Copyright Copyright About the Publisher

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollins Publishers 2001

Copyright © Sebastian Hope 2001

Maps © Jillian Luff 2001

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780002571159

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2013 ISBN: 9780007441099

Version: 2016-07-19

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication .

Dedication Dedication Maps Sarani’s Boat One Two Three Four Within the Tides Five Six Seven Eight Nine Keep Reading Index Acknowledgements Copyright About the Publisher

For Lisa

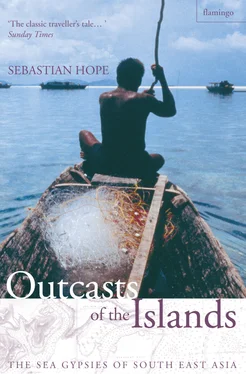

Cover

Title Page

Dedication Dedication Dedication Maps Sarani’s Boat One Two Three Four Within the Tides Five Six Seven Eight Nine Keep Reading Index Acknowledgements Copyright About the Publisher For Lisa

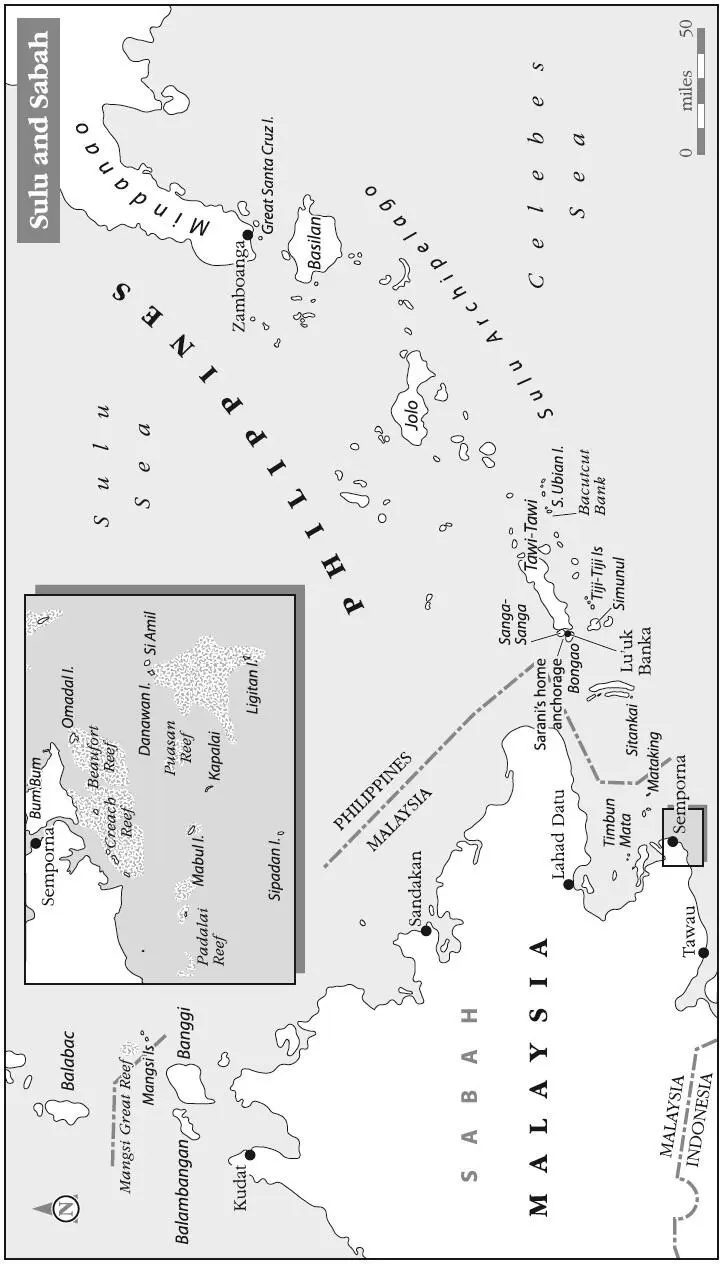

Maps Maps South East Asia East Coast of Sabah and the Sulu Archipelago West Coast of Thailand and the Mergui Archipelago (Myanmar) Singapore, the Riau-Lingga Archipelago and the East Coast of Sumatra South East Sulawesi

Sarani’s Boat SARANI’S BOAT

One

Two

Three

Four

Within the Tides

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Keep Reading

Index

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

South East Asia

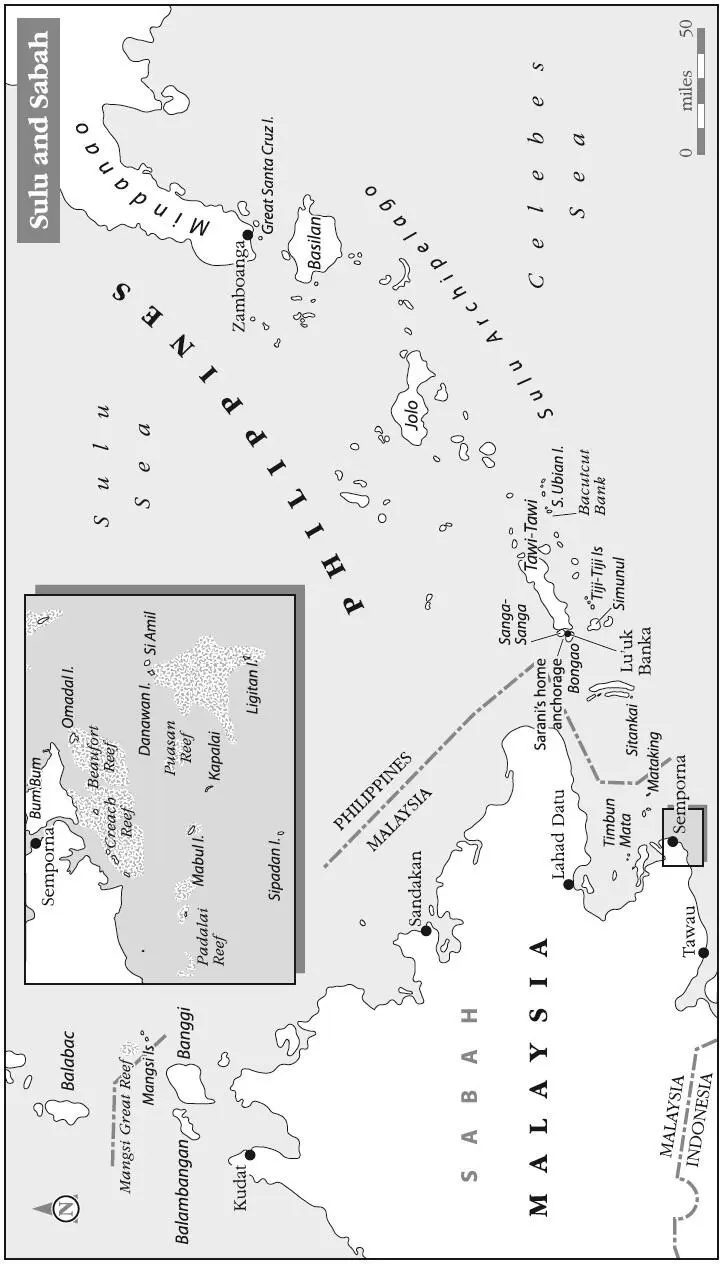

East Coast of Sabah and the Sulu Archipelago

West Coast of Thailand and the Mergui Archipelago (Myanmar)

Singapore, the Riau-Lingga Archipelago and the East Coast of Sumatra

South East Sulawesi

I know of no place in the world more conducive to introspection than a cheap hotel room in Asia. I had seen inside a score or so by the time I reached the Malaysia Lodge in Armenian Street. It was May and Madras waited for the monsoon. In the hotel’s dormitory, one night during a power cut, I saw Bartholomew’s map of South East Asia for the first time. I was eighteen.

In other hotel rooms I have puzzled over why that moment made such an impression on me. My first response was overwhelmingly aesthetic; can a serious person reasonably assert that his motive for first visiting a region stemmed from how it looked on a map? Compared to the sub-continental lump of India, so solid, so singular, the form of South East Asia was far more exciting – the rump of Indochina, the bird-necked peninsula, the shards of land enclosing a shallow sea, volcanoes strung across the equator on a fugitive arc. It was the islands especially that drew me. From the massive – Sumatra and Borneo and New Guinea – to the tiniest spots of green, I pored over their features by candlelight.

Thirteen years and hundreds of cheap hotel rooms later, in the spring of 1996, I was in the Malay Archipelago for the fourth time, studying my third copy of Bartholomew’s map spread out on a lumpy bed in Semporna. Its significations had changed for me; it had become a document that recorded part of my personal history.

The real discovery I made on my first trip to Indonesia was the language. I struggled with the alien scripts and elusive tones of the mainland, and progressed no further than ‘hello, how much, thank you’. I could ask, ‘where is …?’ in Urdu or Thai, but I would not understand the answer. I had become illiterate once more. Indonesian Malay was a gift in comparison. There are no tones and it uses Roman letters which are pronounced as they are written (apart from ‘ c ’ = ‘ch’). That was not the end of the good news. There are no tenses. The verbs do not conjugate. The nouns do not decline. There are neither genders nor agreements. Plural nouns, where the context is ambiguous or the number indefinite, are formed by reduplication of the singular. There were signs of more complex grammar lurking in the use of a number of prefixes and suffixes, but for a beginner the rewards are almost instant. Learn the words for ‘what’ ( apa ), ‘to want’ ( mau ) and ‘to drink’ ( minum ), say them one after another – apa mau minum? – and wonder at the unnecessary grammar and syntax English requires to ask the same question, ‘What do you want to drink?’ In six weeks I had learned enough of the language to make me want to learn more. Approximately 250 million people speak Malay.

By the time of my third visit to Indonesia my Malay was competent. I had become very interested in the country’s tribal peoples after a journey to Siberut Island off the west coast of Sumatra. It is an island some seventy miles long and thirty-five miles wide, covered in the main by rainforest. In the company of a trader in scented wood (who spoke no English) I crossed the island from east to west on foot and by dug-out canoe, stopping at the long houses of the Mentawai clans, a tribe of animist hunter-gatherers. I was entranced by their serene self-sufficiency and their harmonious relationship with the jungle.

On this third visit, I tried to repeat the experience in Sulawesi, where I met disappointment and the Wana people, slash-and-burn farmers who are turning a national park into a patch of weeds. I travelled with the park’s sole warden, Iksan, who was as despondent as I. We were glad to leave the Morowali Reserve, returning to Kolonodale the day before ‘Idu’l-Fitri, the Muslim feast at the end of Ramadan. Despite the fact that neither of us was Muslim we were invited to take part in the celebrations, making a tour of the town with a group of men and being invited to eat in every home. By the time we came to the water village, the houses built on stilts out over the shallows, I wondered how I could eat another thing. We were offered tea and cake in a spacious house made of milled timber belonging to a Bajo family.

I had heard of the Bajo people before, a tribe of semi-nomadic boat-dwelling fishermen to be found in the eastern archipelago. Their name even appeared on the map; the principal port of western Flores is called Labuanbajo, ‘Harbour of the Bajo’. It did not surprise me to find members of the group living in a house in Kolonodale – the Indonesian government has long pursued a policy of settling its traditionally itinerant peoples – but the head of the family told me that he had been born on a boat, and that he had relatives who still pursued the Sea Gypsy way of life. To hear that there were people who practised nomadic hunting and gathering on the sea not far from where I was sitting, refusing more cake, excited an instant desire in me to find these people, to travel with them. I started planning my next visit to the islands before I had even left.

Читать дальше