A healing of the wounds of apartheid depends on vision, and it is with literal, as well as figurative, vision that “A Fair Exchange” begins and ends. At the beginning, Meid remembers a girl who was “not blinded but struck dumb” when she looked defiantly at the midday sun (125). Wicomb hints at, then spares Frieda such a fate: defiance punished not by lack of vision but by lack of words to express the nearly unspeakable pain that she observes. The final section reveals that Frieda has written the illiterate Skitterboud’s story, illustrating a type of representation common in societies in which many people are not literate. Frieda gives Skitterboud her glasses, and he gives Frieda his story: it is “a fair exchange.” If Frieda can retain Skitterboud’s lesson that he knows more than “experts” (140), she will be worthy of writing his “terrible stories” (182).

To prepare Frieda for Skitterboud’s story, an ambiguous image of glasses appears in the preceding story, “Behind the Bougainvillea.” As she sits outside in the dust — her position disproving the figuratively blind Mr. Shenton’s assurance that the newly “civilised” Boers permit coloured patients in the doctor’s waiting room (105) — she sees her own face, “bleached by an English autumn,” reflected in the “round mirror” of a fellow patient’s dark glasses (111). She averts her gaze and buries herself in a novel, finding not escape but “shame” in the English author’s racism. Soon after she complicates her own position further by submitting sexually to the “stranger” of the dark glasses, having recognized him as Henry Hendrikse, a friend of her youth turned either revolutionary or government spy. The unresolved contradiction baffles the reader, who does at least know that he is the very same Henry whom her father had reviled years ago as “almost pure kaffir” (116). Perhaps inspired by his African darkness, he has learned to speak Xhosa, which Frieda mistakes for Zulu.

Frieda is too newly returned, too out of touch with changes, to figure out Henry’s relationship to the apartheid government, whether he is its enemy or its tool. The deliberate lack of clarity is unsettling, and intentionally so. Ending the story with Mr. Shenton’s naïve question “[W]hat would the government need spies for?” (124), Wicomb wants her readers to experience the unspoken answer with the force of the mental “dynamite” of Frieda’s “terrible stories” (182): this is a government built on spies and murderers. Frieda’s cousins, “all UDF people,” need no glasses to see the official cruelties to which Mr. Shenton is blind (170). By the time the book closes, Frieda is on the verge of her cousins’ insight.

Frieda sees many things with new insight, nothing more so than her own mother. She brings her mother the same bunch of proteas, the official South African national flower, that her aunt has presented at the airport as a welcome-home gift, provoking Frieda’s “revulsion” (165). Staring down at the proteas, the mother “has never seemed more in control,” and we remember why Frieda has had to escape. Now, however, she receives the proteas and “leans them heads down like a broom against the chair” (169–70).

In “A Trip to the Gifberge,” the mother, though still at times harsh, is different from the rigid, censorious woman whom Frieda has “killed” in her stories. Whereas in earlier stories Mrs. Shenton kowtows to the Englishness in her husband’s family, now she burns with long-remembered anger at the contemptuous epithet “Griqua meid” (165) bestowed by her father-in-law. Can this be the mother who disparages little Frieda as a “tame Griqua” (9)? The mother has Griqua eyes and cheekbones that contest the “curious high bridge” of her nose that is her European heritage (164). At the end, mother and daughter acknowledge with pride their Griqua forebears who inhabited the interior of the Cape when the Dutch pushed northward in the eighteenth century.

Mrs. Shenton becomes a thematic vehicle for Wicomb’s view of South Africa as she and Frieda travel up into the mountains, reclaiming both land and ancestry, in a journey that mockingly emulates the Griqua trek over the Drakensberg in 1861. When she disputes Frieda’s arrogant doubt that proteas grow in the mountains, she is proven right. Her plan to take a bush back for her garden provokes predictable scorn in Frieda: “‘If you must,’ I retort. ‘And then you can hoist the South African flag and sing “Die Stem”’” (181). 41Mrs. Shenton lays claim to her Griqua heritage, to the land and to the proteas, with a comprehensive vision that silences Frieda:

“You who’re so clever ought to know that proteas belong to the veld. Only fools and cowards would hand them over to the Boers. Those who put their stamp on things may see in it their own histories and hopes. But a bush is a bush; it doesn’t become what people think they inject in it. We know who lived in these mountains when the Europeans were still shivering in their own country. What they think of the veld and its flowers is of no interest to me.” (181)

Arguing for the priority and neutrality of nature, and asserting Griqua knowledge of the land, the mother again surprises us; once an Anglophile, she now finds European models irrelevant. And Frieda — acknowledging her “ancestors who roamed these hills” (172), having told her “terrible stories” (182) — moves toward a closer understanding of her roots.

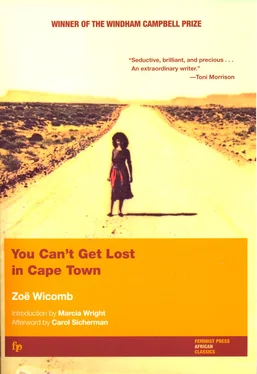

Returning to South Africa after her father’s death, Frieda-the-writer finds herself freed from the eager cringing before European authority and the culpable naïveté that have accompanied his loving indulgence of her. 42By the end of the book, Frieda feels that there might be a space for her in Cape Town, where — through writing — she would continue “playing with dynamite” (182). When the narrative ends with Frieda’s mother’s question, “But with something to do here at home perhaps you won’t need to make up those terrible stories hey?’”(182), the effect is both rhetorical and ironic. For in bringing forth her brave heroine and in depicting her struggle to find her place as a coloured woman and a writer, Wicomb has paved the way for more stories to be told.

Carol Sicherman

Pleasantville, New York

December 1999

NOTES

This afterword draws, with the kind permission of the publishers, on two of my previously published essays: “Zoë Wicomb’s You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town : The Narrator’s Identity,” in Black/White Writing: Essays on South African Literature, ed. Pauline Fletcher (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press; London and Toronto: Associated Universities Press, 1993); and “Zoë Wicomb’s You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town : A New Clean Voice,’” in Nwanyibu: Womanbeing in African Literature, ed. Phanuel Akubueze Egejuru and Ketu H. Katrak (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1997).

1. For the handling of coloured, see the historical introduction to this edition, note 1.

2. In the same mingled vein of serious wit, the narrator remarks that “a tapeworm cannot protect me forever” (40). The allusion is to the adventitious reprieve given to her overdue essay by Verwoerd’s assassin, who claimed that a tapeworm had urged him to kill the prime minister (see note 37).

3. The first epigraph comes from Nortje’s “Waiting”; the second, from “Immigrant” (in his posthumous volume Dead Roots: Poems [London: Heinemann, 1973], 90–91 and 92–94 respectively). Just six years older than Wicomb, Nortje attended the University of the Western Cape, went into exile in England and Canada, and committed suicide at twenty-seven (Hans M. Zell, Carol Bundy, and Virginia Coulon, eds., A New Reader’s Guide to African Literature , 2d ed. [London: Heinemann, 1983], 437–38). See Nortje’s two essays about the University of the Western Cape, “The Staff” and “The Students,” in Arthur Nortje and Other Poets, 23–31, 8–11 (Athlone, South Africa: Congress of South African Writers, 1988). For an analysis of Wicomb’s use in “Ash on My Sleeve” of the final line of Nortje’s “Waiting” (“the night bulb that reveals ash on my sleeve”), see Sue Marais, “Getting Lost in Cape Town: Spatial and Temporal Dislocation in the South African Short Fiction Cycle,” English in Africa 22, no. 2 (1995): 29–43, 38–39. Wicomb seems to allude to Nortje in her story “In the Botanic Gardens,” in which the apparent death by suicide of a humble South African mother’s brilliant son, Arthur, brings her to Glasgow (“In the Botanic Garden,” in The End of a Regime? An Anthology: Scottish-South African Writing Against Apartheid, ed. Brian Filling and Susan Stuart, introduction by Emeka Anyaoku, 126–34 [Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1991]).

Читать дальше