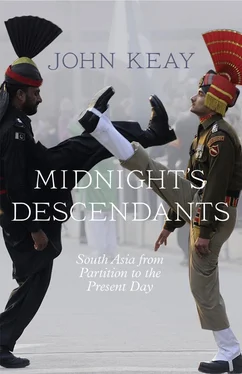

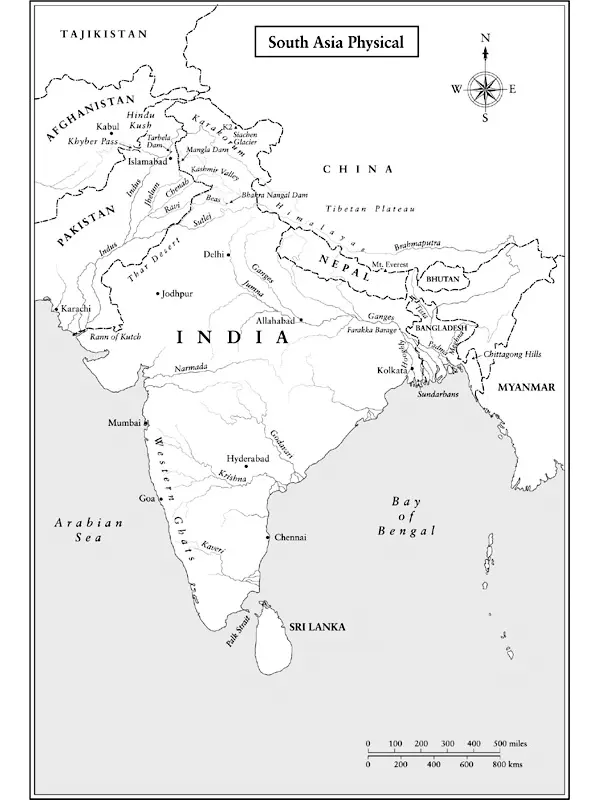

1. South Asia – physical

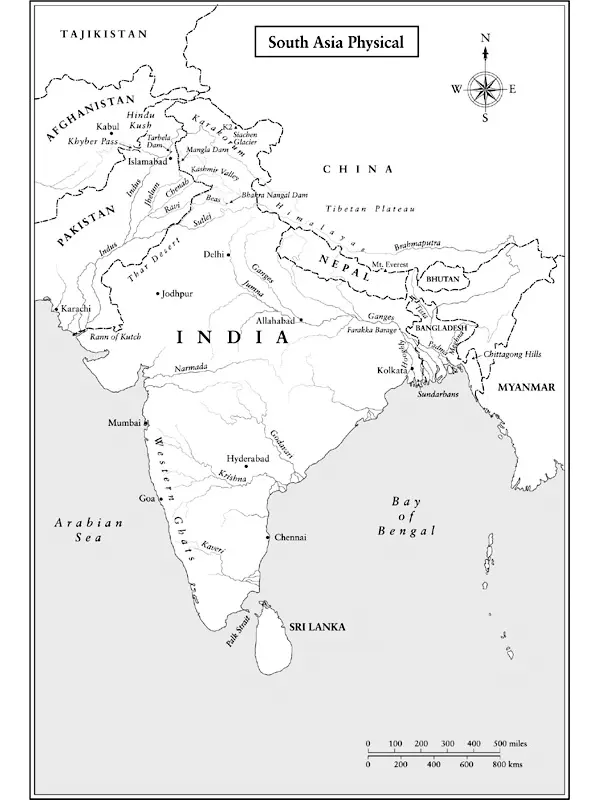

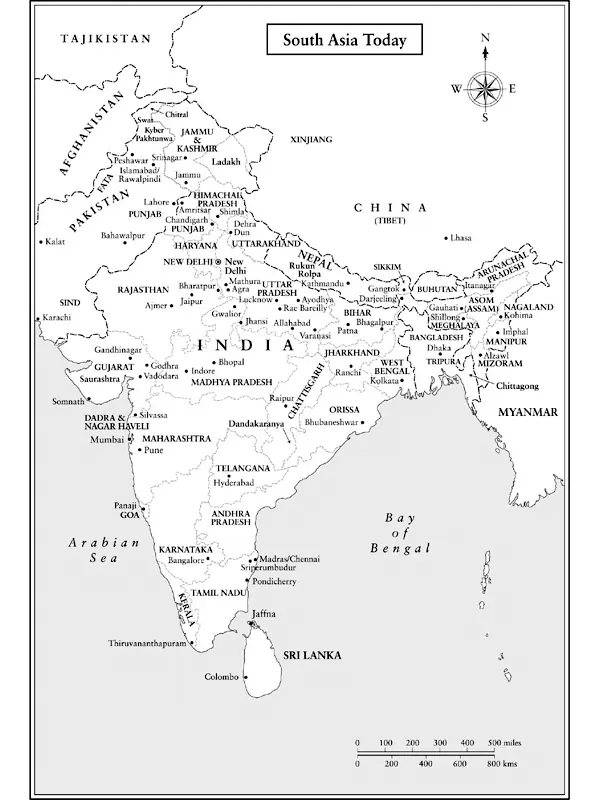

2. South Asia today

3. British India and the Princely States in 1947

4. North-East India and Bangladesh

5. Kashmir and Punjab

6. Political succession in South Asia, 1947–2014

I was six years old in 1947 when what was then British India won its independence. I vaguely recall the pomp and ceremony of the Delhi celebrations as filmed for Pathé News but have no recollection of seeing any coverage of the horrors of the Great Partition that followed. Pakistan I came across only in the classroom; it was not till nineteen years after Independence that I first visited what is now called South Asia.

Midnight’s Descendants is nevertheless a contemporary history. It spans my lifetime and has revived as many memories as questions. Since that first visit in 1966 I have been returning almost annually – as a journalist, documentary-maker, lecturer, writer of many books and taker of many holidays. In the process I have learned enough to know just how presumptuous this book is.

Contemporary history is itself fraught with pitfalls. It is, of course, a contradiction in terms: by definition, what is contemporary can’t be history. No record of the current can aspire to the detachment expected when writing of the past. Memory proves dangerously unreliable; impressions muddy the facts. A ready-made consensus does not exist in respect of many crucial developments, and access to the documentation on which later histories may be based is still embargoed. This book will probably be challenged and will certainly be superseded.

So why write it? The answer is simply that – both despite Partition and because of it – South Asia remains as distinct and crisis-prone a global entity as the Middle East (or ‘West Asia’, to South Asians). With a population greater than China’s, it is already the world’s largest market, and it may well host the world’s next superpower. In the past sixty-five years it has also staged at least five nasty wars and has more than once taken the world to the brink of nuclear conflagration. Yet its problems remain poorly understood, and its influence easily underrated. Studies of the region as a whole are surprisingly few. Visa restrictions limit travel and inhibit mutual exchange, much as prejudice limits mutual understanding. The outsider has a slight advantage here, which is my excuse for undertaking the book.

Over the years literally hundreds of friends and contacts have contributed to what follows. It would be invidious to attempt to list them; but one and all, I thank them. Sam Miller in Delhi and Philip Bowring in Hong Kong kindly read an early draft of the book. For their comments and encouragement I am enormously grateful, and I have enjoyed returning the compliment in respect of their own books. More immediately I want to record my debt to editors Lara Heimert and Sue Warga at Basic Books and Robert Lacey and Martin Redfern at William Collins. This is not by way of an authorial convention. Creative editors are a rare breed; so are patient ones. I have been blessed with four of the finest and most forbearing, and I thank them all most sincerely. For her still greater patience and unstinting support, and for her love, I am indebted to Amanda. But in her case thanks would be inappropriate and hopelessly inadequate. So I say no more.

John Keay

Argyll, 2013

Approaching Bengal from opposite directions, the Ganges and the Brahmaputra shy away from a head-on collision and veer south, their braided channels fraying and criss-crossing in a tangle of waterways that rob the parent rivers of their identities. Long before reaching the sea the Ganges has split into the Hooghly and the Pabna, among others, and the Brahmaputra into the Padma and the Meghna. Known as ‘distributaries’, these sub-rivers then fork some more, creating a maze of broad brown bayous whose combined seaward meanderings define the area known as the Sundarbans. Here, in the world’s largest estuarine wilderness, expanses of glossy mangrove and thick muddy water cover an area as big as Belgium. Islands are indistinguishable from mainland; promising channels expire in stagnant creeks. In the several designated wildlife sanctuaries, amphibious adaptation proves the key to survival. Crocodiles loll along the tideline close-packed like sunbathers. Mudhoppers gawp and glisten in the slime and the local tigers swim as readily as they prowl.

With roads a rarity, the best way to get around the Sundarbans is by boat, perhaps with a bike aboard for excursions on terra firma . A guide is essential, the trails being few and the landmarks fewer. The rivers tug one way, the incoming tide another. Neither is consistent: salt water comes down on the ebb, fresh water is backed up by the flow. The logic of the currents is as hard to fathom as that of the international border which here separates India and Bangladesh. Maps show the border as a confident line bisecting islands and slicing through peninsulas as it ricochets from side to side down the broad Raimangal waterway. Its trajectory provides the region with its one feature of human geography. But on the ground – where there is ground – the border is scarcely to be seen. Shifting mudbanks and encroaching mangroves are no more conducive to frontier formalities than they are to cartographic precision. Apportioning the Sundarbans between India and what was then part of Pakistan must have been like trying to carve the gravy.

A game warden announces a sighting: ‘Changeable hawk-eagle.’ He points to a large raptor lodged in a dead tree.

‘It’s a darker version of the one in peninsular India.’

The bird is rooted to its perch and motionless. It could be stuffed, its taloned feet nailed to the branch, except that every now and then it moves its head ever so slightly, as if troubled by indecision. Choosing the behaviour appropriate to its species is problematic for a changeable hawk-eagle. Should it quarter low over India’s chunk of the Sundarbans or soar high above Bangladesh’s? Is this a hawk day or an eagle day? Or just another changeable day? The options make for great uncertainty.

‘So is that bit over there India or Bangladesh?’ I’m asking. Nothing seems one thing or another in this gooey wilderness.

‘Oh, that’s India. Bangladesh is over there. See? But it should be India. Khulna, that whole district, should have come to India at Partition. It had a Hindu majority.’

Khulna was not awarded to India because Murshidabad, a Muslim district to the north of Calcutta that straddles the Hooghly river, was preferred by Delhi on the grounds of strategic contiguity and economic convenience. Eastern Pakistan, as Bangladesh then was, got Khulna by way of exchange. Hence mainly Muslim Murshidabad went to mainly Hindu India, and mainly Hindu Khulna went to mainly Muslim Pakistan. So much for the fundamental principle on which British India was divided by 1947’s Great Partition – that contiguous areas where Indian Muslims were in a majority were to constitute Pakistan, and that areas where they were not in a majority were to constitute the new India.

Dividing the subcontinent had itself been a compromise, and proved a heavy price to pay for independence. Flying in the face of fifty years’ struggle for a single India and of a shared cultural and historical awareness that stretched back centuries, it had been dictated by three recent developments: most Indian Muslims had come round to the idea of a Muslim homeland of their own; most Indian nationalists were insisting on a successor state that was strong enough to resist such demands; and the British were desperate for a fast-track exit. Adopted only as a last-minute expedient, Partition was widely regretted at the time. And by all who hold life, livelihood and peace to be dear, it has been rued ever since.

Читать дальше