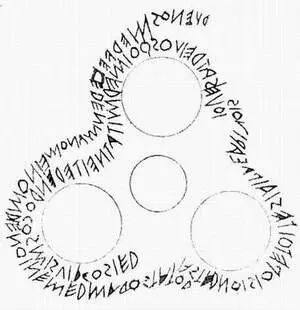

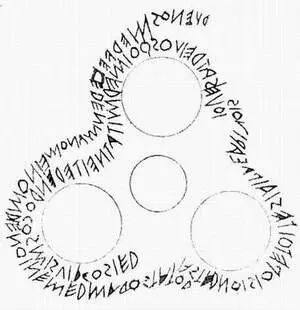

Consider for example the oldest substantial example, on the famous DVENOS ceramic, a tripartite, interconnecting vase rather reminiscent of a Wankel engine. Found in Rome in 1880, it is dated to the sixth or early fifth century BC, the same period as that early treaty.

The inscription is in three lines, which may be transcribed as

IOVESATDEIVOSQOIMEDMITATNEITEDENDOCOSMISVIRCOSIED

ASTEDNOISIOPETOITESIAIPAKARIVOIS

DVENOSMEDFECEDENMANOMEINOMDUENOINEMEDMALOSTATOD

and which are conjectured to mean

He who uses me to soften, swears by the gods.

In case a maiden should not be kind in your case,

but you wish her placated with delicacies for her favours.

A good man made me for a happy outcome.

Let no ill from me befall a good man. 7

This is unlikely to be fully correct—some of the vocabulary may simply be beyond our ken because the words died out—but even if it is, it presupposes that the words here must have changed massively over three centuries to become part of a language that Naevius would have recognized. Here is a reconstruction into classical Latin, with the necessary changes underlined:

iurat diuos qui per me mitigat.ni in te_comis virgo sietast [cibis] [fututioni] ei pacari vis.bonus me fecit in manum munus. bono_ne e me_malum stato

Virtually every word had changed its form, pronunciation, or at least its spelling between the sixth and the third centuries BC. This shows what rapid change for Latin occurred in these three centuries, comparable to what happened to English between the eleventh and the fourteenth centuries AD, when Anglo-Saxon (typified by the Beowulf poem), totally unintelligible to modern speakers, gave way to Middle English (typified by Chaucer’s writings), on the threshold of the modern language.

The inscription that circles the Duenos ceramic. Written in a highly archaic form of Latin, it appears to offer a love potion.

Yet (again like English), as reading and writing became more widespread, the pace of change in the language was to slow dramatically. Naevius’ poetry of the third century remained comprehensible to Cicero in the first, and indeed Plautus’ comedies, written in the early second century BC, were still being performed in the first century AD. Those plays are in fact written in a Latin close to the classical standard, canonized by Cicero and the Golden Age literature that followed him, a literary language that was simply not allowed to change after the first century BC, since every subsequent generation was taught not only to read it but to imitate it.

But why did this language, which only came to a painful self-awareness in the third century BC, go on to supplant not only all the other languages of Italy but almost all the other languages of western Europe as well? In the sixth century BC, a neutral observer could only have assumed that if Italy was destined to be unified, it would be under the Etruscans; and in the third century BC, Latin was still far less widely spoken than Oscan. Where did it all go right for Latin, and for Rome?

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

![Nicholas Timmins - The Five Giants [New Edition] - A Biography of the Welfare State](/books/701739/nicholas-timmins-the-five-giants-new-edition-a-thumb.webp)