Collins

Tracing Your Family History

Anthony Adolph

‘Who begot whom is a most amusing kind of hunting’Horace Walpole

For our friend’s daughter Kim Van Trier, who completed her journey from conception to birth in marginally less time and with considerably less fuss than the writing of this book, and for Scott Crowley, whose quiet support and encouragement throughout have been unfaltering.

Cover Page

Title Page

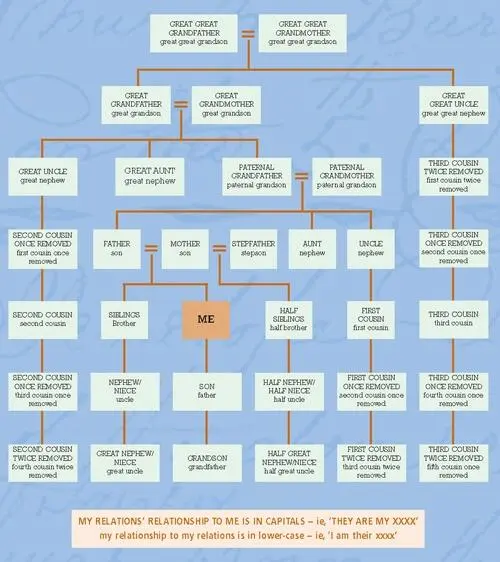

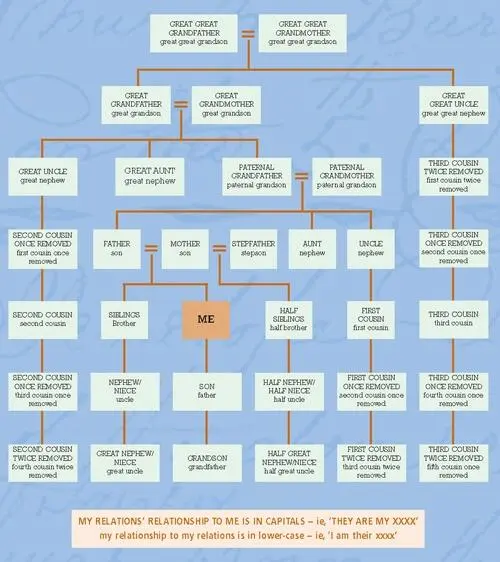

How We Are Related

Dedication

Introduction

PART ONE Getting Started

CHAPTER ONE Ask The Family

CHAPTER TWO Writing It All Down

CHAPTER THREE Ancestral Pictures

CHAPTER FOUR Before You Begin

PART TWO The Main Records

CHAPTER FIVE General Registration

CHAPTER SIX Censuses

CHAPTER SEVEN The Main Websites

CHAPTER EIGHT Directories & Almanacs

CHAPTER NINE Lives Less Ordinary

CHAPTER TEN Parish Records

CHAPTER ELEVEN Manorial Records

CHAPTER TWELVE Wills

CHAPTER THIRTEEN Gravestones & Memorials

PART THREE Taking It Further

CHAPTER FOURTEEN Newspapers & Magazines

CHAPTER FIFTEEN Land Records

CHAPTER SIXTEEN Slave Ancestry

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Maps & Local Histories

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN Records of Elections

CHAPTER NINETEEN The Parish Chest

CHAPTER TWENTY Hospitals & Workhouses

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE What People Did

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO Fighting Forbears

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE Tax & Other Financial Matters

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR Swearing Oaths

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE Legal Accounts

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX Education! Education! Education!

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN Immigration & Emigration

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT Religious Denominations In Britain

PART FOUR Broadening The Picture

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE Genetics

CHAPTER THIRTY What’s In A Name?

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE Royalty, Nobility & Landed Gentry

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO Heraldy

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE Psychics

Useful Addresses

Index

Acknowledgments

Copyright

About the Publisher

Long before there were computer programmers and engineers, blacksmiths or even farmers, our ancestors told each other stories of who they were and where they came from. Over time, as other subjects became more important (or at least seemed to be), our ancestral tales began to take a backburner, the older ones blurring into creation myths but the more recent ones remaining important to their tellers and listeners.

When memories started to be written down, one of the first things to be recorded were ancient genealogies, linking the living to their ancient roots. It is for that reason that we can trace the Queen’s ancestry back through the Saxon royal family to their mythological ancestor, the god Woden. Yet for most, the rise of written records heralded a gradual erosion of oral traditions and, in medieval England, memories tended to grow shorter in proportion to the proliferating rolls of vellum and parchment recording our forbears’ deeds, dues and misdemeanours. And then, just as it became apparent to our ancestors that they were losing touch with the past, it crossed people’s minds that these self-same documents, compiled for no better reason than to record land transfer, court cases or tax liability, could help us retrace our past and discover the identities of our forgotten forbears.

My great-great-grandparents, Albert Joseph Adolph and his wife Emily Lydia, née Watson. When I started my research, they were as far back as my grandfather’s memory stretched.

This, the act of tracing family roots through both remembered stories and written records, is genealogy, the subject that has preoccupied most of my life, first as an amateur and later as a professional ever since, as a child, I encountered the pedigrees of elves and hobbits at the back of The Lord of the Rings . And it has been my good fortune that the past few decades have been ones of exceptional growth in genealogy as a pastime across the world, from a minority interest with snobby overtones in the 1960s to a mainstream activity, contributing significantly to the tourist industry and constituting one of the principal uses of the internet. In recent decades, it has broken through, too, into the media.

The author presenting BBC1’s 2007 Gene Detectives with Melanie Sykes.

FAMILY HISTORY is enjoying an extraordinarily dynamic phase and much is changing. In the last few years, internet companies have realised the profits to be made by setting up pay-to-view websites, especially covering the two great building blocks of 19th-century family trees, General Registration and census records. The small amounts paid by users fund further indexing work, thus bringing yet more records within far easier reach of more people than ever before.

These sites have truly revolutionised searching. When I wrote the first edition of this book, I would only have sought people in the 1871 census (for example) if I had a precise address, or had no alternative choice. Now, I can search the entire 1871 census online in seconds. I would make one plea, though: if you are new to this, please don’t take these new developments for granted, or grumble at the relatively very small amounts of money being charged. You are at a vast advantage over genealogists in previous generations. Equally, however, pre-internet genealogists did have to get to grips with and understand how these records worked in far more detail, and this tended to make them very good researchers. So, having saved a lot of time thanks to the internet, why not use some of it to read the relevant chapters of this book, so that you can form a more rounded picture of how the original records were created, and where the originals may be found? This edition is as up-to-date as it can be – yet improvements in accessibility occur almost monthly. These are exciting times indeed.

The first year of this millennium saw two series appearing on national television, BBC 2’s Blood Ties and my own series, Extraordinary Ancestors , on Channel 4. These were followed by further series with which I have been privileged to be involved, particularly Living TV’s Antiques Ghostshow and Radio 4’s Meet the Descendants , which have continued to tell stories of genealogical investigation and discovery.

Читать дальше