JOHN KEAY

MAD ABOUT

THE MEKONG

Exploration and Empirein South-East Asia

DEDICATION CONTENTS Cover Title Page Dedication Foreword An Indo-China Chronology 1 Apocalypse Then 2 Shuttle to Angkor 3 To the Falls 4 Unbuttoned in Bassac 5 Separate Ways 6 River Rivals 7 Hell-Bent for China 8 Heart of Darkness 9 Into the Light 10 Death in Yunnan Epilogue Acknowledgements By the Same Author A Short Bibliography Index About the Author Praise Copyright About the Publisher

FOR ALEXANDER

Cover

Title Page JOHN KEAY MAD ABOUT THE MEKONG Exploration and Empirein South-East Asia

Dedication DEDICATION CONTENTS Cover Title Page Dedication Foreword An Indo-China Chronology 1 Apocalypse Then 2 Shuttle to Angkor 3 To the Falls 4 Unbuttoned in Bassac 5 Separate Ways 6 River Rivals 7 Hell-Bent for China 8 Heart of Darkness 9 Into the Light 10 Death in Yunnan Epilogue Acknowledgements By the Same Author A Short Bibliography Index About the Author Praise Copyright About the Publisher FOR ALEXANDER

Foreword

An Indo-China Chronology

1 Apocalypse Then

2 Shuttle to Angkor

3 To the Falls

4 Unbuttoned in Bassac

5 Separate Ways

6 River Rivals

7 Hell-Bent for China

8 Heart of Darkness

9 Into the Light

10 Death in Yunnan

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

By the Same Author

A Short Bibliography

Index

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

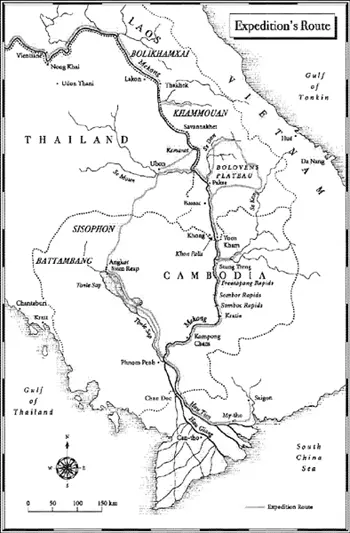

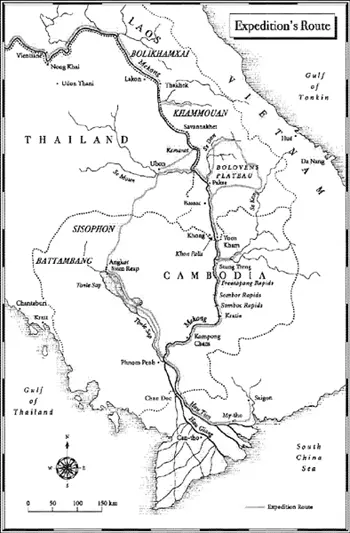

In the great age of exploration, while momentous expeditions in Africa were grabbing the English-language headlines, a French initiative through the heart of south-east Asia was arguably more ambitious than any of them. The Mekong Exploration Commission of 1866—68 outmarched David Livingstone and outmapped H.M. Stanley. It also outshone them in that display of sociological categorising, economic sleuthing and political effrontery that was expected of nineteenth-century explorers. In darkest Africa the British were feeling their way, but the French in tropical Asia unashamedly advertised their patriotic intentions, planted their flag and promoted their rule wherever they could. Empire-building was their business. An ‘empire of the Indies’, otherwise French Indo-China, would duly emerge as a direct outcome of the expedition.

The human cost of travel in the south-east Asian subcontinent was as high as in Africa, and the disappointments just as acute. Danger overtook the Mekong expedition within a week of its official departure; tragedy struck within a week of its effective conclusion. In between, as they clocked up the months and the kilometres in a marathon of survival, the explorers fought their way through the equatorial forests of Cambodia and Laos to climb from the badlands of remotest Burma onto blizzard-swept tundra along the China-Tibet border. Rarely was at least one of the six officers – and sometimes all of them – not delirious or incapacitated. Tigers barred their path, village maidens diverted their attentions, forbidden cities yielded up their secrets. The boats got smaller and the river more impetuous. They took to the jungle, riding on elephants, bullock carts and horses; mostly they just sloshed through the monsoons knee-deep in mud and festooned with leeches. If only as an epic of endurance, the story of the Mekong Exploration Commission dwarfs nearly all contemporary endeavours.

Yet – and hence this book – it is to most people unknown. Doudart de Lagrée, Francis Garnier and their companions are not household names. Any geographical features once called after them have long since been erased from the maps; and histories and anthologies of exploration habitually ignore them (my own included). One might suppose this to be an anglophone conceit. Had the Commission been British, London would now be graced with statues of the Mekong pioneers, streets would be named after them, and symposia convened for them. Their mistake, as Garnier himself wryly put it just before his premature death, lay in being born French.

Posthumous amends had, I presumed, been made in Paris, but it was during an encounter with the French ambassador in London that I first found a chance to confirm this. By way of something to say, I enquired how the Commission was commemorated in France. The ambassador looked blank. A charming and erudite diplomat, he evidently didn’t understand the question. I plied him with names, dates and places. He shook his head.

‘Never heard of them, I’m afraid.’

‘But that’s like a British ambassador saying he’s never heard of Dr Livingstone, or Scott of the Antarctic.’

‘Ah, but you don’t understand. In France we have a different attitude to the colonial past.’

A visit to Paris eventually bore this out. Except in the Bibliothèque Nationale and among the treasures poached from Angkor in the Musée Guimet, mention of the Commission brought nothing but Gallic shrugs. A friend whom I counted as an ardent supporter eventually confessed that even he only knew of the expedition because of my incessant prattling about it. Rue Garnier turned out to be named not for Francis Garnier; likewise the tomb in the Père Lachaise cemetery that is commonly awarded to him. Both pertain to some other Garnier. The short entry under ‘Garnier, Francis’ in the popular Larousse dictionary of biography contains only a sentence on the expedition; there is no entry at all for its leader, Doudart de Lagrée.

If one excludes the writings of its own personnel, scarcely any more accounts of the expedition exist in French than in English. The most recent and well researched (J.P. Gomane, 1994) appears never to have got beyond the limited circulation accorded to a typewritten thesis so scrunched into its binding as to be almost unopenable. The most ambitious and accessible reconstruction (Osborne, 1975) is by an Australian.

Celebrating dead exponents of a somewhat discredited profession seems to be an anglophonic obsession. The French ambassador, though far too diplomatic to say so, appeared to imply that while the British were today mired in nostalgia for their imperial past, the French were above such things and in healthy denial of their own colonial aberrations. Without going into the reasons for this – which may derive as much from present confidence as from past trauma – I felt encouraged. Here was a story that could usefully be retold.

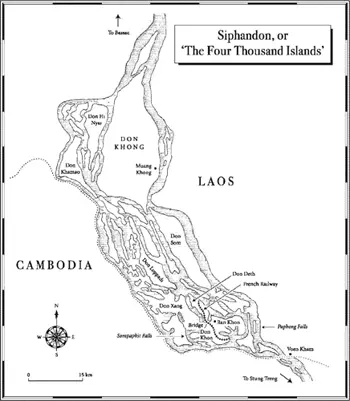

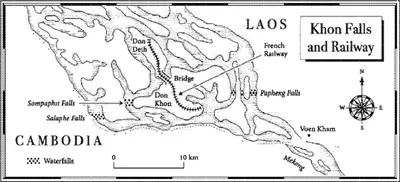

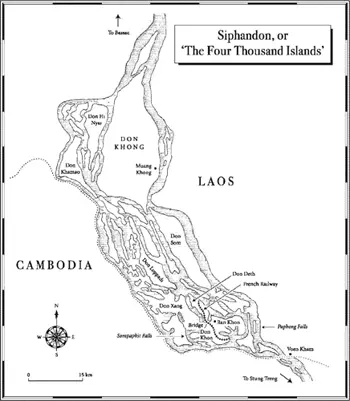

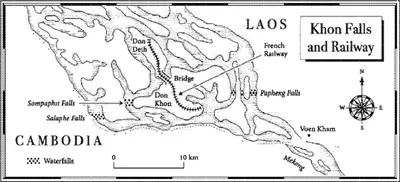

The history led to the geography. Intrigued by the expedition, I became enthralled by the river. For reasons that will emerge, the Mekong is quite unlike any of the world’s other great waterways. Far from inviting navigation it emphatically challenges it with an unrivalled repertoire of spectacular water features. As if not in themselves sufficiently discouraging, the expedition found these appalling physical difficulties compounded by political uncertainties. Colonial rule would fail to remove either, and for the past half-century ideological, bureaucratic and piratical obstructions have barred the river’s course more effectively than ever.

Читать дальше