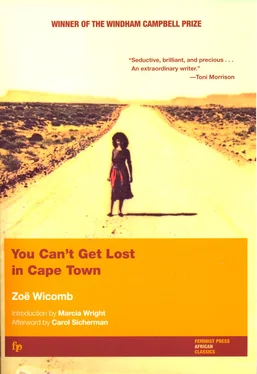

Meanwhile, in the United States, critical reception has been so warm as to disconcert the author herself. 18Reviewers couched their praise in terms common in Western intellectual response to literature from the so-called Third World: the book was read not so much as fiction but as a useful report from an “exotic” land. No doubt, as Lee Lescaze writes in the Wall Street Journal , “Americans can learn a good deal about South Africa” from this book, 19but such benefits are a byproduct rather than the purpose of reading good literature. Writers like Wicomb must send their works out to an international readership, 20some of whom experience discomfort in encountering the unfamiliar. This Feminist Press edition seeks to encourage a more subtle reading of Wicomb’s restrained and oblique stories, in which even the tiniest detail may hint at the emotional valences created by apartheid. A homely milk separator may become an emblem: “Out of the left arm the startled thin bluish milk spurted, and seconds later yellow cream trickled confidently from the right” (5).

III

You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town at once encapsulates particular moments of apartheid South Africa and, given the still-present legacy of apartheid, remains relevant to the country as it exists today. In both her fiction and her essays, Wicomb strives to make the reader aware “not only of power but of the equivocal, the ambiguous, and the ironic. embedded in power.” 21The proper function of literature, as she argues, is to offer the reader “the experience of discontinuity, ambiguity, [a] violation of our expectations.” 22

A country so long riven by multiple and institutionalized divisions cannot reconstitute itself as a unity simply by adopting a constitution and running democratic elections. As indicated in the historical introduction, apartheid legislation deprived most South Africans of benefits of citizenship that are taken for granted in democracies. As a result, until recently, writers from disenfranchised groups have tended to produce “protest” literature aimed at displaying the effects of apartheid upon those excluded from participation in civil society. 23

By the early 1980s, however, protest literature and the wider anti-apartheid movement had successfully informed the world, freeing the imaginations of post-protest writers like Wicomb and Njabulo Ndebele to offer the subtle details of their “intimate knowledge” in what Ndebele calls a “rediscovery of the ordinary” that will foster “the growth of consciousness.” 24In fact, despite obvious differences in subject matter and perspective, many aspects of Wicomb’s stories can be described in the same terms as Ndebele’s own: they are, as Lokangaka Losambe notes, “internal and deeply rooted in the daily life of the oppressed,” 25manifesting, as Ndebele himself writes, a “dialogue with the self” that features “the sobering power of contemplation, of close analysis, and the mature acceptance of failure, weakness, and limitations.” 26

For all these similarities, there is a radical difference between Ndebele’s subject matter and Wicomb’s — differences stemming from Ndebele’s black identity and Wicomb’s coloured identity. While the characters in works by Ndebele and other black contemporaries strive to recuperate black collective history, Wicomb’s characters find their “roots in shame” about coloured historical origins in miscegenation and slavery. 27From these roots grew “coloured complicity” in hiding their “Xhosa, Indonesian, East African, or Khoi origins,” as well as their enslavement. 28This led in turn to a shameful coloured “history of collaboration with Apartheid.” 29The effect of Wicomb’s work is to condemn this complicity by coloured people, especially those with more education and power. But she is not without compassion for the characters who seek a modicum of power and “respectability” at the expense of blacks and “inferior” coloureds; the trap they have fallen into is one set by apartheid.

In “Shame and Identity,” Wicomb signals her own complex attitude: she uses our to characterize coloured complicity with apartheid. In so doing, she asserts imaginative sympathy with attitudes that she condemns intellectually — sympathy in its root meaning of “suffering with.” Such sympathy is the essential ground of her ability to imagine, without condemning, Skitterboud’s obedience to his “baas” (master) and Tamieta’s baffled presence at the memorial for Verwoerd. The adult Frieda who narrates the book recognizes her student self as too limited to perceive Tamieta as ours ; by the time she returns from England, us and them are close enough for her to hear the rich nuances of Skitterboud’s story.

In You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town , Frieda’s task is to work toward an ability to accept our rather than their as a pronoun for coloured people — and in the end, her black compatriots as well. This task requires a humility at variance with the superiority inculcated by her anglophile relatives. Frieda’s conflict with her mother makes our even more problematic; for, in addition to the expectable mother-daughter competition, she must contend with a mother who encapsulates the social snobbery of upward-striving coloured people. The young Frieda follows her mother’s dictates, but at the same time she uses they and their to distance her own family: she wants to destroy the “wholeness” of “their stories, whole as the watermelon” (87). Until the final story, the mother stands for everything that the adult Frieda reviles, teaching her child what Judith L. Raiskin has described as “English and the cosmetics of self-hatred.” 30

Wicomb has a surprise in store for readers who think they have sorted out our and their and my , who think they know the mother depicted in “Bowl Like Hole” and “Behind the Bougainvillea.” When Mrs. Shenton apparently dies of respiratory illness, and Little Namaqualand offers the child no alternative female role models of appropriate education and status, Frieda must depend on her father’s judgment. Echoing her mother’s insistence on rising above her station, Mr. Shenton presses his daughter to leave home and further her education: “‘You must, Friedatjie, you must. There is no high school for us here and you don’t want to be a servant. How would you like to peg out madam’s washing and hear the train you once refused to go on rumble by?’”(24). Ensuring Frieda against sexual advances that might compromise her future, Mr. Shenton stuffs her with delicacies “marbled” with fat; compliant, she “eat[s] everything he offers” (24). Small wonder that Frieda-the-writer kills him off in the same story, “A Trip to the Gifberge,” in which she takes a drive with her newly appreciated mother, tracing a route laid out — but never taken — by the father.

The final story suggests that knowledge of Griqua history may help an unashamed Frieda to identify in the future with the plight of coloured people, and even identify with black resistance. Shame has driven both her exile and her return to face her mother’s challenge to embrace her people’s history. Such an embrace, as the historical introduction explains, was made possible by the Black Consciousness movement, which took place during Frieda’s years in England and which enabled the renewed alliance across racial lines represented by the United Democratic Front. 31Coloured intellectuals like Nortje and Wicomb could find encouragement in the view of black intellectuals like Ndebele that “history will always clean your soul,” as a wise uncle tells his nephew in one of Ndebele’s stories. 32The prerequisite for such a cleansing exists in Wicomb’s unblinkered vision. If coloured South Africans accept their own “multiple belongings” with pride, Wicomb proposes in “Shame and Identity,” their shame will dissipate. 33

Читать дальше