konfyt

melon preserve

kooigoed

bedding

koppie

small hill

kyk

look

lekker

nice, good

mealie

corn

mebos

dried-apricot confection

meid

girl (derogatory)/servant

melktert

custard tart

miskien

perhaps

moffies

homosexuals (derogatory)

Môre

Good morning

Old Cape Doctor

southeasterly wind

Oom/Oompie

Uncle (respectful form of address)

ounooi

female employer; white madam

oupa

grandpa

ousie

respectful term for older woman

pasop

watch out; be careful

plaasjapie

country bumpkin

platteland

rural areas

pondok/pondokkies

shack/little shacks

roeties

unleavened Indian bread

shebeen

unlicensed drinking place

sies

expression of disgust

skollie

hooligan

Slamse

derogatory term for Muslim

sousboontjies

stewed bean dish

soutslaai

a succulent (ice plant)

stamp-en-stoot

dish of beans and mealies (colloquial)

stoep

a small platform with verandah at the entrance to a building

tokolos

evil mythical creature

Vaaljapie

cheap locally produced white wine

veldskoen

stout shoe made of crude leather

vetkoek

flat bread fried in oil

vygies

a succulent related to the fig

ysterbos

bush, shrub

p. 114: ‘Kosie, gebruik jy alweer my tyd om to skinder. Waarom moet julle kaffers tog so skree. So ’n geraas in die hitte gee ’n beskawe mens ’n kopseer.’

‘Kosie, don’t use my time for your gossiping. Why do you kaffirs have to shout like this. Such a racket in the heat gives a civilised person a headache.’

p. 177: ‘Suikerbossie’k wil jou hê/Wat sal jou Mamma daarvan sê. ’

A popular folk song in which a girl is affectionately called a protea

I

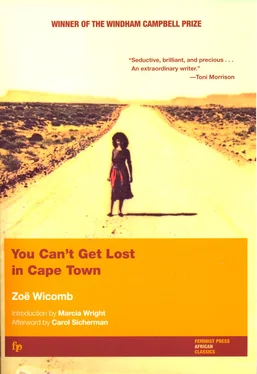

You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town is remarkable both for its high literary achievement and for its unique status within South African and, indeed, world literature: it is the first book-length work of fiction set in South Africa by a coloured woman writer. 1Although the book is not autobiographical in any but a superficial sense, the background of the protagonist, Frieda Shenton, is that of her creator, Zoë Wicomb, whose brave imagination has set before us a discomfiting heroine — frank, sometimes amused, often uncertain. Through ten connected stories, Wicomb offers a portrait of her protagonist’s coming of age as a coloured woman and as a writer. Race and gender, shaped by the historical complexities of South Africa, profoundly affect Frieda’s experiences and perspective, as well as her development as a writer.

This essay explores the unstable nature of Wicomb’s narrative and the shifting identities of her characters as it traces Frieda’s development from a sharp-eyed child eluding her mother’s control to a mature woman capable of re-visioning her mother and her world. The little Frieda whom we first glimpse crouching under a kitchen table is a keen observer, too young perhaps to feel burdened by the weight of history, yet already aware of the politics of class and color that shape her family and community. Frieda-the-writer, wryly refracting her thirty-year-old memories through the lenses of her adult self, never loses touch with the naïve and revealing vision with which her child self once observed the world.

Frieda’s world is a violent world, in a violent state of flux, even though violence as such is only glimpsed. The cumulative effects of centuries of oppression mark her from the very year of her birth, 1948, the year that the National Party took power under the slogan of apartheid, the doctrine of a forcibly maintained “apartness” of races. Wicomb’s amused interest in the varieties and oddities of her characters’ attitudes tempers the inherent grimness of her subject matter. Her mingled tones are evident the title of the first story, “Bowl Like Hole,” which calls attention to the twin absurdities of apartheid and the English language. “Bowl” is pronounced like “hole,” not like “howl”; and no one howls with grief in this nonetheless deeply painful book.

No one should miss Wicomb’s astringent wit. Little Frieda peeking “through the iron crossbars of the table” sees her mother’s “two great buttocks” as representing “the opposing worlds she occupied” (4). No child would draw such a comparison, of course; it is the adult narrator who amuses herself with the interpretation, at the same time hinting at the profoundly oppositional nature of life in South Africa. Other early examples of humor are situational, as when Mr. Shenton and the driver battle to open the car door for Mr. Weedon (3); or when Mr. Shenton gamely carries on a two-way conversation by assuming responses from his silent cousin, Jan Klinkies (18); or when Tamieta, at the memorial for the assassinated Prime Minister Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd, listens to the rector’s “Ladies and gentlemen” and thinks: “Yes, it is only right that she should be called a lady. And fancy it coming from the rector. Unless he hasn’t seen her” (59). 2Wicomb satirizes such pretensions, but at the same time suggests what lies beneath them — a desire for dignity and recognition in a world that renders most of its inhabitants invisible.

Wicomb also makes sure to alert her readers even before page one to a dominant tone of seriousness. Epigraphs warn that “trouble” lies ahead in this “history of unfashionable families” and signal as well Wicomb’s multiple intellectual origins, for she chooses the coloured South African poet Arthur Nortje 3and the English novelist George Eliot. Like Nortje himself, Wicomb disregards the warning in the second epigraph; she takes us “beyond /. the intimate summer light / of England” to the barren landscape of Little (or Klein) Namaqualand. In Eliot’s ironic words, these stories about “respectable” people disregard “the tone of good society.” On the very first page, we observe a group of children engaged in “unfashionable” activities: they “empt[y] their bowels and bladders” in the bushes or gape with “their fingers plugged into their nostrils.”

As the children gaze “with wonder and admiration” at “the magnificence” of Mr. Weedon’s Mercedes — representing the routinely exercised power of the minority whites — the adult Frieda, in a characteristic narrative attitude, allows us to understand her characters’ perceptions, even as we are distanced from them. Conflicting points of view mark the narrative from the start, as Frieda endeavors to become independent of the debilitating class and social stereotypes, perpetuated by apartheid, that deform coloured vision. The Shentons’ belief that their single English ancestor raises them higher than other Afrikaans-speaking coloureds painfully illustrates the internalization of white values. English-speaking Mr. Weedon is, in Mrs. Shenton’s whispered words, “a true gentleman,” from whom the contemptible Afrikaans-speaking Boers “could learn a few things” (3). The Boers, or Afrikaners, are the whites to hate; and because history made Afrikaans the mother tongue of most coloureds, to speak English is, in part, to defy Afrikaner authority. As noted in the historical introduction, both language and constructions of ethnicity are deeply tied to class. In her regard for the English, Mrs. Shenton is expressing such class distinctions, as we see when she praises “civilised” Mr. Weedon because he employs a “registered Coloured” driver so light-skinned as to appear white (4).

A good deal of Wicomb’s wit emerges from slyly contrasting points of view; her skill lies in creating various points of view, while permitting Frieda to move gradually toward increasingly aware and more consistent adult perceptions. As “Bowl Like Hole” proceeds, the narrative expands beyond Frieda’s immediate realm, moving beyond the schoolyard and from beneath the kitchen table, to follow Mr. Shenton’s and Mr. Weedon’s trip to the mines. Wicomb creates Mr. Weedon’s point of view — his “deep fear of appearing foolish” before the coloured miners, his awareness of the “disgust” that lies behind their apparent deference — as well as Mr. Shenton’s temporizing as he omits translations of Weedon’s more foolish comments (7–8). Certainly there is humor in Mr. Shenton’s omissions and in the Shentons’ puzzlement over the inconsistencies of English pronunciation. The imperfection of their understanding calls into doubt the rightness of any single point of view, including Frieda’s.

Читать дальше