far in order to achieve self-understanding and self-expression, Frieda resolves to emigrate, despite her family’s disapproval. In the ironically titled departure narrative, “Home Sweet Home,” she mocks the family icons and tells two stories that she must conceal from her family. The story about a mule caught in quicksand connects with the social and political themes of the book. Under the pretext of a sentimental visit to the landscape of her childhood, Frieda leaves the family gathering in order to escape their words of self-betrayal and complicity. Her protective father, warning predictably against puff adders, is oblivious to the impalpable sociopolitical danger symbolized by the quicksand that fatally sucks in the unwary. The story ends with a terrifying emblem of a sterile people doomed by its inability to resist. Its hind legs sinking into the quicksand, the mule brays, struggles, and then

balances on its hind legs like an ill-trained circus animal, the front raised, the belly flashing white as it staggers in a grotesque dance. When the hind legs plummet deep into the sand, the front drops in search of equilibrium. Then, holding its head high, the animal remains quite still as it sinks. (103)

The dignified acquiescence of the mule as it dies vainly seeking equilibrium suggests the attitude of Frieda’s family and the reason for her exile. She must distance herself from their acceptance of the fate imposed by South African history. She also leaves to escape the apocalypse hinted at in the changed landscape, for she is wrong to think that “in the veld you can always find your way home” (73). Instead of “landmarks blaz[ing] their permanence” (73), she discovers a landscape altered by a tumultuous flood “more forceful than anything I’d ever known as a child” (92). The new landscape bespeaks horror: the “swirling” flood of black rage that will alter the South African political landscape beyond recognition.

During the twelve years of Frieda’s exile, which conclude in the mid-1980s, 39that rage has expressed itself. In the interim, Frieda has felt like “a Martian” in England, where the view from her window shows not Hardyesque “bright green meadows” but “lurid yellow of oil-seed rape sag[ging] like sails under squalls of rain” (123, 90, 112). 40Back in a South Africa tense with black resistance, Frieda is ready both to speak the unspeakable and to see with a new clarity of vision.

Читать дальше