I have undergone a little over ten years of various forms of captivity, agitated in seven countries, and written twenty books. I own nothing. On several occasions a press with a vast circulation has hurled filth at me because I spoke the truth. Behind us lies a victorious revolution gone astray, several abortive attempts at revolution, and massacres in so great number as to inspire a certain dizziness. And to think that it is not over yet. Let me be done with this digression. Those were the only roads open to us. I have more confidence in humankind and in the future than ever before.

However, Serge’s pessimism of the intellect came out in his private journals, letters, and fiction. In a 1946 letter, he opines that the world “after a period of dark struggles and anxieties, may succumb to a terrible conflagration” and compares the “shock” of modern weapons of mass destruction to “cosmic phenomena.” “Today, all explosives have attained such power that their effect is no longer on a human scale.” In his Notebooks , he reflected that “Trotsky correctly foresaw that we might enter a phase of uninterrupted, permanent warfare if humanity does not achieve a social (and psychological) reorganization, the means to which appear, realistically, pitifully weak.” There was not much time left either: “For technological reasons, decisions [about society’s future] can not be put off indefinitely.” Yet such social changes depend on intellectual clarity, on critical thinking, which Serge increasingly saw both as impotent in the face of mass social conditioning and as threatened with outright extinction: “Destroy a few brains, quickly done! ” And if they are the few thousand brains that understand Einstein, Freud, or Marx?

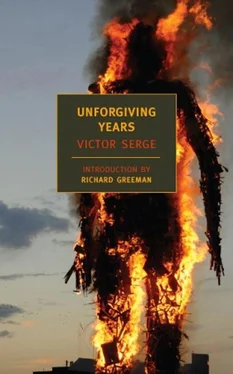

These pessimistic visions inspired Serge’s “terrifying” novel about “the problem of consciousness in time of war.” The imagery of the chapter titles and the poems placed at their heads evokes planetary catastrophe (“the central fire,” “lightning,” “smoking rains,” “naked dawns”). A Russian soldier wonders that “they haven’t invented war toys to split open the planet yet.” A German soldier reflects: “There are no warriors anymore: only poor bastards facing exploding volcanoes. The cosmos has gone berserk…. He was…alive, living under the cold light of a huge, dark, sulfurous star: the sun of destruction.” The Berlin section opens in an underground shelter where the thunder of bombs sends “huge waves through the earth.” “Brigitte, Lightning, Lilacs” is full of images of dreams, geological eruptions, and buried civilizations like Pompeii and Atlantis. Serge had to invent a neologism, “pan-destruction,” to express the scale of the devastation.

Nowhere was the destruction so total as in Germany. Serge fearlessly depicted Germany’s defeat from the point of view of ordinary middle-class Germans seen principally as victims. This viewpoint is only now being legitimized sixty years later with a reexamination of the unparalleled destruction of German civilian cities by the Anglo-American bomber command and the publication in Germany of World War II memoirs and diaries. Serge satirized the cliché of German collective responsibility in the figure of an arrogant, overfed American journalist who drives up to a bombed-out Berlin neighborhood in a jeep and asks the uncomprehending survivors — whom Serge compares to “inhabitants of Chicago’s slums” — if they feel guilty.

As distinct from the rich and powerful Germans, whose country estates were largely untouched by the war, Serge portrays ordinary Germans as more or less good people who patriotically believed what the government and the media told them (like many Americans today). As he explained in a letter to Macdonald: “People are caught up in the gears [of the social machine…] Nothing mysterious about it.” For Serge, neither the German soldiers killed and mutilated at the front nor their starved, bombed-out, and mass-raped mothers and sisters were “responsible” for the war. Indeed, the Nazis and industrialists who started it needed first to arrest thousands of German trade unionists, socialists, Communists, and conscious-stricken Christians like Brigitte’s fiancé. These were the Germans he had lived with and written about twenty years earlier in Witness to the German Revolution.

Serge symbolized German innocence in the angelic figure of Brigitte, a gentle, cultivated, middle-class girl, orphaned by the war and driven to Ophelia-like madness by the death at the front of her beloved fiancé (shot by the SS for questioning the war). A midnight bombing raid draws the ecstatic girl to the roof. We see her frail figure silhouetted against the constellations and the “lightning” of explosions: “The whiteness wove a tissue of radiance around the city, around the entire planet: the planet in her wedding dress. A bright cupola rose high above Brigitte’s rapt, thrown-back head.” When she is found mysteriously strangled, a neighbor picks some lilacs that have miraculously survived the bombings — testimony to “the power of simple vegetative life” — and lays them next to her fragile body. Alain, the artist, sees her as “Botticellian,” and her image returns in his delirious meditations on the nature of beauty and art which conclude the German section.

The final movement, “Journey’s End,” returns to the question “What to live for?” by posing another: “What will endure, when it all blows up, melts down, or grinds to a sulfurous halt?” It opens with an invocation:

And let fall the smoking rains

over the cerebral forest!

So many funeral masks

lie preserved in the earth

that nothing yet is lost. [22] 22. The image of “smoking rains” probably came to Serge after witnessing the birth of the volcano Parcutin in 1943 under a rain of hot cinders which ignited and buried the surrounding dwellings and forest. They also refer, of course, to explosives raining from the sky which destroy the “cerebral forest” of human consciousness — seen as if rooted in the earth like a great living brain. Yet the poet’s attitude to this destruction is one of consent, for “nothing yet is lost.” Not as long as the earth preserves “funeral masks” — artefacts of dead cultures like the Aztecs and Mayas he wrote about in Tombeau des civilisations.

Serge’s “funeral masks” suggest that enduring works of art can preserve the content of human consciousness from oblivion — even after the destruction of whole civilizations. They may point as well to works of literature which successfully “capture the moment” — thus winning their author a kind of immortality. But these are forlorn hopes. In Birth of Our Power , his 1930 novel about a failed workers’ uprising in Barcelona, Serge had confidently written “Nothing is ever lost” — correctly anticipating the coming Spanish revolution of 1936. The 1946 version “nothing yet is lost” signals a change of historical perspective to archaeological time and from social progress to art.

It is in art that Alain, now disillusioned about Russia, finds his solution to the problem of “what to live for.” Daria is still seeking a solution of her own as she crosses the Atlantic and makes her way to join Sacha/D/Bruno Battisti at his remote coffee plantation in rural Mexico. However, instead of discoursing on politics and history with her, Sacha tells her about his life in Mexico, about its ancient peoples, who “lived in an unstable cosmos, as we live in an unstable humanity armed with cosmic powers”; about its seasons, the annual death of the sun-parched earth and its irresistible luxuriant rebirth under the violent rains and lightning storms of the spring. In response to her horrifying account of the bombing of Berlin, he leads her to a banana tree and points to its “violet-tinted, powerfully-sexed turgidity.” His consciousness, free of the imperative of historical integration, has led him to this final affirmation: “All that exists cries, whispers, or sings that we must never despair, for true death does not exist.”

Читать дальше