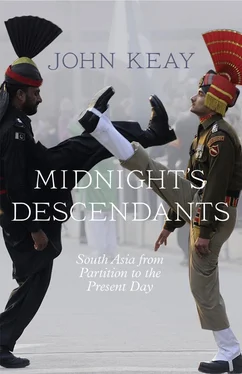

There are subtle but significant differences between the notions of communal autonomy and territorial sovereignty. The first emphasizes the rights of the people of a community to self-determination, rights which could in theory be achieved within a single state. The second stresses the bounded space within which a community is sovereign and could be realized only by a territorial separation. 7

In the last hectic months of British rule, when parts of the country were already beset by sectarian massacres, sovereignty alone seemed to safeguard communal autonomy, with fixed frontiers being its surest guarantee. Yet sixty-five years later, communal discord within and between the post-Partition states of South Asia is more acute than ever. ‘Whenever there is a riot in India, we suffer here,’ says a spokesperson for the Hindu minority in Bangladesh. 8Whenever a Pakistan-trained terrorist opens fire in India, India’s Muslims come under suspicion; and whenever India’s Hindu nationalists vent their spleen on the internet, more Pakistani and Bangladeshi Muslims sign up for jihad . Just as the tides, the migrants and the hawk-eagles come and go unchecked across the Sundarbans, so the tit-for-tat of outrage and retaliation ricochets along the 7,000-kilometre length of those brave new frontiers ordained by Partition’s insistence on a territorial separation.

Over the last half-century the shadows of Partition’s brutal dislocation have grown ever longer. They slant across the whole course of events in post-Independence South Asia. Some observers liken Partition to a nuclear explosion whose lethal fallout will go on being felt for generations to come. Others see it as a recurring natural phenomenon that, having severed the subcontinent, then ( de facto ) the disputed state of Jammu and Kashmir, and then the two-part Pakistan, is ever-ready to strike again. Nearly all see it as unfinished business. Every war, near-war and insurgency fought in the subcontinent since the end of British rule owes something to the legacy of Partition. And so long as this sore festers, any ‘normalising’ of relations between the partitioned states proves elusive.

Elsewhere in the world various political unions, defence pacts, free-trade associations and hegemonic doctrines (Monroe, Brezhnev, etc.) have lent some coherence to the conduct of international relations. In South Asia, a region where geography, history, economics and culture all argue strongly in favour of the closest possible association, even modest attempts at regional cooperation flounder. The subcontinent continues to be defined not in terms of shared interests but of past traumas, contested loyalties and irreconcilable ambitions. Encouraged by governments of every hue, national identity still owes much to an obsessive awareness of the hostile ‘other’ just across the border. Antagonism reigns, officially.

This ‘othering’ extends even to ideology. Each successor nation presents a political profile that seems to challenge that of its neighbour. The Republic of India is secular, democratic, internationally respected and increasingly regarded as an economic success. Pakistan and Bangladesh, on the other hand, are determinedly Islamic, susceptible to military rule, internationally disparaged and economically struggling. (Nepal and Sri Lanka, the other sizeable components of what scholars now prefer to call ‘South Asia’ rather than ‘the Indian subcontinent’, are currently too traumatised by recent civil wars to be easily categorised.) Partition did not just divide most of the region: it launched the successor states on such diametrically opposed trajectories that to this day South Asians commonly prioritise ‘Partition’ over ‘Independence’. The second half of the twentieth century is not the ‘post-Independence era’; it is the ‘post-Partition era’. The euphoria of freedom has been silenced by the shock of division.

The consequences of this division are critical, and not just for South Asia. By 2020 India will have the largest population in the world, and South Asians as a whole will comprise a quarter of the people on the planet. Nor, on the grounds of negligible disposable income, can these numbers any longer be discounted as a statistical irrelevance. Already India’s middle class is one of the world’s most numerous, and its corporate sector includes more multinationals and generates more billionaires than anywhere else in Asia except China. The world’s largest market and its largest pool of unskilled labour is rapidly becoming its largest reservoir of innovation and expertise. South Asian excellence now extends to everything from pharmaceuticals and telecoms to finance, info-technology and prize-winning literature.

It also includes rocketry and a terrifying military capability. With both India and Pakistan in possession of nuclear weapons, with neither eager to submit to international controls and with China’s nearby arsenal dwarfing both, the potential for a nuclear conflagration is here all too real. What may be the most promising zone in terms of the world economy is located in what US analysts have dubbed the most dangerous arena on earth.

Worldwide, South Asians account for two out of every five Muslims; and of these nearly as many have their roots in India as in Pakistan or Bangladesh. Through them, Islam’s international grievances (over Palestine, Iraq, Afghanistan and anywhere else within range of a drone) get internalised in South Asia; and through them and other disaffected parties, South Asian grievances (over Balochistan, Nagaland, numerous other hotspots and above all Kashmir) get externalised in the West. The blood-letting occasioned by a dispute about a mosque in Uttar Pradesh can surface in the British House of Commons. Confrontations in the high Himalayas can bring the world to the brink of armageddon.

Yet to the outside observer South Asia’s peoples seem to have a lot more in common than not. In the world’s departure lounges they are as ubiquitous and just as hard to allocate to a particular part of the subcontinent as the Chinese. Regardless of nationality, they look not unalike, they often wear loose, baggy attire, and they travel with too much luggage. They are also rather particular about their dietary preferences. They converse in languages (including English) some of which are mutually comprehensible. They enjoy the same movies and opt for the same music channels. Nearly all admit to regularly engaging in some form of devotional activity, nearly all marry within approved circles, and nearly all take pride in their familial, communal and regional identities.

Down on the ground, were it not for the border fence, you could still pass from India’s West Bengal into Bangladesh without realising you had changed countries; likewise from the Indian states of Rajasthan and Punjab to the Pakistani provinces of Sind and Punjab (each country has a Punjab, because the British province of that name was itself partitioned). The differences between one country and another are much less obvious than those between most adjacent European states. Non-Islamic India is still home to nearly as many Muslims as either Pakistan or Bangladesh. Hindu women may cover their faces like their Muslim sisters; and Pakistani men may wear pyjamas like their Indian brothers. Despite its newly trumpeted affluence, India still has more of the malnourished, the unlettered and the socially deprived than Pakistan and Bangladesh combined. Even the excitement over its growth rate may be deceptive. Only twenty years ago it was Pakistan that was slated to join the Asian periphery’s ‘tiger economies’. Thirty years ago it was Sri Lanka. What one economist has called ‘persistent orderly hunger’ is one of the region’s shared and all-too-enduring characteristics.

So too is the confidence born of a deep and incredibly rich matrix of tradition and devotion. Here globalisation comes wreathed in garlands and incense. A podgy Ganesh presides in the boardroom; temple and waqf are quoted on the Mumbai stock exchange. In Muslim areas night turns to day during Ramadan. Everywhere matrimonial expenditure chomps into GDP. Pride in the past, an unshakeable sense of one’s community and a dazzling array of cultural references are not peculiar to the region. But in South Asia their resilience and centrality is second to none.

Читать дальше