This common thread of Latin, once the sound of Europe’s distinctive view of the world, is now a universal academic code, but also a thing of nostalgia. Latin, having been the no-nonsense, hectoring voice of Roman power, and then the soaring mood-music of the Catholic Church, has ended up being used above all to provide the scientific formulas that characterize every life-form on earth. But it is also a language of the heart: the foundation for romance—in all its senses—and a common cultural basis for Europe, the ultimate classic of education.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Latin came to be a schoolmaster’s language, passed on exclusively in the classroom by the inculcation—literally ‘trampling in’—of rules of grammar. (Not that this limited its prospects, or its utility in the wider world of power and propaganda: its influence was undiminished even a millennium later.) The popularity of favourite textbooks could be amazingly long-lasting: the record must be held by one of the first, Martianus Capella’s Marriage of Philology and Mercury , still being given to pupils twelve hundred years after it was first written in the fifth century AD, but honourable mention is due also to Alexander’s Doctrinale (279 editions all over Europe from the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries), and William Lily’s Short Introduction of Grammar , which was still regularly being used by English speakers everywhere two centuries after its first edition in 1511. By these standards, Benjamin H. Kennedy’s Latin Primer (first issued in 1866 but still in use today) is a mere latecomer. I was brought up on Kennedy, as was my father before me, and very likely my grandfather too (though I never asked him).

We were latecomers to Latin, then; but also at a turning point. The British Empire, which my father and grandfather had fought to defend, in India and in Africa, was dissolved into the Commonwealth while I was growing up in the 1960s. Right on cue, elementary Latin had ceased to be a requirement for entry to any British university by the end of the same decade. British imperialists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries had modelled themselves on the Romans, just as Spanish imperialists had in the sixteenth, and indeed American constitutionalists in the eighteenth. Europeans have in fact been enthralled by the memory of Latin ever since it ceased to be our working language. But in the 1960s the world was turning its back on it.

This Latin winter was sharp. Yet new and rather different institutions were already establishing themselves as the last of the European empires were passing to the vault of Orcus. The new world status of the United States of America after the Second World War was widely characterized with the Latin phrase Pax Americana ; here was a new imperial order, but one declaredly without colonies. Could the Roman model apply to it—whether of Empire or Church? And a Europe newly determined to abolish war among its nations has transformed itself into a European Union, choosing for itself a new Latin motto, In varietate concordia . In the twenty-first century, breakdowns in good governance in countries all over the world have tempted foreign-policy makers to reexamine the virtues of imperial-style intervention. The Roman model remains implicit, and that is one reason why Latin’s importance remains controversial to this day. It is time to examine the character of an empire, of a church, of a civilization, whose life was in Latin.

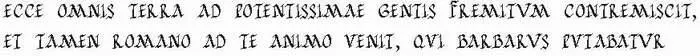

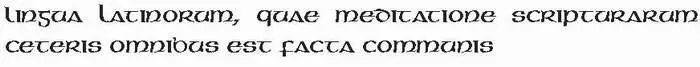

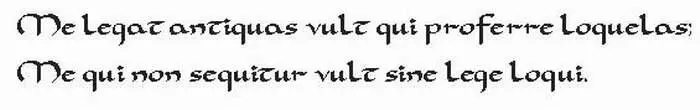

The language itself remained curiously unchanged throughout its long active career. Naevius’ and Bacon’s works are written in a common code, whose stable rules were transmitted intact through eighty generations of grammar school classes: contrast English, which has only existed at all for sixty generations, and which in its modern form has only lasted for twenty. What has changed has been in the handwriting, epigraphy and typefaces that have represented the eternal words on the page. The SQVARE CAPITALS *of the Roman Republic and Empire,

INMORTALES MORTALES SI FORET FAS FLERE, FLERENT DIVAE CAMENAE NAEVIVM POETAM.

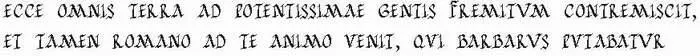

which are represented straightforwardly in the first nine chapters, yielded to a variety of rounder and more cursive scripts beginning in the fourth century. First there is rustic:

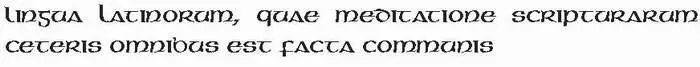

In the fifth century this was largely replaced by uncial, in the main a Christian innovation:

Then, in the late eighth century, Carolingian style took over, and this lasted for more than four centuries:

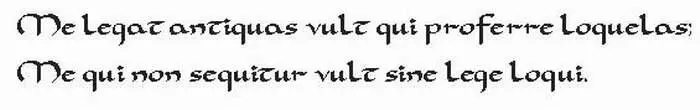

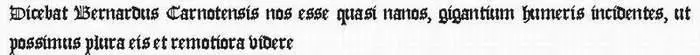

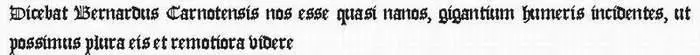

But in the thirteenth century this in turn was succeeded by the new Gothic, or Blackletter, style:

Gothic was still in place when the Germans of the fifteenth century invented the first typefaces for printing, and it became the model for them (e.g., for Gutenberg’s Bible). Italians, however, soon attempted to reinstate the old styles that they found in old (uncial and Carolingian) manuscripts and attributed to their beloved Ancients, inventing for the purpose the italic and Roman styles, which have remained characteristic of western European (and hence American) printing to this day.

An grammaticorum, quorum propositum videtur fuisse ut linguam latinam dedocerent? An denique rhetoricorum, qui ad hanc usque aetatem plurimi circumferebantur, nihil aliud docentes nisi gothice dicere?

Italice loquentem soli Itali intelligent; qui tantum Hispanice loquatur inter Germanos pro muto habebitur; Germanus inter Italos nutu ac manibus pro lingua uti cogetur; qui Gallico sermone peritissime ac scientissime utatur, ubi e Gallia exierit, saepe ultro irridebitur; qui Graece Latineque sciat, is, quocunque terrarum venerit, apud plerosque admirationi erit.

Aside from the square capitals of Rome’s Republican and Imperial language, this book systematically represents Latin in italics. Other languages that crop up—such as Etruscan, Greek, German, Hebrew, and the many varieties of Romance that have culminated in modern western European languages—are also set down in an italic transcription, but where a text is quoted in extenso at the head of a chapter, the authentic script is occasionally used.

Although plenty of Latin is cited in the text—and even more in the endnotes—the book does not aim to give you the rudiments of the language. For that—in default of a serious Latin course—you must consult Tore Janson’s Natural History of Latin , Harry Mount’s Amo, Amas, Amat … and all that , or indeed dear old Benjamin Kennedy himself. What this book aims to do, rather than to give a halting competence in the language, or re-create an echo of the experience in a grammar-school classroom, is to show what the career of Latin amounted to; and wherever possible, to infer the character, the respected ideal, that grew up within the tradition of the Latin language. This is partly an inspiration to us, but also a warning.

For although it claimed to be universal, Latin always indicated Rome as the fixed point of reference for its world. Latin knew no boundaries because it was looking inward, back towards the Eternal City. Perhaps the effort to understand a language and a civilization that were so polarized may reorient our own sense of direction.

Читать дальше

![Nicholas Timmins - The Five Giants [New Edition] - A Biography of the Welfare State](/books/701739/nicholas-timmins-the-five-giants-new-edition-a-thumb.webp)