INDIA

DISCOVERED

The Recovery of a Lost Civilization

JOHN KEAY

HarperCollins Publishers 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 1981

First published in paperback by William Collins 1988

Copyright © John Keay 1981

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollins Publishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007123001

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2010 ISBN: 9780007399642

Version: 2015-06-17

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

List of Illustrations

Introduction

CHAPTER ONE This Wonderful Country

CHAPTER TWO An Inquisitive Englishman

CHAPTER THREE Thus Spake Ashoka

CHAPTER FOUR Black and Time-Stained Rocks

CHAPTER FIVE The Legacy of Pout

CHAPTER SIX The Old Campaigner

CHAPTER SEVEN Buddha in a Toga

CHAPTER EIGHT A Little Warmer than Necessary

CHAPTER NINE Wild in Human Faith and Warm in Human Feeling

CHAPTER TEN A Subject of Frequent Remark

CHAPTER ELEVEN Hiding Behind the Elgin Marbles

CHAPTER TWELVE Some Primitive Vigour

CHAPTER THIRTEEN New Observations and Discoveries

CHAPTER FOURTEEN An Idolatrous Affection

CHAPTER FIFTEEN The Stupendous Fabric of Nature

KEEP READING

Author’s Note To Third Edition

Sources and Bibliography

Index

Chronology 1765–1927

The Great Arc

India: A History

About the Publisher

1. Aurangzeb’s mosque above Panchganga.

2. James Prinsep with Hindu pandits, Sanskrit College, Benares.

3. The rock of Girnar.

4. The temples of Mahabalipuram.

5. Cave temples of western India.

6. The stupas of Sanchi.

7. The ruined temple of Boddh Gaya.

8. A Buddhist stupa railing at Mathura.

9. The Buddha.

10. A Boddhisattva.

11. The temple complex of Khajuraho.

12. Carving at Khajuraho.

13. The festival of Jagannath at Puri.

14. Colin Mackenzie at work.

15. Bishop Heber’s drawing of Amber palace.

16. Gwalior, the ‘Gibraltar of India’.

17. The Qutb mosque.

18. Shah Jehan’s Jama Masjid.

19. The tomb of Humayun in Delhi.

20. The Taj Mahal in Agra.

21. The Sanchi torso.

22. The wall paintings in the caves of Ajanta.

23. A scene depicting ‘The Temptation’ in Ajanta Cave.

24. Colonel James Tod. 25. Colonel Colin Mackenzie. 26. E. B. Havell. 27. Sir William Jones. 28. Lord Curzon. 29. B. H. Hodgson. 30. General Sir Alexander Cunningham. 31. Sir George Everest by William Tayler.

32. Mohenjo-daro Giri.

33. Seals from the Indus Valley civilization.

The author and publisher are grateful to the following for their kind permission to reproduce the above illustrations: the India Office Library, British Museum for nos. 1–5, 7, 11, 13–16, 19, 22, 25–30; the Victoria … Albert Museum for nos. 6, 9, 17, 18, 23 and 24; the British Museum for nos. 10 and 33; the Werner Forman Archive, London for no. 12; the British Architectural Library, RIBA for no. 20; the National Portrait Gallery no. 31; and the National Museum, New Delhi for no. 32. Illustration no. 8 is reproduced from Archaeological Survey of India, Report of a Tour in the Central Provinces Lower Gangetic Doab 1880–81 by Alexander Cunningham, Vol. XVII, Plate xxi.

Some day the whole story of British Indology will be told and that will assuredly make a glorious, fascinating and inspiring narrative.

A. J. Arberry, British Orientalists (1943)

Two hundred years ago India was the land of the fabulous and fantastic, the ‘Exotic East’. Travellers returned with tales of marble palaces with gilded domes, of kings who weighed themselves in gold, and of dusky maidens dripping with pearls and rubies. Before this sumptuous backdrop passed elephants, tigers and unicorns, snake charmers and sword swallowers, pedlars of reincarnation and magic, long-haired ascetics on beds of nails, widows leaping into the pyre. It was like some glorious and glittering circus – spectacular, exciting, but a little unreal.

Now, in place of the circus, we have the museum. India is a supreme cultural experience. Instead of the rough and tumble of the big top, we have meditation and the subtle notes of the sitar. It is temples and tombs, erotic sculpture, forlorn palaces and miniature masterpieces. Hinduism is studied in deadly earnest; the ascetic no longer needs a bed of nails to ensure an audience. Even the elephants and tigers have become too important to be fun; they too must be carefully studied and preserved.

This dramatic change in attitude was principally brought about by a painstaking investigation of all things Indian. No subject people, no conquered land, was ever as exhaustively studied as was India during the period of British rule. It is this aspect of the British affair in India which forms the subject of this book.

The nineteenth century was the age of enquiry. It was perhaps inevitable that India should have its Darwin, its Livingstone and its Schliemann. There was also something in the paternalistic nature of British imperialism that attracted the scholar and the scientist. The men who discovered India came as amateurs; by profession they were soldiers and administrators. But they returned home as giants of scholarship.

And then, above all, there was India itself, exercising its own irresistible fascination. The more it was probed the greater became its antiquity, the more inexhaustible its variety, and the more inconceivable its subtleties. The pioneers of Indian studies, described in this book, rose to the challenge. ‘Man and Nature; whatever is performed by the one or produced by the other’ would be the field of their enquiries.

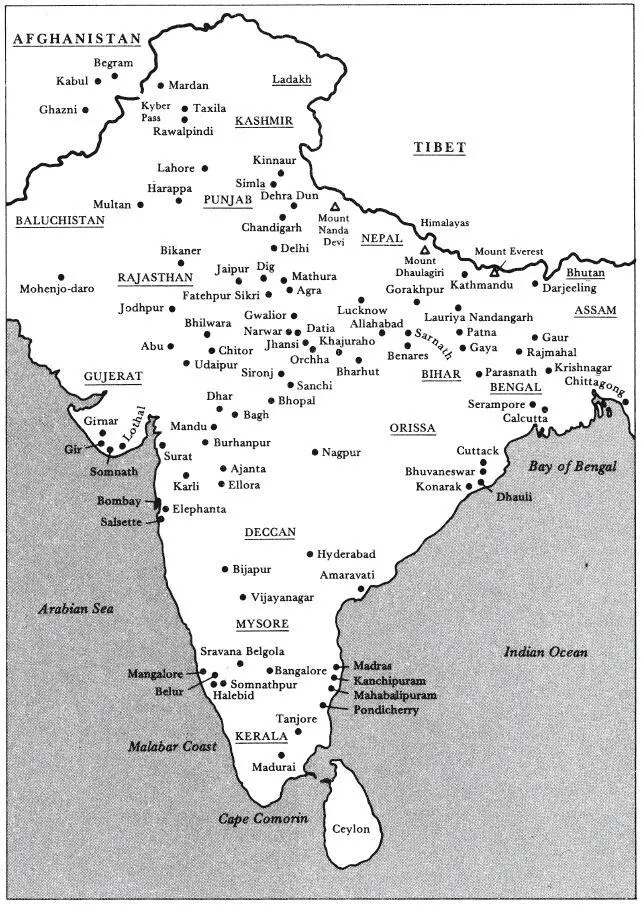

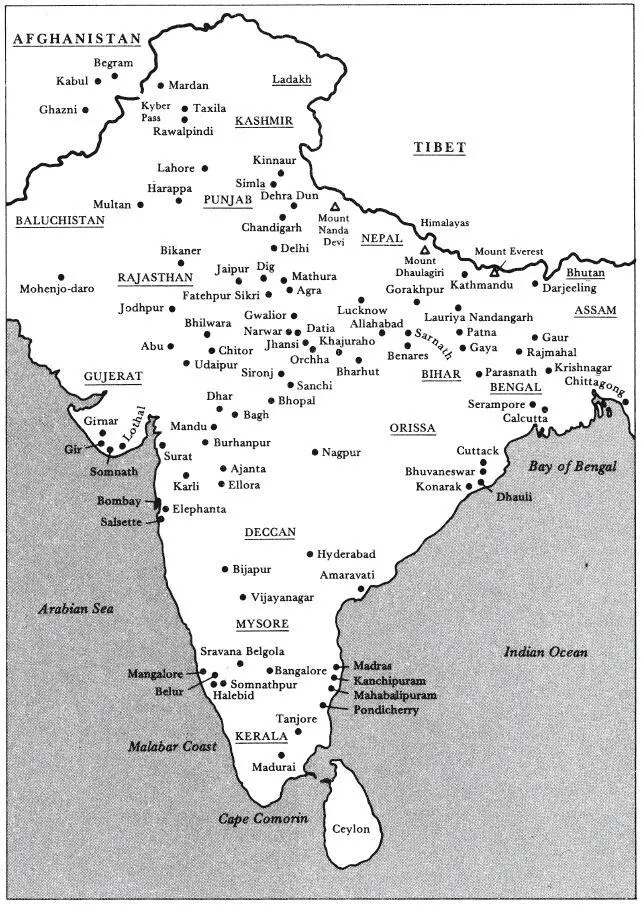

The results, even in an age of discoveries, were as sensational as the country and the scope of the undertaking. For a start, Indian history was pushed back two thousand years, roughly from the age of William the Conqueror to a millennium or so before that of Tutankhamun. In the process two great classical civilizations were discovered, and one of the richest literary traditions was revealed to the outside world. So were the origins of two of the world’s major religions. What Lord Curzon called ‘the greatest galaxy of monuments in the world’ was rescued from decay, classified and conserved. Ancient scripts were deciphered, dated and used to disentangle the history of kings and emperors. Coins and paintings by the hundred were discovered, and their significance charted. Western sensibilities struggled to come to terms with the discovery of erotic sculptures in places of worship. In the natural sciences one of the most exciting flora and fauna was studied and catalogued; so too was the incredibly rich human miscellany of racial, linguistic and religious groups. The entire sub-continent was surveyed and mapped; in the process the world’s highest mountains were measured. And so on. In short the modern image of India was pieced together.

Читать дальше